April 3, 2024

Shepley Bulfinch Celebrates Its 150th Anniversary with Boston Exhibition

Throughout the firm’s history and numerous masthead changes, it has left an indelible mark on the American building scape. Not only have some of the country’s most visionary practitioners been in its employ, but the breadth of its portfolio—which now exceeds 5,400 projects—has informed how we design and engage with practically every campus, designed landscape, and building type to this day. A Legacy of Design Innovation: Shepley Bulfinch at 150 and Beyond reveals glimpses of those impacts, only in a modest storefront space probably better suited to a firm celebrating its 10-year anniversary. This is oddly fitting, given the firm’s reputation for substance over flare, but it leaves one wanting more. Still, they make do, and the history lessons on hand are palpable.

A biodegradable, thermoplastic model of Boston’s famed 13-story Ames Building (1891), the city’s first skyscraper, celebrates what was the firm’s first permanent home, which it occupied for 100 years. A Smithsonian-worthy ink drawing of a proposed but never realized plan for Albany’s Cathedral of All Saints, by Richardson’s hand, adorns a gallery wall.

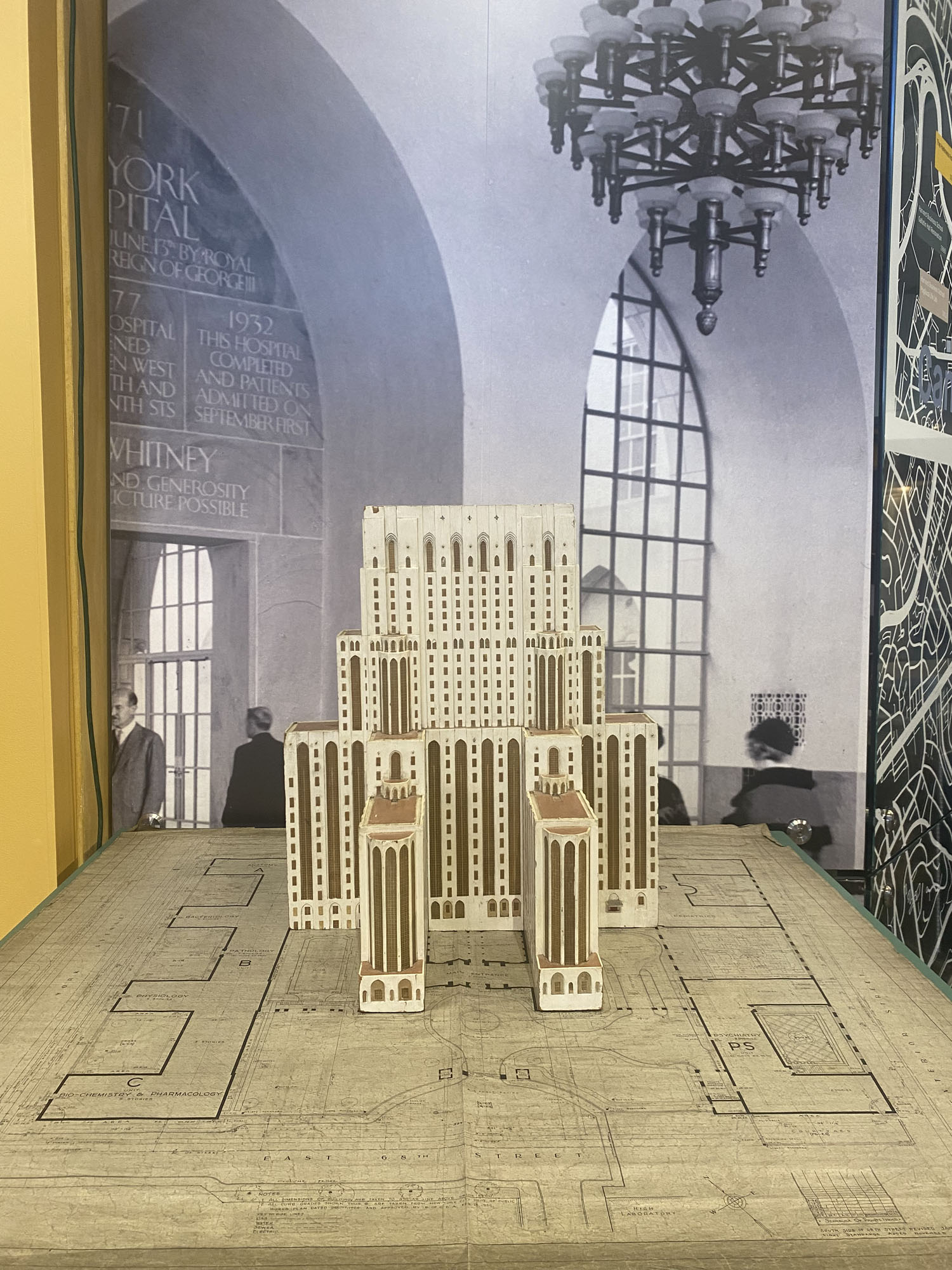

The most striking piece on hand, however, is an original basswood model of New York Hospital-Cornell Medical School complex, created in 1928 and sitting atop its original paint-on-linen plot plan. Arguably one of the world’s most consequential hospital designs, the building’s high ceilings, arched cathedral windows, glazed white exterior, interior courtyard, and flexible layout represent important forerunners to modern-day passive design strategies. Dozens of subsequent additions, all led by Shepley Bulfinch, have rendered the vast complex into a Tetris board mid-game, but the original structure’s continued appeal is a testament to its designer’s long-term thinking.

“Medical technology changes and people’s needs change. The world is always going to change,” says CEO Angela Watson, who joined the firm as a designer 21 years ago. “When we think about renovating and not tearing down, you can only do that if you have the capacity in that building to change.”

Watson’s colleague Luke Voiland, Shepley Bulfinch’s EVP of practice strategy, credits the firm’s longevity to its leaders’ approach to client and community engagement, and related efforts to nurture long-term thinking. “You can’t just find the most powerful person in the room and do what they want. That’s not going to produce good architecture,” he says. “It’s better when there’s complexity.” That sentiment is on display at McCormick, as is the firm’s capacity to evolve and modernize, with a particular focus on the healthcare and higher ed sectors. Models and drawings of more contemporary works share gallery space with historical examples, including an eye-catching early sketch by Watson of Ringling College of Art and Design’s Alfred R. Goldstein Library, a project that embodies an innovative take on the Sarasota Modern style.

Old roots can be a hindrance, but in Shepley Bulfinch’s case, they’re a ladder. Incidentally, one of those roots can be traced back to the country’s earliest days (engineer Francis V. Bulfinch, who became a partner in 1924, is a descendant of Charles Bulfinch, widely considered the first American-born professional architect). Beyond that, the firm has also made historical strides as a truly progressive enterprise, with many women at the helm for decades, including but not limited to its previous CEO Carole Wedge, and now Watson. In Watson’s estimation, success and equity are intertwined.

“It was really about creating this foundation, giving opportunities to women to lead, to have broad engagement with clients, to practice taking that feedback and turning it into design,” Watson says. “Now, we are basically at this equilibrium, which is amazing. We’re in stage two.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

Framery’s Smart Pods Prioritize Sustainability and Employee Wellness

Discover the Finnish brand’s latest innovation, the Smart Office Pod Collection.

Projects

WholeTrees Brings Structural Round Timber to the Children’s Museum of Eau Claire

the Children’s Museum of Eau Claire makes use of a new carbon-smart structural round timber (SRT) by Madison, Wisconsinbased timber products company WholeTrees Structures.

Projects

The Healthy Transformation of a Los Angeles Warehouse

Architecture firm Patterns turns a 1940s building into a senior care facility, resisting the car centricity of the area.