October 14, 2008

More Than One Good Chair

How do the entrants in one furniture competition stack up?

Does sustainability change the face of design or merely its content? Can we be as smart about the way things look as we are about how they’re made?

This is the premise of the One Good Chair design competition, which I organized this past summer. The competition was informed by research for my forthcoming book, The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Design, which considers how form and image can enhance conservation and comfort at every scale of design, from products to communities. I expected to find many compelling examples of my topic in the furniture industry. I was wrong.

The furniture industry may be going green, but, like every other industry, it’s doing so almost exclusively through materials and methods-recycled content, sustainably harvested wood, low-toxin adhesives, dyes, and paints, etc. Appearance, however, is equally important: How something is shaped can have just as much-if not more-impact on its use of resources, its longevity, and its effects on health and well-being.

In my research I found little evidence that designers are greening the look and feel of design as much as its nuts and bolts. Then it occurred to me that staging a design competition would be an effective way to spur interest in the topic and solicit possible illustrations for the book. So I reached out to Susan Inglis of the Sustainable Furnishings Council, a newly established non-profit dedicated to promoting sustainable manufacturing practices. She embraced the idea and brought in Margaret Casey of the World Market Center, which sponsored the competition. Our media partner was Western Interiors and Design magazine.

We established a Web site and sent out a call for entries inviting designers everywhere to contribute their vision for a new kind of eco-chair, one that focuses first and foremost on form. The basic questions we asked entrants to address were these: What kind of shapes can minimize resources while maximizing comfort and enjoyment? How can design integrate ecology and ergonomics?

We had no idea what would come of this. In the end we received nearly 300 entries. The diversity of ideas ranged from the familiar (innumerable bent-ply chairs) to the shocking (trash bound together as a lounge mat) to the unclassifiable (a rendering of a computerized green blotch that displayed its energy statistics but offered no obvious place to sit down). But accompanying these were also many exceptional visions that stood out for their simple elegance and novel approach.

The jury-made up of Galen Cranz, UC Berkeley professor and author of The Chair: Rethinking Culture, Body and Design; Bill Dowell, director of research for Herman Miller; Jill Fehrenbacher, designer and founder of Inhabitat; Eric Pfeiffer, designer of the Mag Table and co-author of Bent Ply: The Art of Plywood Furniture; Susan S. Szenasy, editor in chief of Metropolis; Michael Wollaeger, editor in chief of Western Interior and Design, and myself-chose two winners and three runners-up, to represent the best of the broad range of entries.

RUNNERS-UP

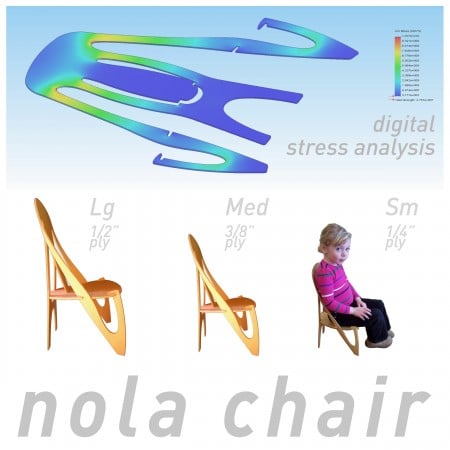

NOLA Chair

Robert Corser

Designed pro-bono to support post-Katrina rebuilding efforts among civic groups in New Orleans, Corser’s NOLA Chair blends new technology and traditional form-economy and stylization. A plywood adaptation of Art Nouveau imagery-appropriate for a city with a strong French history-it makes me fantasize about a possible collaboration between Hector Guimard and Charles and Rae Eames. Corser says he wanted to challenge familiar approaches to flat-pack furniture by using digital tools to create a pattern that could ship flat but be bent into its final form, holding together through its own internal stresses. The result costs about $40 in material, uses roughly half of a single plywood sheet, and increases shipping efficiency eight-fold. Some judges thought the design too visually complicated, and others felt it was not very “body conscious,” but most felt it was a novel concept.

Jigai

Moon Choi

Inspired by the adjustable tripod supports of traditional Korean bamboo carriers, the Jigai chair uses little material but offers lots of versatility. The simple bent-ply seat is held up by a metal rod fitted into slots on the back, so the height and angle can change, depending on the body or mood of the user. The designer, Moon Choi, was interested in maximizing comfort while minimizing resources: “The intersection of sustainability and sensuality is simplicity.” Jurors loved the basic concept, and for Galen Cranz, a body expert, Jigai’s simple flexibility made it her first choice: “Humans are designed for movement, which requires change and variety.” She also felt that Jigai’s image conveys an important message. “Didactically, this is an important chair because it signals to the viewer that change and choice are expected and therefore legitimate. The simple form of this chair is not only restful for the body, but also for the brain. This chair makes a significant cultural contribution to ‘body-conscious design.'” Other jurors, however, had doubts about the chair’s stability-would it hold up a person without falling over? This question led to the suggestion that future competitions could require a prototype to test functionality and comfort.

Duv-tal

Catherine Pena

This entry sparked quite a controversy among the judges. Some felt it was the most inventive idea of the bunch, and some thought it ignored the criteria of the competition. The author declares that she designed the Duv-tal “in response to America’s obsession with cars and the lack of support for public transportation systems.” Attached to lamp posts and telephone poles to avoid independent supports, the seat gives passengers not just a place to rest, she says, but also “a sense of authority and autonomy by providing an elevated vantage point-a position of honor.” A park bench meets a royal throne. Some judges loved the chair’s ability to be humble yet raise important socioeconomic questions. Jill Fehrenbacher’s praise was simpler: “As an 8-month pregnant lady, I heavily support more seating in urban public spaces.” Yet, some of us felt strongly that this chair in no way demonstrated the basic idea of the competition-the significance of form. Bus stops are aesthetically mundane, and Duv-tal-a gloried bleacher seat-doesn’t do much to improve that fact. However, its reliance on existing urban infrastructure does reveal the possibility of a close connection between products and communities. Place-based furniture, such as the Adirondacks chair or the Charleston joggling bench, is rare. If Duv-tal’s design were more memorable and uniquely tied to its setting, it could spur more interest in public transportation and become the chair equivalent of Guimard’s Paris Metro stops or the London double-decker bus.

WINNERS

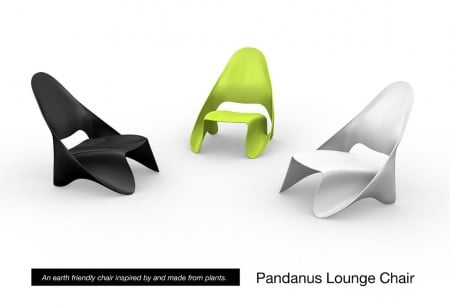

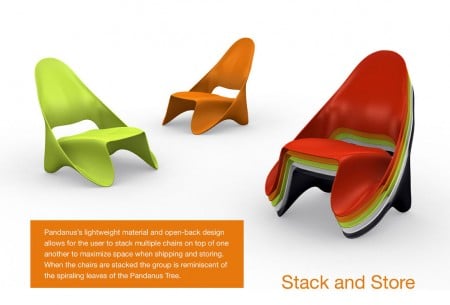

Pandanus

Jessica Konawicz

Jessica Konawicz found inspiration in the furls and fronds of the Australian Pandanus tree, whose cradled leaves reminded her of stacked chairs. Tracing over the lines of the leaves and fruit, she found shapes that intrigued her but also discovered the possibility of a single-material form that could do many things at once-support the body comfortably, use little surface area and material, ship and store efficiently, and present an elegant, inviting image. To be made from a cellulose-based, biodegradable plastic, Pandanus could be produced using only water, natural additives, and plant fibers. Sprayed onto a mold, the mixture yields a material with strength similar to fiberglass. The jury loved the elegant, fluid form and its clever stacking function. Some were concerned about its comfort, however. Konawicz designed the form around statistical dimensions for 90th percentile men and women and, in her words, a “relaxing angle” of 110 degrees, but some judges worried that the seat area is too low and may force the pelvis forward, reducing lumbar support. One judge who liked the design nevertheless suggested that, given the low height, “you might as well just sit on the floor and scratch the need for a chair altogether.” Yet, the image nevertheless swayed us, possibly beyond a fully rational explanation-a great example of our call for designs with “emotional resonance.”

Posi+ive Lounge

Jittasak Narknisorn

If the Pandanus is the exemplar of one criterion, the Posi+ive Lounge embraced all three equally. Jittasak Narknisorn began by experimenting with paper, thinking that if he could shape the form with his own hands, then manufacturing it would be easier. Working the paper like origami, he eventually found an extraordinarily simple solution-a pure rectangle with four fold lines and four plus-shaped cuts. The cuts and folds allow the surface to be bent into a surprisingly stable shape that subtly cradles the body. Galen Cranz, our comfort expert, ranked this the smartest “body conscious” design after the adjustable Jingai chair. A continuous steel bar holds the shape together, supports its weight, and provides arms allowing the occupant to sit down and get up easily. A wool felt cushion softens the seat-one of the few upholstered chairs in the competition. While the design doesn’t strike me as having the same aesthetic power of the Pandanus, in my mind it most closely demonstrated all the principles of the competition. Minimal waste with great support and elegance-in Narknisorn’s words, “a nice, clean, comfortable shape.”

The two winners each received $2,500, while the runners up took home $500. Narknisorn and Konawicz also were brought to the Las Vegas Market in July to participate in the awards ceremony scheduled during the annual design event at the World Market Center. Inglis, Casey, Szenasy, Wollaeger, and I were on hand to present the awards and discuss the competition. A terrific conversation about the future of the program led to an ambitious plan to stage the competition so that the finalists would receive seed money to build a prototype, judging of which would take place in person. But that’s next year.

Architect, designer, and writer Lance Hosey is a Director with William McDonough + Partners. He has been featured in Metropolis magazine’s “Next Generation” program and Architectural Record’s “emerging architect” series. He is a Contributing Editor with Architect magazine and co-author (with Kira Gould) of Women in Green: Voices of Sustainable Design (2007).