July 19, 2017

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Life, In Hipster-Friendly Illustrations

Despite its styling as a kids book—the illustrations are cartoonish in the way Chris Ware’s are—this biography is a substantive account of Wright’s life and work.

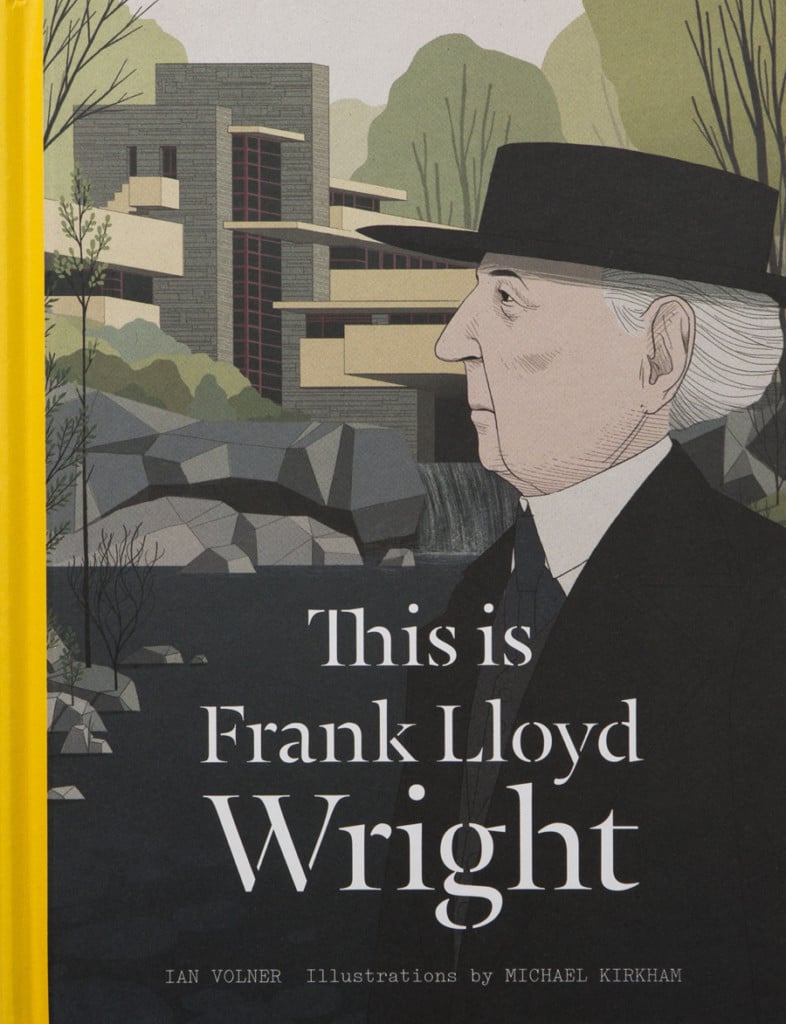

Given all that’s been published about Frank Lloyd Wright, another introductory volume on the architect might seem superfluous. To illustrate that volume, and so invite comparison with the drawn works of Wright and his studio, might seem ill-judged. Yet This is Frank Lloyd Wright (Laurence King, 2016) succeeds at doing both, in a book that is slim but substantive, aided by an excellent set of illustrations.

There are the usual highlights here, as there must be, and yet for such a succinct account (at 80 pages), there are a surprising number of finely wrought details. Wright’s compulsive need for designerly control extended to the furnishings of his homes, but the book’s author, Ian Volner, reminds us of the architect’s regard for ceremony, at the expense of basic ergonomics: “The chairs often featured high backs and low seats in an effort to impart a feeling of empowerment to the sitter, a throne-like aspect that, unfortunately, is rarely comfortable, especially for taller people.” These welcome descriptions are peppered throughout; for instance, Volner notes the purposeful absence of gutters at Taliesin, Wright’s main home in Spring Green, Wisconsin, to encourage the picturesque growth of icicles. Other facets of Wright’s person and design methodology, including his unaccommodating manner to clients, are encapsulated with maximal concision: “So complete was his conception of the harmonious environment that his clients often found there was no place to put such things of their own as they already had.”

Despite its brief length, Volner’s narrative dodges simple synopses. Take the Prairie School, which could easily have been described in a few sentences in the ways it always is. Not so:

But the Prairie School is not as simple or homogeneous a movement as it’s often thought to be. First there is the question of authorship: Wright is typically viewed, and viewed himself as the father of the style, but the environment at Steinway Hall was a real cooperative workshop. … Most of the Prairie School members weren’t even from the Prairie, and their work went in very different directions in their later careers, from high Art Deco to Spanish Colonial. If it was really “prairie,” it was so almost by accident of geography; and if it was a “school.” then it was one in which Wright was not the principal, as he often proclaimed, but perhaps only its most illustrious graduate.

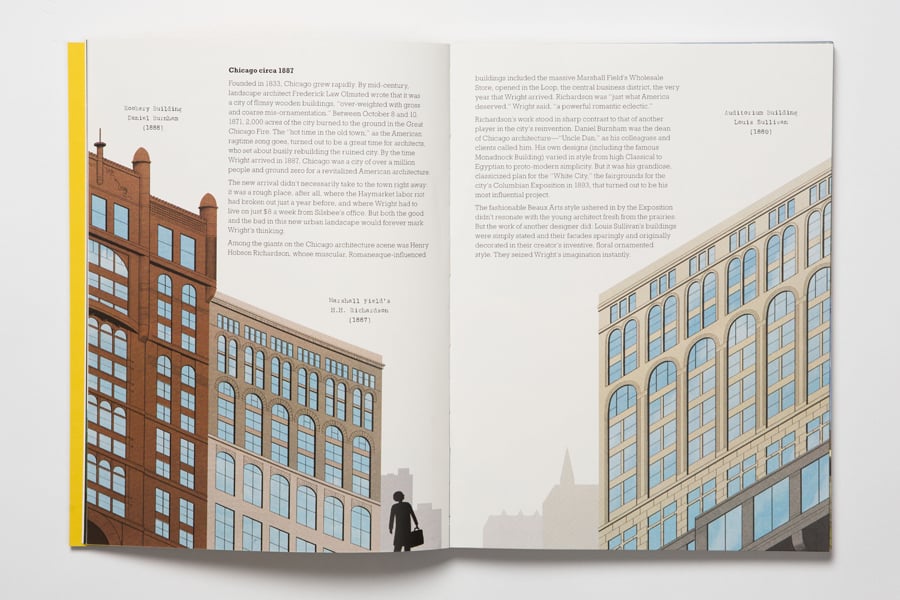

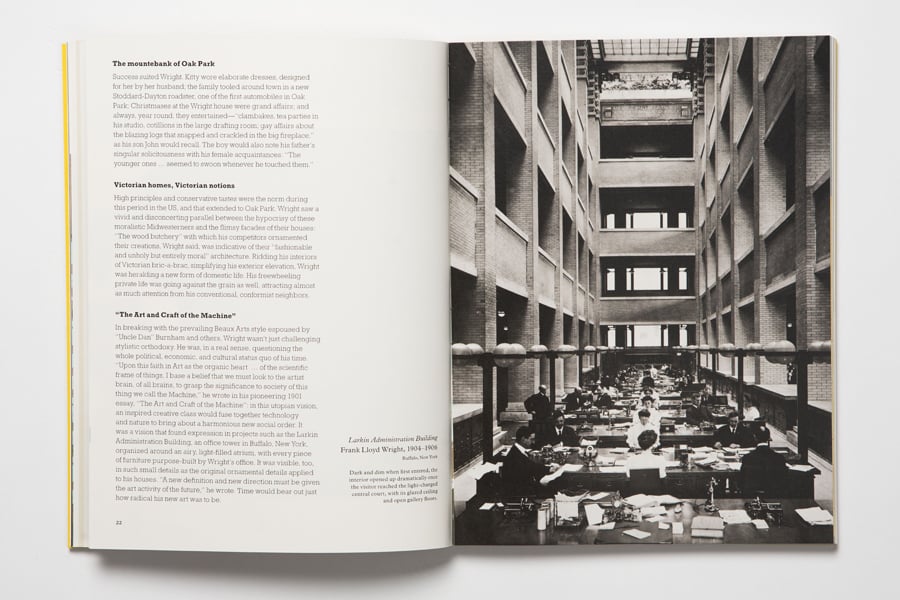

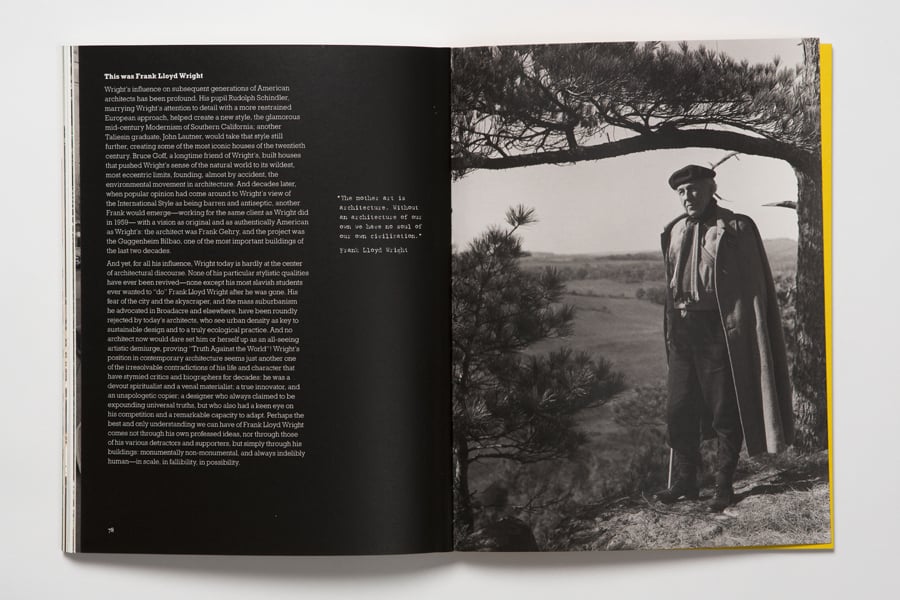

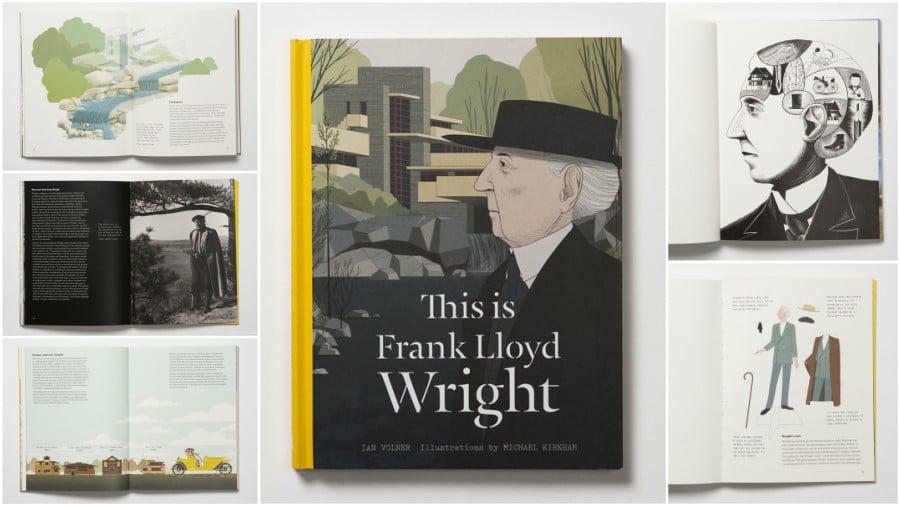

This is all very capably accentuated by a selection of photos but particularly by Michael Kirkham’s excellent illustrations, which betray a clear fondness and facility for architectural rendering. The pairing of Volner, an architectural journalist (whose much longer biography of Michael Graves is due out in this fall), and Kirkham, an Edinburgh-based illustrator whose work has been featured in The Guardian, the Telegraph, and The New Yorker (a drawing of Renzo Piano’s Whitney might be familiar), is the latest in publisher Laurence King’s successful Artists’ Monographs series, which includes volumes on Jackson Pollock and Henri Matisse. Text and image are so complementary as to be inseparable.

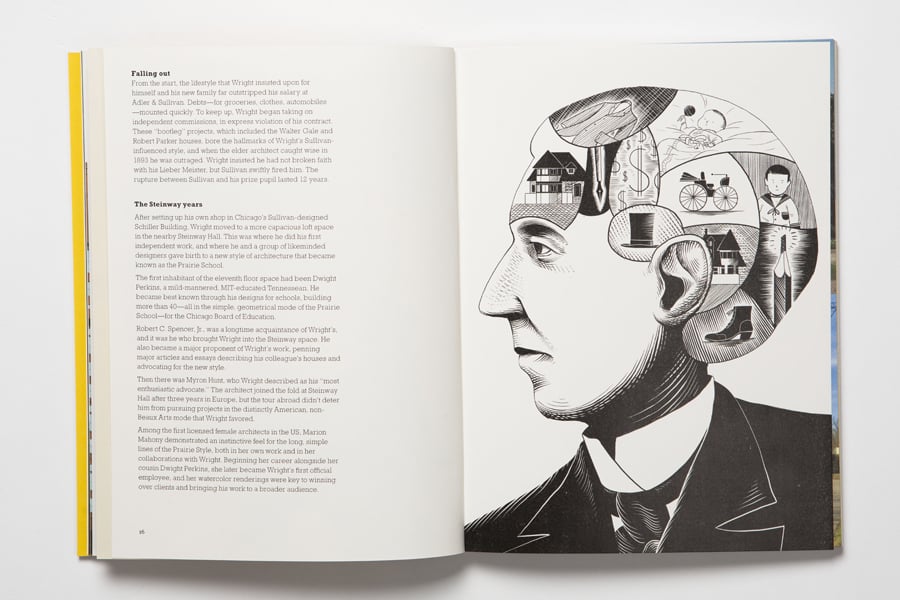

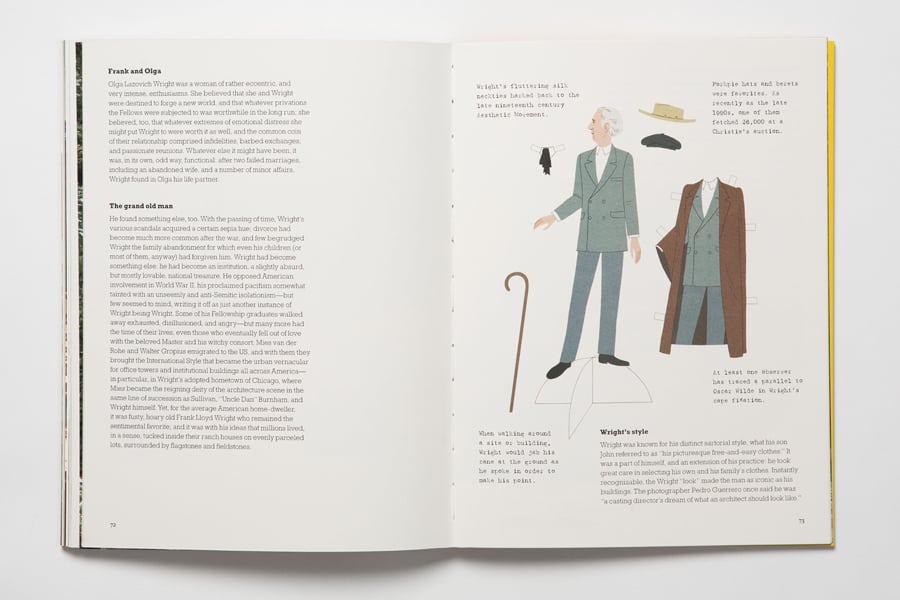

There’s only one Wright drawing in the book, but even if there were more Kirkham’s style is a fine contrast. An assortment of Wright furniture is presented in mock mail-order catalogue form, while other drawings resemble daguerrotypes or cut-outs. A page on Wright’s sartorial splendor features him as a paper doll, with tabbed cape, hats, cane, and other accessories (but you really wouldn’t want to deface this book). Another splendid moment pairs the Wright quotation “Why not carry the floors as a waiter carries his tray on upraised arm and fingers at the center, balancing the load” with an illustration of a waiter’s hand holding the Imperial Hotel (1923) aloft.

Kirkham’s style, old-timey yet contemporary, flat yet still conveying depth, is a bit like Chris Ware’s, although a resemblance that seems mainly due to their both being keen students of vintage print and comic styles. Their architectural renderings are similar but subtly different: if Ware’s metier is the full cross-section, Kirkham trades in the more selective revelation of the cutaway. Wright’s Oak Park home and studio, a Usonian house, and the Guggenheim are each strategically revealed through the technique. These selections are purposeful; portions of roof and wall are pulled off of the Usonian home to illustrate programmatic function, not merely to allow the reader to peek inside.

The book happily points us onwards, at its end, not to misty Usonia but to a sober assessment of Wright’s legacy. Volner notes the absence of a real school of Wright and of the dramatically varied directions that his most eminent students and followers took, from Rudolf Schindler to John Lautner to Bruce Goff. The only flaw might be the heavy attention to Wright’s personal life at the expense of his work, but this is the story of so many larger Wright biographies that it can easily be forgiven in a short one. If scandal—and Wright’s life was ridden with it—draws in new fans, it’s done its work here, yet again.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also like “Finn Juhl: Master Painter, Master Designer.”