November 8, 2017

Rediscovering the Social Aspirations of Israel’s Early Modernists

A new exhibition at Yale School of Architecture distills social values from Israel’s early Modernist Architecture.

Modern architecture has been alternatively praised and panned since its emergence in the earlier parts of the 20th century, yet its underlying social ideology and intentions are often overlooked in favor of investigating its formal elements and aesthetic qualities.

The type of Modernism brought with Jewish immigrant architects to British Mandatory Palestine prior to the founding of the State of Israel in 1948 demonstrates its sincere attention to a human dimension, in contrast to Europe’s more theoretical discourse. This divergence is the subject of Social Construction: Modern Architecture in British Mandate Palestine on display at the Yale School of Architecture. Ideologically and technically far-reaching, yet narrowly defined in scope, the exhibition illuminates the relationship between the formal aspects of the architects’ designs and the social and socialist aims embedded within.

“Palestine’s distance from the cultural centers where Modern architecture had defined itself made the local landscape an ideal ground on which to explore this new dialect,” the show’s catalogue asserts. “Architects in Palestine were actually building it.”

The exhibition is comprised of three distinct sections. The first, titled “Architectural Precedents,” focuses on the three cities in which the immigrant architects to Palestine primarily worked (and which continue to define the Israeli urban system) — Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Haifa. Tel Aviv, considered the “First Hebrew City” takes center stage and signifies Zionism’s initial desire to break from Jews’ diaspora past. It was the primary spatial canvas upon which young architects such as Dov Karmi, Oskar Kauffmann, and Zeev Rechter, projected their ideological and aesthetic leanings. Jerusalem and Haifa, meanwhile, were characterized by preexisting Arab settlement and culture, and were thus less susceptible to the tabula rasa approach to urban development so favored by the Modernists.

The exhibition’s second and main section, called “Emergence of a Modernist Language” and initially displayed at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, was curated by architects Dan Price and Ada Karmi-Melamede, winner of the prestigious Israel Prize and Karmi’s daughter. It is here that the core of the story of pre-State Modern and International Style architecture plays out, where detailed formal analytic, axonometric, and interpretive drawings of (mostly) residential Modernist constructions convey the socialism, utopianism, and communitarianism that defined Zionism of the time. Seeking a clean break from the horrors of European anti-Semitism and pursuing the establishment of a new society, the Zionist architects sought to eschew the monumental scale of British colonial architecture and the historicism and fixedness of local Muslim and Oriental vernacular.

Wandering through the exhibition, designed by architect Oren Sagiv, one feels immersed in the distinctly Mediterranean high Modernist city. “They wanted, as you move through the show, to feel like you were on the street, with the faces of the these buildings looking at you,” says Andrew Benner, the architecture school’s director of exhibitions. The relative similarity of individual buildings in style, scale, and color (invariably white), especially in Tel Aviv, meant that they often “came together as homogenous urban facades,” according to Benner, an unpretentious sameness that scaled up the modesty of a single construction to the urban-level.

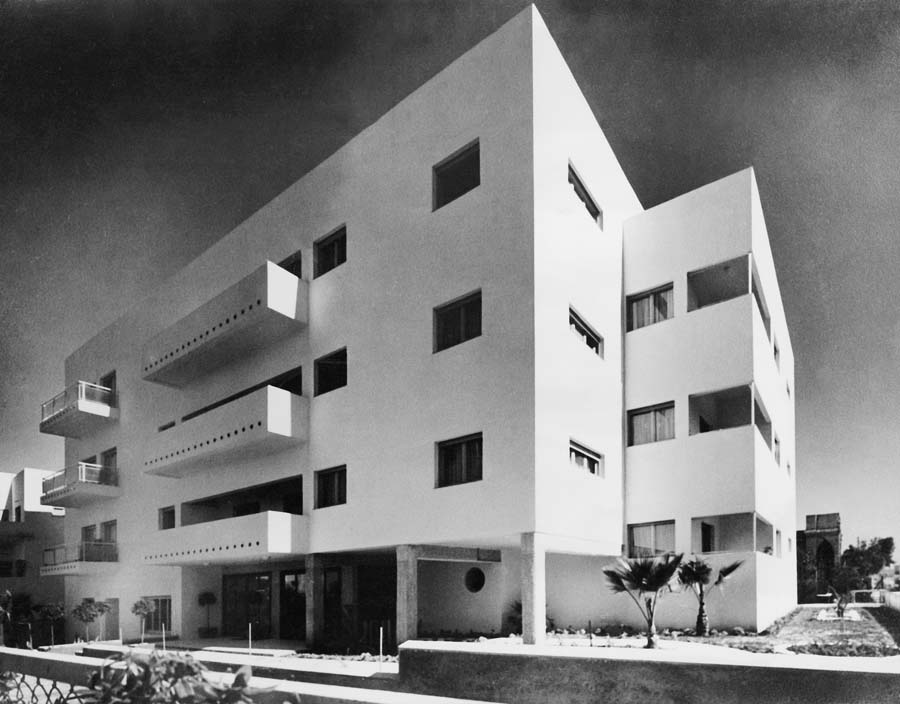

“Emergence of a Modernist Language” is organized by built element, each implying how modular aspects like courtyard, facade, stairwell, and balcony both represented Modernism’s social idealism and were tailored to accommodate local climatic conditions. For example, glassless and deep-set windows and ribbon balconies create deep shadows that protect units from desert wind and intense sun (Karmi’s well-known Liebling House characteristically embodies these features). Stunning archival photographs and meticulous formal analyses by Karmi-Melamede and Price (with a team of students) deconstruct the buildings’ designs to their constituent features in order to distill guiding social values.

The communal ideals and aspirations of the pre-State architects are made evident in the photographs and drawings of the buildings, primarily residential, but also encompassing civic structures and workers’ housing, such as a complex designed by Arieh Sharon at Frishman and Frug Streets in Tel Aviv. Communal roofs, internal courtyards, open spaces at ground level, and public foyers were all meant to be facilitate social life in the nascent society. “They’re really trying to not just record [these elements] but extract from them some kinds of principles,” says Benner. “The kinds of communities they were dealing with wanted those spaces.”

An important design technique that runs through this section is the deliberate blurring of public and private spaces, what Benner calls “a middle realm between the private home and the street.” The complicating of boundaries between sidewalk, street, wall, building, and voided space was meant to further encourage the development of a new society defined by a certain utopianism. The architects, says Benner, “were less interested in the individual building than what they added up to.”

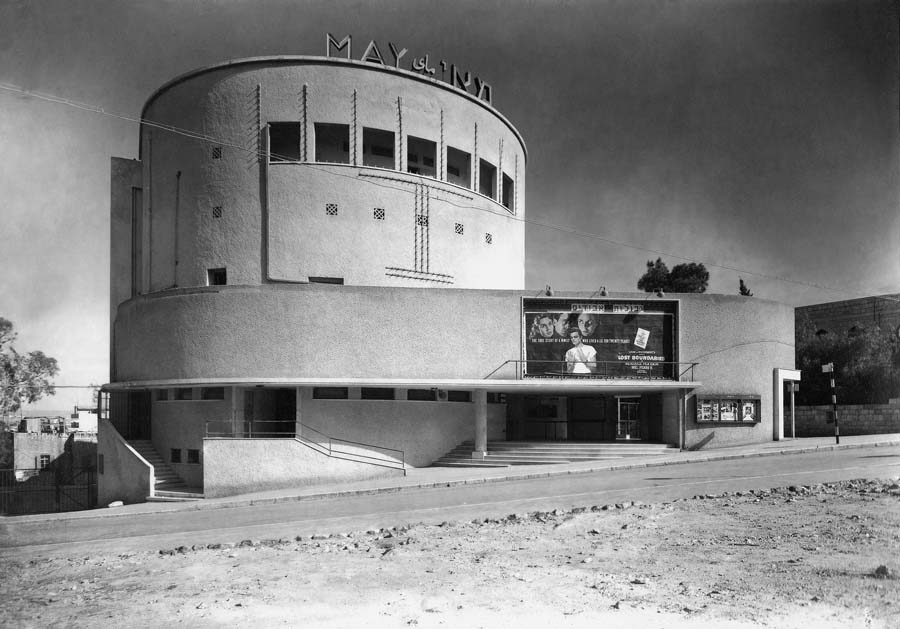

The third and final portion of the exhibition, also a new addition to its presentation at Yale, is called “Hybrid Modernism” and looks at how the “pure” Modernism was later adapted, reinterpreted, and recast, shaped by, among other influences, indigenous Arab architecture and British imperial projects. Stone, for example, is gradually introduced into Modernist constructions in Jerusalem, and arched doorways and fenestrated courtyards mark the architects’ gradual grappling with, and accommodation of, local styles.

The multifamily Rubinsky House, designed by Lucien Korngold and situated at the intersection of Sheinkin and HaGilboa Streets in central Tel Aviv, is characteristic of this period, when architects seized greater freedom in adding ornamentation and mixing multiple, curving facades and street orientations into one construction. The design is simultaneously introverted and extroverted, combining three distinct volumes within a single, stretched “skin,” granting the luxury of space to its inhabitants while relating to the “larger urban order,” according to the exhibition’s text. While still typically Modernist in style, the building’s design (and this period more generally) betray a “tension” that allows “multiple architectural aspirations to coexist,” according to the catalogue.

As with nearly any public undertaking that involves mention of the words Palestine, Israel, or Zionism, the exhibition has stirred debate — in this case, within the pages of the department’s student publication Paprika! For Dima Srouji, a Yale School of Architecture alum, the exhibition “does not acknowledge non-Zionist participation in representing and establishing the International Style in the area.”

“These architects,” she continues, “were superimposing new architecture that was foreign and separate from the regional spirit of place in a context they viewed as a blank slate.”

Dima’s critique is unquestionably valid in that that the show focuses on the spatial and architectural manifestations of Zionism exclusively, yet as defined by its original communitarian- and socialist-oriented ideology rather than its current, more polarizing iteration often understood through territorial conflict and interethnic inequity. But Karmi-Melamede, at a gallery talk, emphasized the distinction between the present-day Zionism and Zionism as a historical ideology or moment. The latter is instrumental in understanding the history of Jewish immigrant architects and planners in Mandatory Palestine — how they lived, worked, and thought.

A 1937 photograph at the very entrance to the gallery brings this idea to the fore: Depicting Dizengoff Square — still one of Tel Aviv’s primary civic squares — the image shows pedestrians and bicyclists inhabiting the open, fresh urban fabric, neatly organized and, in parts, still under-construction. The vibrant social life of the newly-established city is made vivid. According to Benner, the photograph “tells the story of what Karmi-Melamede is trying to say — the idea of creating a public realm.” In other words, social construction at its best.