July 17, 2017

The Art of Unfinished Spaces: An Interview with Pei Zhu

Leading Chinese architect Pei Zhu on working without a signature style, taking nature as inspiration, and crafting unfinished spaces.

For at least a decade China was considered the world’s biggest playground for starchitects. Now the situation is turning around; today there are at least a few dozen world-class Chinese designers – from middle aged to youngsters in their 30-s and early 40-s – who have succeeded in developing distinctively contemporary architecture that is more based on local traditions than global influences. On one of my five trips to China this year, I caught up with one of the country’s leading architects, Pei Zhu, who opened his Beijing Studio Zhu-Pei in 2005 and has already built a variety of cultural, educational, and hospitality projects all over China. His work has been widely exhibited and awarded internationally. His inspiration may not be surprising or unique—nature—but his solutions are remarkable and enlightening.

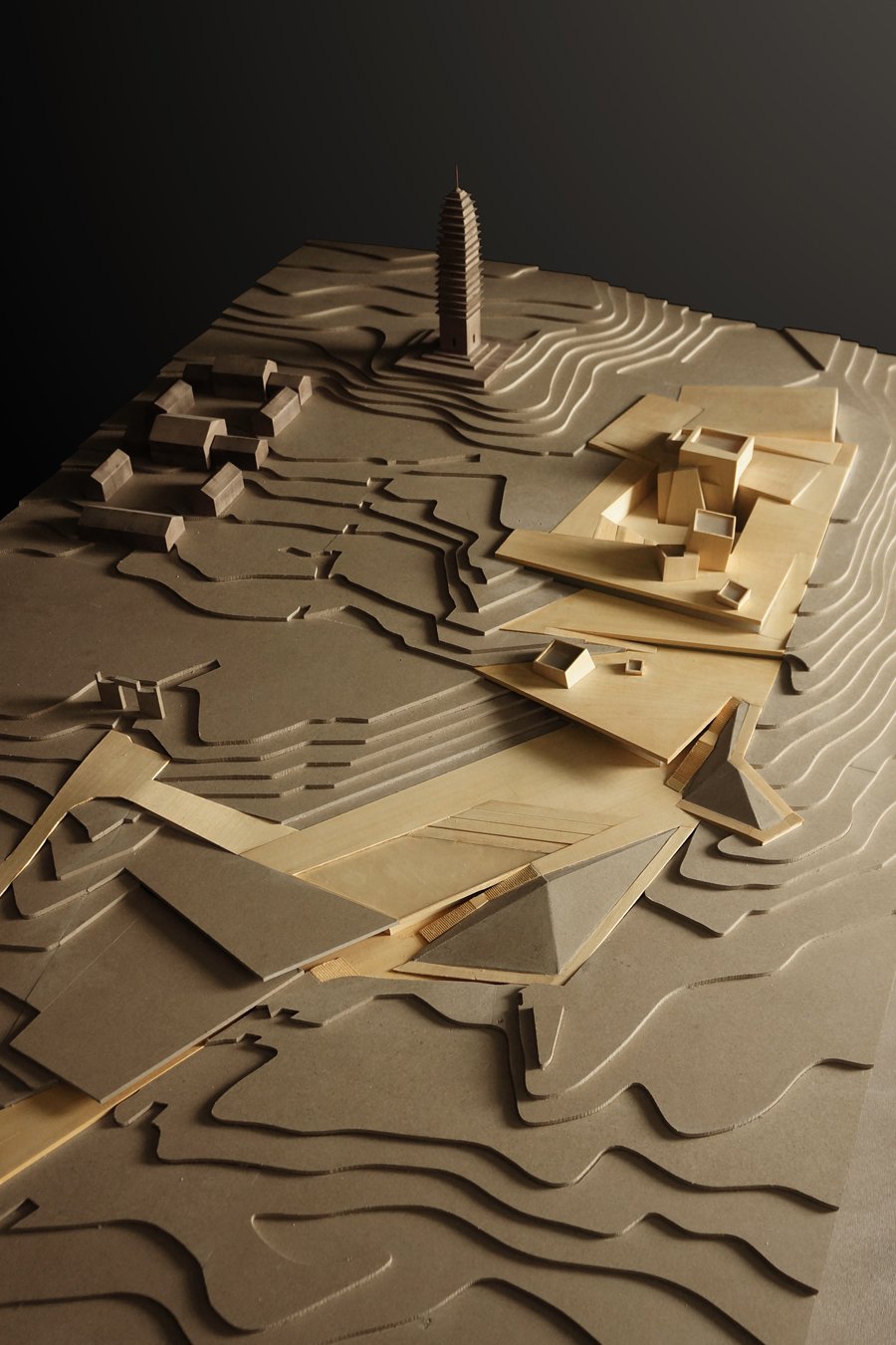

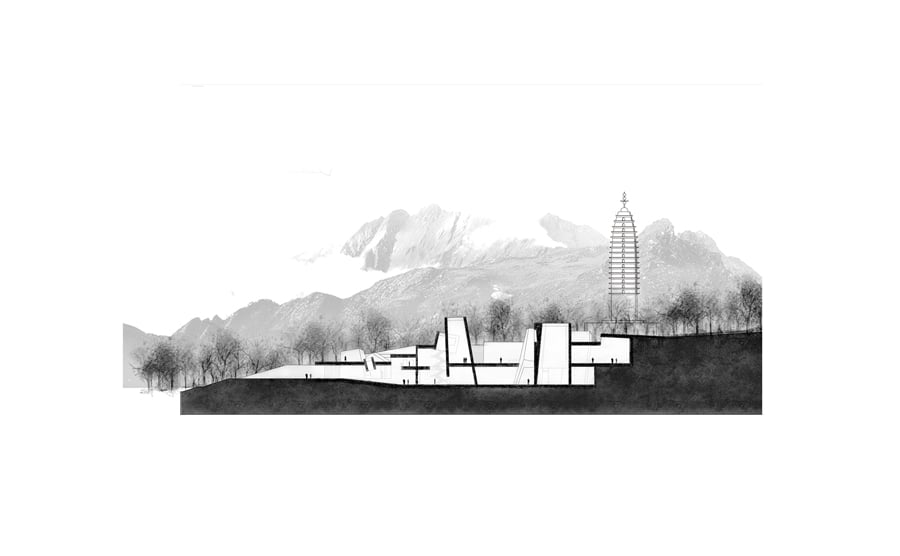

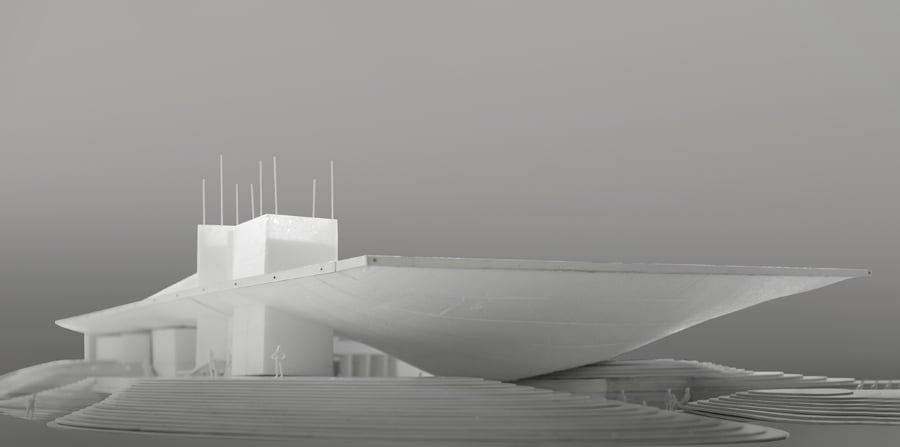

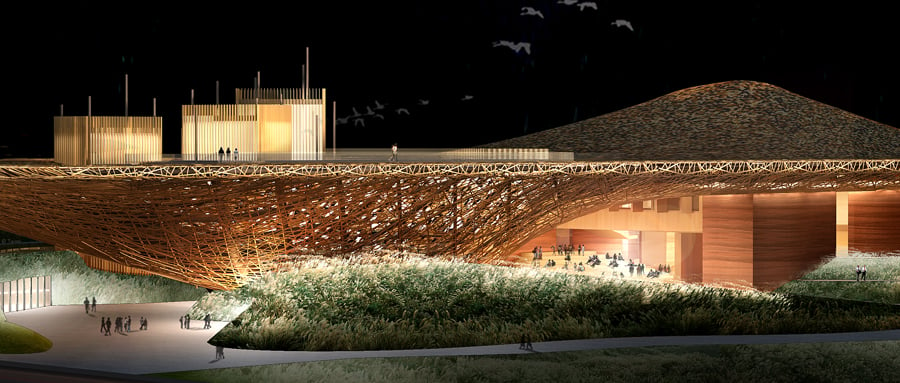

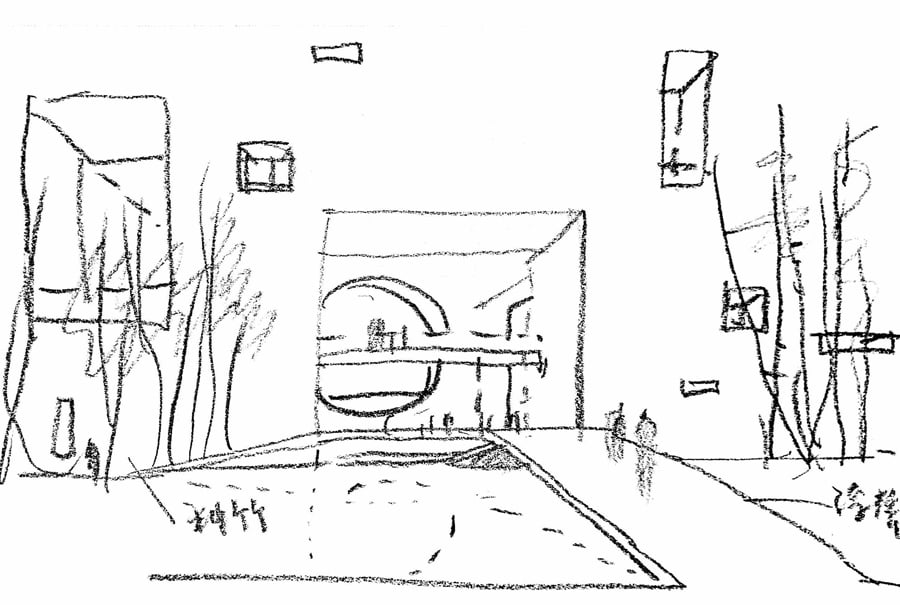

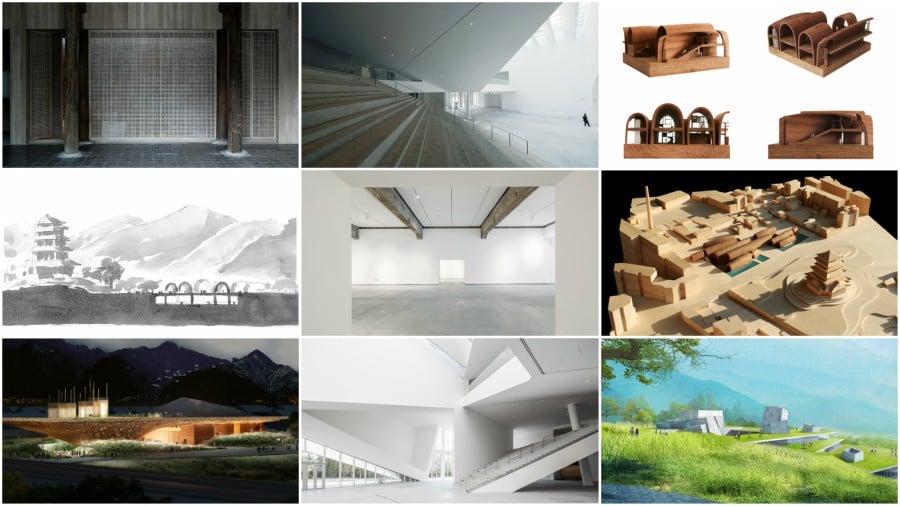

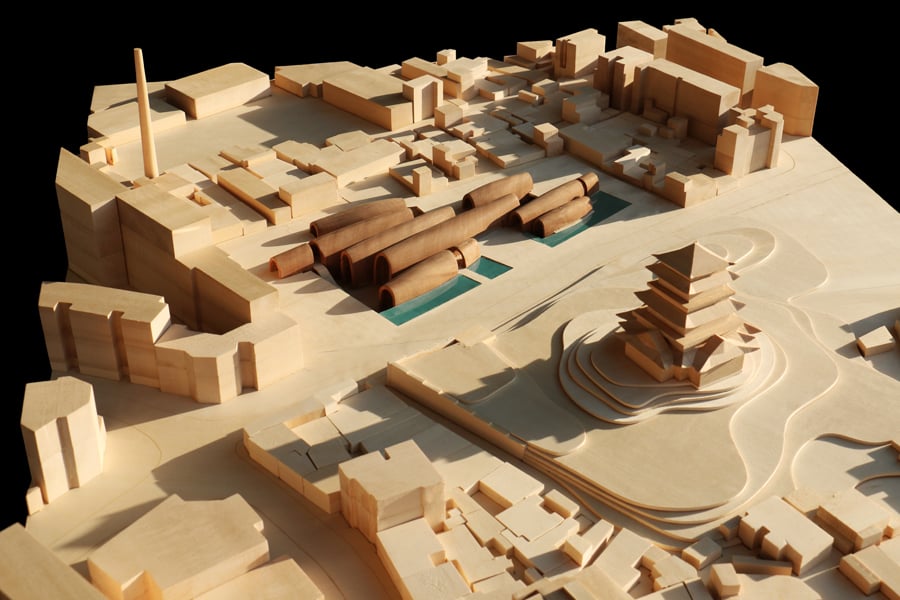

Pei Zhu: More than half of all the models that are usually on display here in my studio are currently being shown at Aedes gallery in Berlin; the show is called Mind Landscapes. There are five projects on display – Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum, Yang Liping Performing Arts Center, Dali Museum of Contemporary Art, Shou County Culture and Arts Center and Shijingshan Cultural Center—all currently under construction. I wanted to show my current thinking and design process and a range of interests based on place, climate, culture, lifestyles, local materials, history, and most of all, nature. I want my architecture to reflect all these particular conditions, learn from them, and create a new experience, which would be very specific for every place.

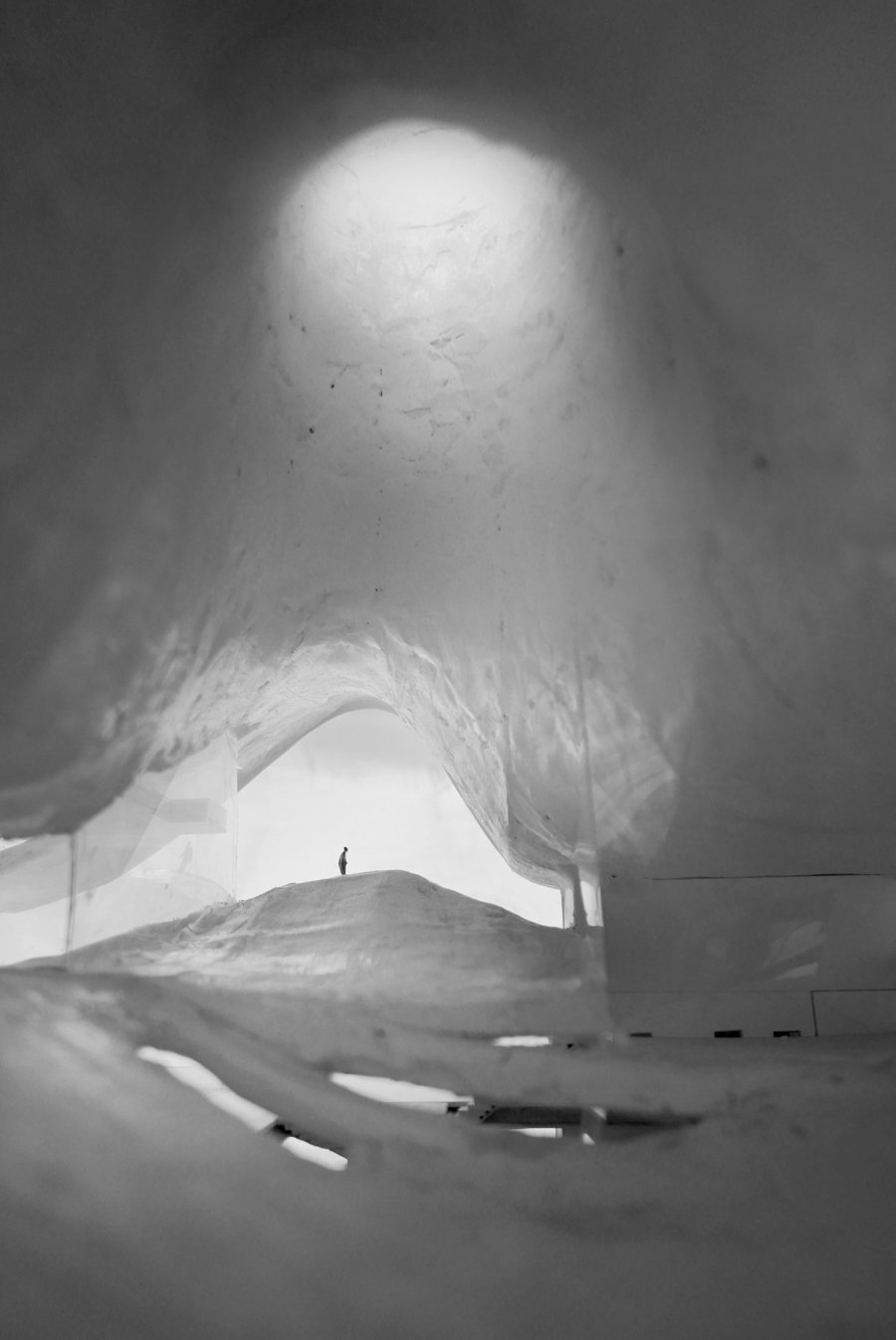

Vladimir Belogolovsky: You mentioned that nature is the most important of your inspirations. But when I look at the photos of your exhibition in Berlin, the layout is very geometric and abstract. And almost everything there is represented in white. Even your landscape drawings are in black and white.

PZ: Most people associate nature with green, with mountains and the forest. But today most people live in cities. In my work, I don’t emphasize physical nature, unlike so many other architects who try to mimic nature literally, with greenery that covers their architecture. That is not real nature. I never try to make my architecture look like nature. It is impossible anyway. The idea is to respond to nature, not to copy it. For example, many good ideas can be learned from traditional houses with tall courtyards, solid walls, and small windows as a response to a hot and humid climate. So for me nature is attitude; it is all about our attitude towards how we respond to the climate. Architecture should be about how we want to respond to and build our relationship with nature. Also I don’t like buildings that express technology or cover themselves in expensive, shiny materials. That’s very pretentious.

VB: Looking at your works currently under construction—the Imperial Kiln Museum in Jingdezhen, Yang Liping Performing Arts Center in Yunnan—or your other well-known earlier works—Digital Beijing, Blur Hotel in Beijing, OCT Design Museum in Shenzhen—it is hard to believe that all of these projects were designed by one architect. Why are these works so different? What are the main intentions behind your architecture?

PZ: I strongly believe in the specificity of each project. Climate is one of the key reasons for finding very different solutions and expressions. You can’t apply one standard stylistic approach. A number of architects developed their signature styles. I am not interested in that. I am modest in that respect, and I would rather design architecture that’s specific and not personified or recognized. So the materials and forms I use are always different.

What never changes is my attitude – I always aim at creating something beautiful to complement nature. My favorite architect is Le Corbusier, and he changed all the time. His monastery La Tourette and chapel Ronchamp were designed around the same time, but you can’t find buildings that are more different. Because the sites are very different, the programs, and the scales, the resulting forms are very different. But if you go beyond these buildings’ forms you can find similarities in the materials, colors, the way the light is treated, and in their relationships to nature.

VB: There is a bit of a contradiction in the idea of bringing well-known architects to other places to express something local, don’t you think? For centuries, it was all about inviting accomplished architects from overseas, so they could bring with them something new, personal, even iconic. Bernini’s invitation to Paris by Louis XIV is a famous example. Today, just like every museum wants to own a Picasso, every city wants to build a building by Hadid…

PZ: That’s not true… Not anymore!

VB: You already have two huge built works by Hadid here in Beijing…

PZ: There must be balance. As an architect, you need to create the experience that people know; then you need to try to create the experience that people don’t know. That is perfect architecture. Architecture is not about creating something strange. Architecture is not sculpture. It is all about the experience, about going inside, exploring, getting excited. So many new cities are built based on the latest fashion or like theme parks rather than real cities. But I believe in architecture that’s rooted. If you build in China, you have to connect it with local Chinese culture.

Architecture should be based on two fundamental principles – one is the root and the other one is innovation and new experience. I think you need to combine revolutionary thinking and respect for local culture and conditions. Architects coming from a different place have an advantage of seeing things differently. That is very important.

VB: If I asked you to name single words to describe your work, which words would you choose?

PZ: Two words that I already named – root and innovation. The root is associated with nature and culture, and innovation is all about the new experience.

VB: You called your approach to architecture a non-architecture style.

PZ: Because I hate the idea of having a style. I don’t have a style. I want to be different every time. I want to be more experimental. I want to forget what I have done in the past.

VB: Do you see architecture as art and do you believe in the concept of architect as artist?

PZ: Yes, I strongly believe that architecture is art. And if architecture is art this means that architects are artists. Why do we call some people artists and others designers? Artists create something that didn’t exist before. They create new perspectives, new experiences, new ideas. But there is a difference between architecture and art. Architecture is not only about space but also about function and experience. Art is created for everyone. But architecture is very specific. Architects create buildings for specific people, places, cultures, and climates.

VB: I would like to ask you to comment on some of the following of your own quotes. You said, “The most important moment for architecture is not the completion of the building, but when the spaces intersect with people.”

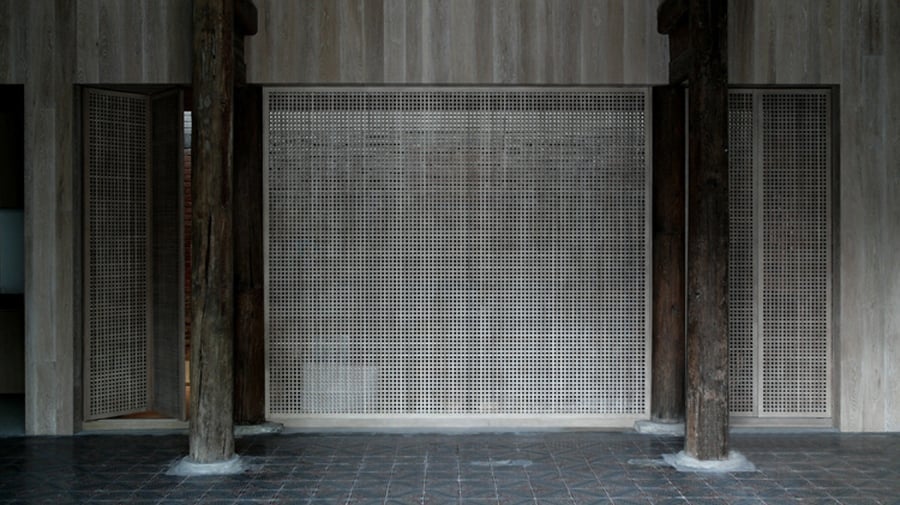

PZ: When you look at a traditional Chinese painting, it looks incomplete. It is the job of the observer to complete the painting in his mind. Chinese scholars never set down in front of mountains to sketch them, they would travel for months in the mountains to experience them. When they came home, they would try to recapture these moods by putting together all their memories in the paintings. Chinese gardens and architecture are also focused on the experience, on creating spaces to walk, view, live, and roam. No building should be completely finished. There should always be some space left for people’s interpretation. Architecture should be just like a Chinese painting; it should strive to prove possibilities beyond the immediate function. A building that’s created just to perform a particular function is a dead building. Look at the traditional hutong with its courtyard in the middle. There is no particular function for that. It is just emptiness, but it also means everything. People eat in the courtyard, socialize, get married there. We call it the incomplete space. But this is the most important space in the house, its heart. When we work on our buildings, we try to avoid providing finished solutions; we leave space for interpretation, so different functions can be imagined beyond our own expectations. A building should be like a sponge; there should be many incomplete spaces in between.

PZ: For example, when I did a courtyard house for artist Cai Guo-Qiang here in Beijing it was mostly a renovation of a historical hutong, but the part that was damaged beyond restoration I rebuilt as a new pavilion without trying to copy anything. I used new, even futuristic materials and forms to contrast with the old ones. It was a very ambitious project; some would call it ambiguous, but to me this way of juxtaposing old and new is about respecting the past, while moving into the future. Most people would see this example as contradictory, but for me this is how I search for a new harmony. In every project, I look for opportunities to express my work in the most contemporary ways.

VB: You have also said: “You cannot just use traditional tiles and then claim that this is traditional architecture.” Was this a criticism aimed at your colleague Wang Shu?

PZ: Not really. Different architects have different approaches. I admire Wang Shu’s work very much and we share many ideas. He is looking for the root; I am also looking for the root. What I was criticizing in that quote is using new materials to copy traditional imagery. Wang Shu’s work has a deep soul. He uses recycled material, which I like, and, in fact, I am now working on the Imperial Kiln Museum in Jingdezhen where I am also recycling local bricks, which was a local tradition. The kiln structures needed to be rebuilt very often and the workers recycled the old bricks to build their houses. So there is a strong culture for recycling and repurposing building material.

VB: And the final quote: “Our studio has always been geared towards the future.”

PZ: Yes, I am always looking for ways to create new experiences, something that did not exist in the past.

VB: What are your favorite buildings?

PZ: Acropolis in Athens, also some traditional villages in China. I like getting inspiration from buildings that were built based on collective thinking and not driven by one person’s ideas. There is something natural about how these structures were developed. And in our attempts to build the future we have to study and know the past. Also unlike many traditional structures in the West, such as Neoclassical palaces or the Forbidden City here in Beijing, a primary axis and symmetry are avoided. There is this approach of adapting architecture to the place, which I like. I feel that this architecture was done as a careful collaboration with nature.

VB: If you had a chance to have a conversation with any one architect, who would that be?

PZ: Le Corbusier. He was so great. I love his very artistic mind and dynamic, innovative architecture.