November 7, 2016

New Exhibition Rediscovers the Overlooked Design Work of Pierre Chareau

A new exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York City rescues the French avant-garde architect and designer from obscurity.

A bust of Pierre Chareau created by artist Chana Orloff in 1921. Chareau and his wife assembled a noteworthy collection of Modern art, continuing to collect in exile in the United States.

Courtesy Ateliers Chana Orloff

If you’re a student of 20th-century architectural history, chances are you’ve come across Pierre Chareau’s Maison de Verre in Paris—a ground- breaking Machine Age house known for its innovative use of steel and glass that he created between 1928 and 1932 with the Dutch architect Bernard Bijvoet and the metalworker Louis Dalbet for Dr. Jean Dalsace, a prominent gynecologist at the time (Brigitte Bardot was later one of his patients.) With the exception of this masterpiece, Chareau’s work has remained in obscurity since his death.

Now, a groundbreaking exhibition, Pierre Chareau: Modern Architecture and Design, at the Jewish Museum in New York (on view until March 26, 2017) hopes to change that, examining the work of this avant-garde architect and designer who fled Europe at the start of World War II and attempted to rebuild his career while in exile in New York during the 1940s. It includes his interiors and architecture, innovative streamlined furniture (which was crafted with state-of-the-art movable parts), designs for film, and artworks that he once owned.

Why an exhibition on this designer, who built only a handful of works in the United States—the most well-known being the artist Robert Motherwell’s studio in East Hampton, New York, which was demolished in 1985? “To date, only two museums have had a show of Chareau’s work: the Centre Pompidou 23 years ago and two years ago the Panasonic Shiodome Museum,” says curator Esther da Costa Meyer, who is also a professor of modern architectural history at Princeton University. “It is high time we introduce him to the American public, all the more since Chareau fled to New York to escape German occupation and Nazi persecution in France, and died here ten years later.”

This exhibition presents Chareau’s career in a wider cultural context and includes aspects of his life that have not been explored before, such as his relationships with contemporary artists and the crucial importance of his wife, Dollie, to his work. “The Chareaus were avid collectors—within their means—and Chareau often incorporated modern art in his displays,” says da Costa Meyer, who worked on the exhibition for three years. “We have identified key works from their collection, which they were forced to sell in exile, and they will be displayed together again for the first time since they were sold by the couple.”

In interwar Paris, many champions of Modernism were French Jews who played a prominent role in cultural life as patrons, critics, artists, and writers. Chareau and his wife, who had Sephardic roots, and most of his clients were very much a part of this world. “The fate of this Jewish community under the Nazis is a central part of this story,” says da Costa Meyer, “as is tracing his extant furniture, some of which was confiscated by the Nazis.”

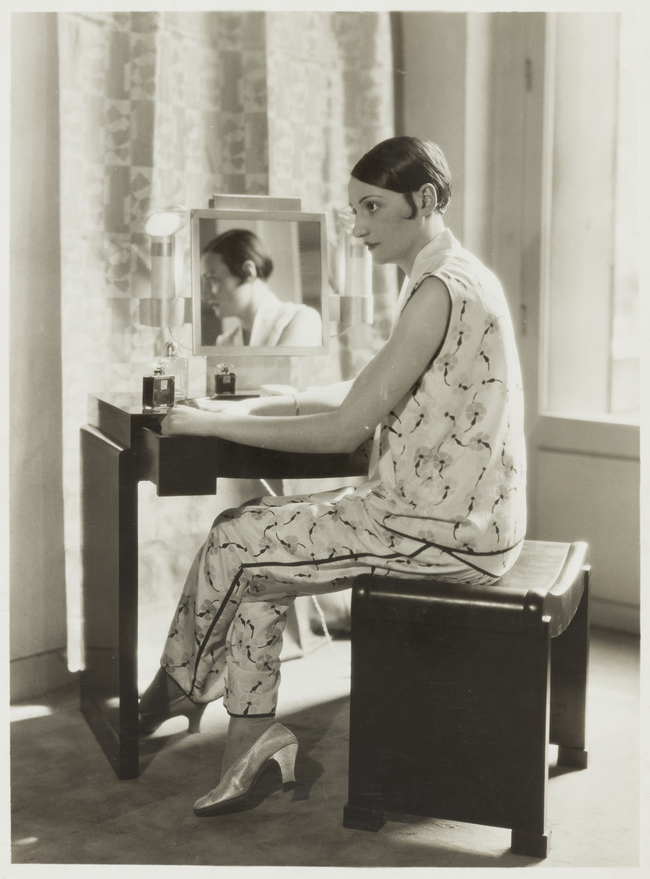

Chareau worked prolifically as a furniture designer throughout the late 1920s. He designed this mahogany dressing table, with an attached wrought-iron mirror and hinged cylindrical lamps, around 1926–27.

The model wears pajamas by acclaimed couturier Lucien Lelong.

Photograph by Therese Bonney, Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; Image Provided by Smithsonian Libraries

A telephone table, topped with the table version of his trademark lamp, La Petite Religieuse, designed around 1924.

Courtesy Collection of Audrey Friedman And Haim Manishevitz; Courtesy Press Office Cardarelli

A mahogany and sycamore dressing table, c. 1925–27. In 1925, Chareau was awarded a Légion d’Honneur for an installation at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, which cemented his reputation as an interior and furniture designer.

Courtesy Musee Natinoal D’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris