January 8, 2014

A Tale of Two Agendas: Evaluating Bloomberg’s Impact on New York

An event featuring New York’s new mayor has our columnist pining, unexpectedly, for the old one.

The Transition Tent, at Canal Street and Sixth Avenue, housed panels and discussions about the state of post-Bloomberg New York.

I was among the 73 percent of New York City voters who chose Bill de Blasio for mayor in the recent general election. I also voted with the 40 percent of voters who supported him in the primaries, when he walloped City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, the woman who was long regarded as the front-runner and Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s anointed one. Quinn, it appeared, was undone by a wholesale rejection of the development-friendly billionaire’s playground that New York had become under Bloomberg. I was part of that backlash.

After the election, this groundswell of left-leaning populist sentiment coalesced temporarily in a structure known as the “Talking Transition” tent. Erected on a long-vacant site at the corner of Canal Street and Sixth Avenue, the big tent was paid for by a group of donors, including liberal magnate George Soros. I spent one November afternoon there and, much to my surprise, found myself feeling nostalgic for the Bloomberg years.

Not that I’d been a steadfast supporter of the outgoing mayor; I voted for him once, in 2009, when he ran for a term-limits-busting third term. I’d had a come-to-Mike moment in 2007 when the mayor debuted PlaNYC 2030, his blueprint for a “greener, greater New York.” He stood on stage at the Regional Plan Association’s annual summit promising more transit-oriented development, sophisticated energy conservation methods, and lots of green power. Suddenly, the plutocratic mayor was talking to me. At that same event, he introduced his new transportation commissioner, Janette Sadik-Khan, a visionary who soon began reapportioning pavement, giving more of it to bicyclists, pedestrians, and those who just wanted to hang out in the little public plazas that were springing up all over town on what had previously been car-covered blacktop.

While I’d been slow to embrace Bloomberg, I did admire some of his hires. David Burney, an architect whom he’d appointed as commissioner of the Department of Design and Construction (DDC), implemented a program that awarded contracts to smaller, higher caliber architecture firms and vastly improved the quality of new public buildings. The same agency recently kicked off Built NYC, a program to equip new city buildings with furniture and fixtures by New York designers—a smart move in a city where the number of design jobs continues to grow. As the Center for an Urban Future (CUF) pointed out in its 2011 report “Growth by Design,” the number of design sector jobs grew by 75 percent from 2000 to 2009. And, as CUF research director David Giles recently told me, “Manufacturing employment in Brooklyn increased a tiny bit last year…for the first time in decades.” I would argue that the blurring of the line between designing things and producing them has something to do with that uptick, with programs like the DDC’s actually helping to increase local fabricators’ payrolls.

Of course, de Blasio’s “tale of two cities” theme during the campaign was not empty rhetoric: Homelessness in the city is now at a record high of 64,060, up 13 percent from last year. At the same time, Crain’s New York Business reports an influx of “ultra high-net-worth investors.” The city is home to 8,025 individuals worth $30 million or more. But even as I saw my vote for de Blasio as a vote against the specter of a Central Park overshadowed (literally) by 90-story residential towers in which globe-trotting oligarchs could weekend now and then, I recognized that the Bloomberg administration had an unprecedented flair for urban design.

Design was never a priority for Rudolph Giuliani, who was always the fire-breather—fighting small battles to the death—and never a big vision guy. Design didn’t figure into David Dinkins’s agenda, either. Ed Koch invested billions of dollars into turning abandoned buildings into affordable housing and breathing life into derelict neighborhoods, but you’d have to go back to John Lindsay’s administration of the 1960s to find the kind of enthusiasm for big-ticket urban reinvention that practically defined the Bloomberg administration.

So there I was in the Talking Transition tent listening to the ebullient Reverend James Forbes deliver a sermon (complete with gospel singer) called “Oh, What a Beautiful City.” The reverend complained that New York was not on the list that comes up when you Google the phrase “world’s most beautiful cities.” He suggested, no surprise, that a more beautiful New York would be one where problems like hunger and homelessness were addressed effectively. “A beautiful New York City is a city dedicated to compassionate justice,” he declared.

My quandary? As much as I agreed with Reverend Forbes’s vision of the “beautiful city,” I couldn’t advocate a wholesale rejection of the Bloomberg years. As I listened to affordable housing activists explain why we needed to legalize basement apartments, I began to try and disentangle the good parts of the Bloomberg years from the bad ones. The extension of the 7 train (a good thing) was paid for by bonds that will be repaid by the massive Hudson Yards development (arguably a bad thing). The city’s investment in the High Line (great!) can be read as an investment in a tax-revenue-generating luxury real estate boom on Manhattan’s far west side (not so great). Could we have had the administration’s extraordinary sensitivity to urban design without its extraordinary sensitivity to developers? Can we have the beautiful city without the cash flow generated by the voracious one? Were Bloomberg’s best initiatives always paid for by his worst impulses?

Of course, de Blasio didn’t get elected on a platform of good design—who does?—but I don’t get the impression that the discipline appears on the new mayor’s short list, either. His transition team is reasonably diverse, including developers, activists, and arts administrators, but no one, as far as I can tell, from fields like urban planning or architecture. This is why the case needs to be made right now, loudly, that design isn’t a luxury. Architects don’t just design 90-story condos. Good, affordable housing of the sort the new mayor wants to build requires smarter, more strategic design than towers for billionaires. It’s not just that good design (logical street signs, intelligent websites, well-conceived waste treatment facilities) is something that makes the lives of New Yorkers, whatever their income level, better; the real point is: Design is something we make here. We need to regard it as an industry, something that creates skilled jobs and, to the extent that it feeds a re-emerging manufacturing sector—and, yes, the construction trades—creates blue-collar jobs, too.

Of course, de Blasio didn’t get elected on a platform of good design—who does?—but I don’t get the impression that the discipline appears on the new mayor’s short list, either. His transition team is reasonably diverse, including developers, activists, and arts administrators, but no one, as far as I can tell, from fields like urban planning or architecture. This is why the case needs to be made right now, loudly, that design isn’t a luxury. Architects don’t just design 90-story condos. Good, affordable housing of the sort the new mayor wants to build requires smarter, more strategic design than towers for billionaires. It’s not just that good design (logical street signs, intelligent websites, well-conceived waste treatment facilities) is something that makes the lives of New Yorkers, whatever their income level, better; the real point is: Design is something we make here. We need to regard it as an industry, something that creates skilled jobs and, to the extent that it feeds a re-emerging manufacturing sector—and, yes, the construction trades—creates blue-collar jobs, too.

Listening to Reverend Forbes, I couldn’t help but notice that he delivered his sermon at a lectern made from plastic milk crates—three or four of them stacked up and topped with a level plywood disc. There, in the tent, the milk crate emerged as a symbol—entirely unofficial—of the transition. Again, de Blasio’s team had nothing to do with making the tent. Rather, it had been configured by Production Glue, an events company, which had chosen to enclose much of the structure with clear sheeting instead of opaque white plastic so that it looked a bit like a low-rent version of Norman Foster’s glass Reichstag dome. “More openness. More possibility. Very, very exciting,” the mayor-elect enthused on his visit to the tent. (The clear plastic also allowed the afternoon sun to turn the tent into a sauna.)

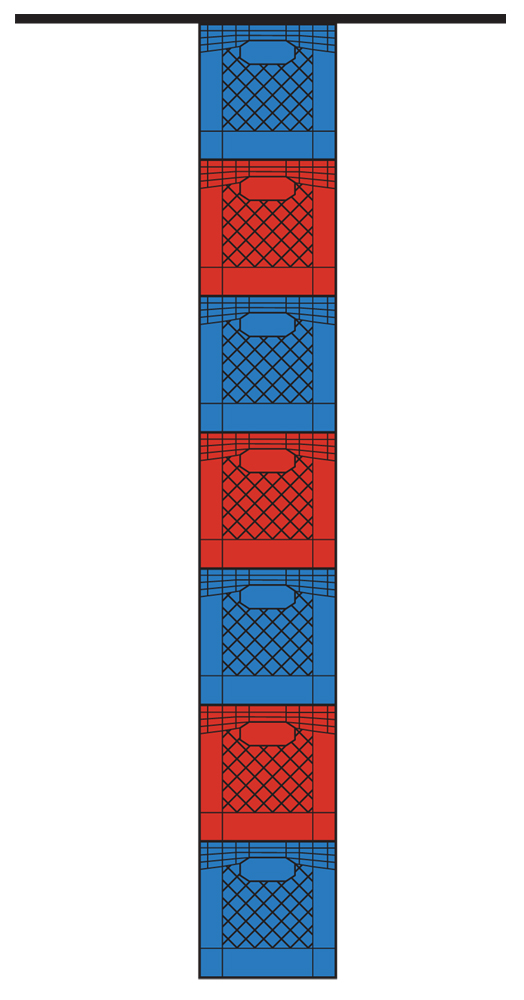

Inside the tent, the most conspicuous gesture of all was the milk crates. According to project designer Darren Norris, the “remit was to do something engaging but cost-effective.” Norris embraced the plastic milk crate in part because it evoked a “soap box aesthetic; some element of Speakers’ Corner.” The crates were available in cheerful primary colors. He used them to fashion giant sculptural signs, clever light fixtures (working with lighting designer Gregory Cohen), a bright mosaic wall behind the speakers in the tent’s largest meeting room, and the lecterns. The wholesale deployment of the crates was borderline brilliant because it highlighted a pragmatic, can-do approach to design—an attitude that the new administration would do well to understand and embrace.

While I can’t escape the conclusion that much of the great urban design that emerged during the Bloomberg years was the direct result of development schemes or rezoning efforts that have exacerbated the city’s economic disparities, I trust that there is a way to unlink skillful planning and placemaking from relentless gentrification.

In a report entitled “8 Ways to Grow New York’s Design Sector,” CUF made the point that design needs a champion in city government—a highly placed “chief creative officer” whose job it is to help grow and promote the industry. “When the city gets behind certain things, even just to amplify the message,” Giles says, “it can be a really big deal.” I can imagine a creative leader who would champion design as an economic development tool that benefits New Yorkers with a wide range of incomes and skill levels. This CCO could promote job growth while ensuring that the good Bloomberg, as exemplified by appointees like Burney and Sadik-Khan, doesn’t get lost in the shuffle.