May 12, 2014

Designing for the Outdoors in a Digital World

The latest installment of the Green Team series digs into 3-D modeling software and how it’s changed the practice of design.

In our last Green Team post, we described how designers often look to the past for inspiration. If we use this same lens to look back on the evolution of the design profession as a whole, what would we find? One immediate observation: we’ve gone digital. The last in our “Outdoors in a Digital World” series, this post takes a look at some ways in which designers use technology as a tool for design in the office setting.

What’s Your Process?

Has hand drawing become a nostalgic act? Certainly not. But, with the introduction of advanced computer programs for drafting, 3-D modeling, and photorealistic renderings, designers now have myriad options to enhance—but not replace—conventional hand-drafting. The renderings created for Pier 42, a Mathews Nielsen-designed project located in New York City, use an average of five separate computer programs to progress a rendering from a digital photo to the final product (see Image 1). Digital language is shaping design thinking in this tech savvy world, which we discuss in more detail below.

A computer-generated rendering showing the entry to Pier 42, both before (top) and after (below) digital manipulation.

Information Gathering

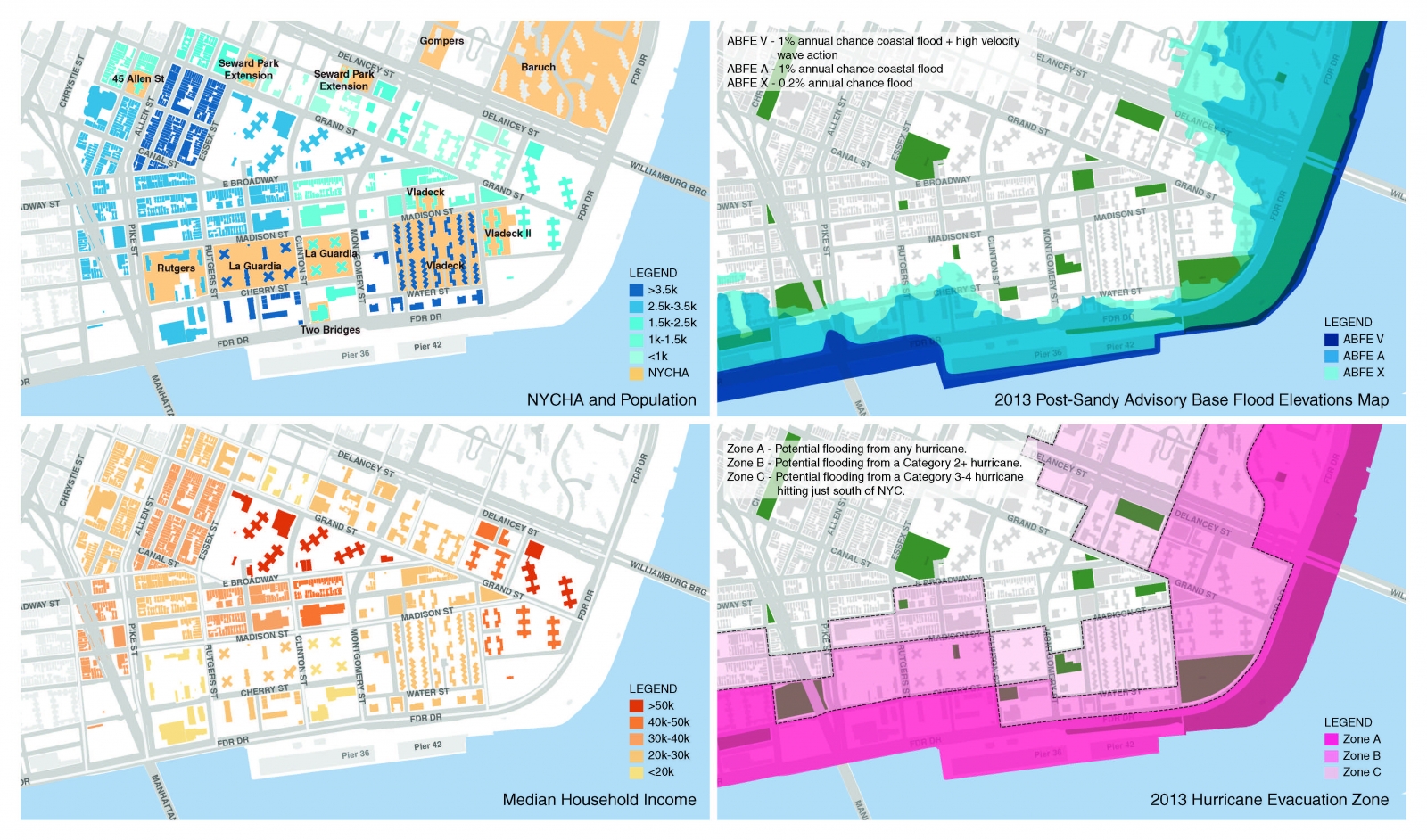

Now, more than ever, we have access to vast quantities of information, literally at our fingertips. Geographic Information System (GIS) data portals with extensive data sets are available for public use—from mapped data of subway entrances to mapped graffiti locations. As a part of the City of New York’s Open Data program, data specific to the context of Pier 42 was downloaded and examined by the design team at the neighborhood level. The team created a series of diagrams using this public information (shown in Image 2) to overlay existing mapping and data collection with big picture ideas as a method to inform and evaluate design decisions.

A series of diagrams created by overlaying mapped GIS data to identify neighborhood context and community trends. Shown are diagrams related to population, household income, flood elevations, and hurricane evacuation zones.

Using the available mapping and GIS data for other purposes, the design team employed environmental data to develop a preliminary three-dimensional model to frame the context of the site (shown in Image 3). To create the model, 2-D AutoCAD drawings of the site, as well as GIS data including building footprints and roof elevations, were imported into the Rhino, which allows the user to build, extrude, and join shapes and surfaces. Coupled with Grasshopper, a visual programming application that runs in conjunction with Rhino, the user can define parameters to code—or script—visual programming language specific to the project to build 3-D geometries. The Grasshopper definition built for Pier 42 involved the extraction of building height data to streamline the development of the model by extruding all building masses within a specified distance of the site. All at the click of a button (results shown in Image 3).

Put Away the Perspective Chart

Analysis through modeling isn’t new—physical models are still part of the office norm. Digital models, however, have started to streamline the design process with their ease of use and fast, accurate results that convey the complexities of a site beyond a simple 2-D drawing. Rhino, SketchUp, 3D StudioMax, Revit—digital software nomenclature is becoming commonplace. With the ability to consistently pan, zoom, and rotate views around drawn components, designers have amplified this unique tool in the workplace.

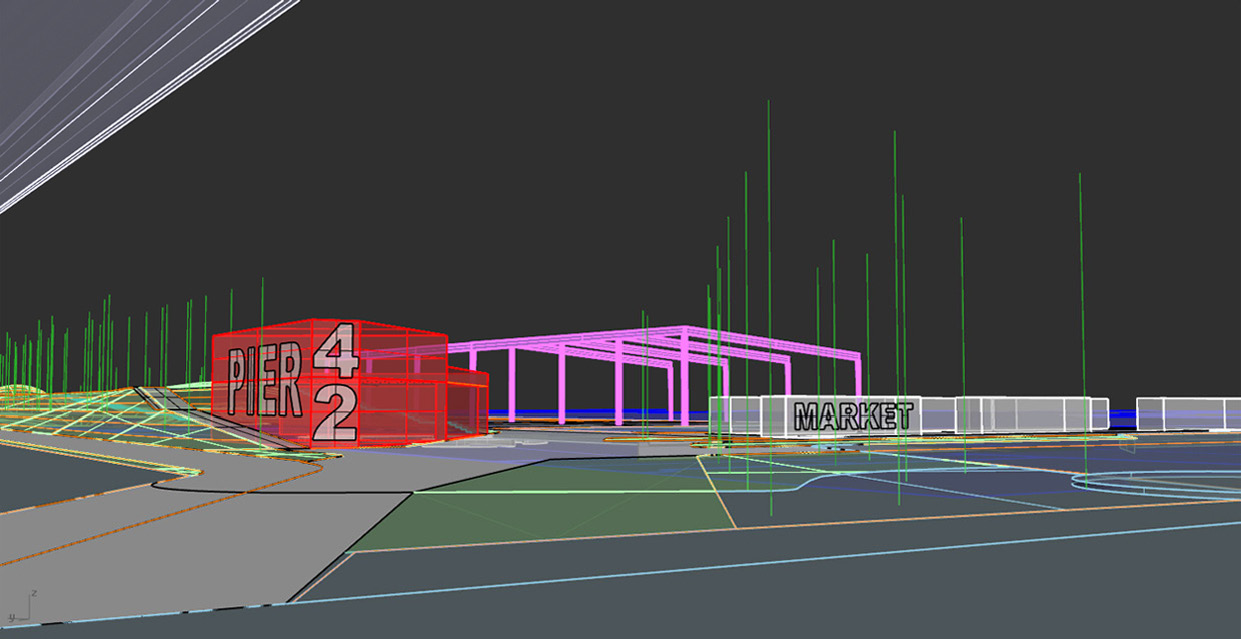

A snapshot of the Rhino model created for the entry at Pier 42 (shown in Image 4) demonstrates where surfaces can be changed and manipulated in precise ways. Modeling not only allows the designer to analyze spatial relationships, but it also becomes a tool for understanding topography, determining connections between built elements, highlighting views, and even understanding the importance of sun, shade, and shadow on designed components within a landscape. The ease of manipulation of these digital models is a testament to the rapid, changing pace of the design industry.

The start of a 3D Rhino model showing the entry relationship at Pier 42.

Design by Rendering

A 3-D model allows users to create the bones, or structure, of a photorealistic rendering. Many modeling programs are outfitted with built-in rendering capabilities that allow for simple rendering. This type of rendering is completed with VRay (shown in Image 5), a Rhino plug in that adds shadow, light, texture, and color to modeled elements with a touch of realism once exported into a flattened 2-D image. More refined rendering and detailing can be completed with 2-D programs such as Adobe Photoshop or Illustrator, where we landscape architects like to layer in trees, people, shadow and additional color and texture.

Rendering with VRay, showing textures and context of the existing and designed elements at Pier 42.

This digital discussion is by no means all inclusive of every application, modeling, or rendering program out there—that would require its own book! So, what’s next? Creating animations and fly-throughs of the models to give a true “on the ground” sense of place? Integrating Building Integrated Management (BIM) components like Revit into the landscape? 3-D printing of site plans and models? As I look over at the mish-mash of loose hand sketches, precedent photos, illustrator diagrams, and prints of Rhino snapshots strewn across my desk, the evolution is apparent: the opportunities for digital representation are ever growing, ever evolving. It just depends on how you choose to use them.

What programs do you like to use in the office? Please share your ideas here or connect with me on Twitter @LisaDuRussel. Join us next time when we will get back to our plant discussion, celebrating spring and the Power of Green.

Lisa DuRussel, RLA, ASLA, LEED AP is a Midwestern transplant, avid coffee drinker, soils enthusiast, and practicing landscape architect in New York City. Since receiving her BS and MLA from the University of Michigan, she has worked on numerous urban revitalization and cultural landscape projects in the New York and Chicago areas, including the Governors Island Park and Public Space project. Connect with her on Twitter @LisaDuRussel.

This is one in a series of Metropolis blogs written by members of Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects’ Green Team that focus on research as the groundswell of effective landscape design and implementation. Addressing the design challenges the Green Team encounters and how it resolves them, the series shares the team’s research in response to project constraints and questions that emerge, revealing their solutions. Along the way, the team will also share its knowledge about plants, geography, stormwater, sustainability, materials, and more.