April 12, 2010

Letter from Baltimore: Container Corps

In her monthly “Letter from Baltimore,” Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson writes about architecture, culture, and urbanism in a city more often associated with violent crime than with good design. Click here to read her previous posts. For more by Dickinson, visit her blog, Urban Palimpsest. .In the winter of 2009, Ryan Patterson had an epiphany. The […]

In her monthly “Letter from Baltimore,” Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson writes about architecture, culture, and urbanism in a city more often associated with violent crime than with good design. Click here to read her previous posts. For more by Dickinson, visit her blog, Urban Palimpsest.

.

In the winter of 2009, Ryan Patterson had an epiphany. The community-arts coordinator of Parks & People, a Baltimore non-profit that greens neighborhoods and connects residents to the outdoors, was participating in a charrette when the conversation turned to new ways of delivering design services to underserved communities. Patterson wondered what would happen if you created a DIY design center of sorts, a mobile, modular structure that could become whatever the community needed. He imagined plunking an industrial shipping container into a neighborhood and creating a resource center. “The shipping container is a basic, modular thing that could be turned into any type of community center,” Patterson says. “It seemed a blank canvas that we could design on.”

A year and a half later, Patterson has taken this idea from concept to reality. He partnered with Barclay Elementary, an urban school that Parks & People has worked with over the years on—among other things—removing asphalt for green space and planting native habitat gardens. Through their Community Greening Resource Network, the non-profit creates tool sheds where community members can pay a modest $15 annual fee and get free plants, free seeds, and the ability to check out gardening tools. Patterson believed placing such a shed on the property of the elementary school would help cement the campus as a gathering spot while advancing the ongoing education of young students, who are learning about watersheds and native plants. “It’s a way to make the schoolyard a resource for the community around it,” he says. “It’s a park, it’s a place where people can congregate in positive ways, it’s an education tool.”

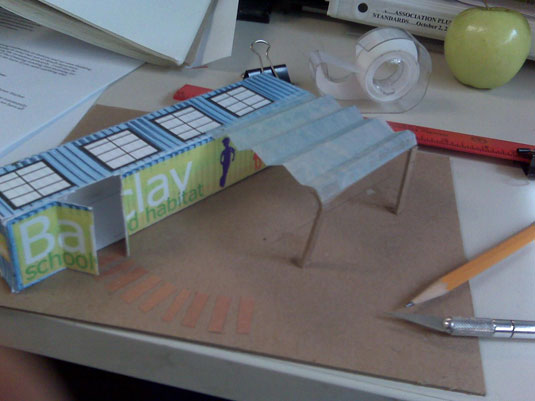

A model of the Barclay Elementary resource center

A model of the Barclay Elementary resource center

A used shipping container was delivered to the school in November for about $1,400, and Patterson set about working with the kids to design their new tool resource center. A mural with a green map of Baltimore will cover part of the exterior, while a newly fabricated butterfly roof will collect rainwater into barrels for on-site gardens. Students from grades 2–6 have worked on the project, which will be complete by the end of the school year.

The idea of bringing services directly to those who need it recently drove another Baltimore-based modular project. In December, architects from Hord Coplan Macht partnered with North Carolina-based Specvco (short for the Special Vehicles Company) to design mobile hospitals for underserved global communities. The design is currently in production drawing and is being shopped in countries like Morocco, Brazil, and Chile. One of these mobile hospitals would be composed of 58 trailers that combine to provide a fully operational, fully mobile 48-bed facility. The idea, says HCM principal Rolf Haarstad, is to deliver full health-care services and continuity of care to regions without hospital access. “We want these to become real health-care environments that would go beyond basic disaster relief,” he says.

Each trailer unit—specced to be fabricated from a high-end, thin composite steel—delivers different needs, from imaging and surgery to patient rooms, a cafeteria, and even a gift shop. The entire campus can be disassembled, relocated, and fully operational in a new location in 14 days. The units can either be tied into an existing energy system, or they can operate off-the-grid using solar energy and desalinating technology for water.

In addition to the full-hospital configuration, individual clinics composed of five trailer units—like a woman’s health clinic, or an imaging center—could be dispatched as needed. These stand-alone clinics are designed to be shut down in one location, mobilized, and re-opened in about three days. The hospital could also be used as a teaching hub, where Western medicine and training could be disseminated to local doctors. “These smaller units could go into different regions on a rotating basis, so patients in remote areas could see the same doctor,” Haarstad says.

The cost of this mobile hospital is a touch more than the $1,400 container employed by Patterson at Barclay Elementary. Haarstad estimates the full shebang could run between $50 and $100 million, comparable to the cost of building an actual hospital. But HCM believes the capacity to make it mobile is key. “It’s not that these are low-cost, it’s that they can be up and functioning in two weeks,” he says. “To be able to put this into areas where local labor isn’t available to build a hospital from scratch, where materials and resources may be scarce, is important.”

.

Previously: We wrote about Containers to Clinics, a Massachusetts nonprofit that’s developing a prototype portable health clinic constructed from industrial shipping containers.