January 23, 2018

Once Unfashionable, John Portman Is Being Seen in a New Light

While a previous generation condemned the joining of architecture and development in a single figure, few young architects are unpersuaded by the monumental products of Portman’s efforts.

When the late architect John C. Portman Jr. first set up his firm in Atlanta, in 1953, it was in a single 300-square-foot room and bankrolled by a $100 loan. More than six decades later, the firm’s employees number in the hundreds and many of its scores of completed projects are towering, often Baroque monuments to a bygone era of architectural audacity. The most memorable of these, nearly always enormous and even glitzy buildings, are appreciated by the general public, even while perennially dismissed by the academy. Portman died in December, but even before then there had been signs that some in the architecture world were reconsidering his work. In the wake of his passing, many practicing architects took to social media out of recognition for the man’s broad influence. In fact, work on this article had begun weeks before his death, but Portman missed an interview because of his declining health.

Portman’s sprawling portfolio has, until recently, been given scant historical attention. Architecture historians and theorists are beginning to look back on Portman’s career and the era to which he belonged, and a younger generation of architects sees much to admire in “Atlanta’s architect,” as he was sometimes called. Models of his Peachtree Center, the downtown Atlanta district he designed and developed continuously until the 1990s, were exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2010. And the new book Portman’s America: & Other Speculations (Lars Müller), edited by Mohsen Mostafavi, dean of the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, is a sumptuous example of this growing interest. Judging by the book’s wide range of critical interpretations, his legacy in architecture is not yet settled.

He may have been a victim of his own success. For Sylvia Lavin, an architecture theorist and curator based in Los Angeles, Portman’s professional productivity ran counter to the criteria of success established by academically minded architecture critics in the second half of the 20th century. “The academy had become the place that established the standards for importance,” she says. “From the 1950s to the 1990s, there was an increasing distinction between success in professional terms and success in disciplinary terms, to the point that it became almost impossible for the two to exist simultaneously.”

Portman nevertheless tried to have it all, coming up against the ire of the American Institute of Architects, which claimed that an architect who was also a developer represented an irresolvable conflict of interest. From the perspectives of both the profession and the academy, Portman’s Janus-faced role made him the exception that proves the rule. “Every moment that Portman succeeded in practice, he lost favor in the academy,” Lavin says.

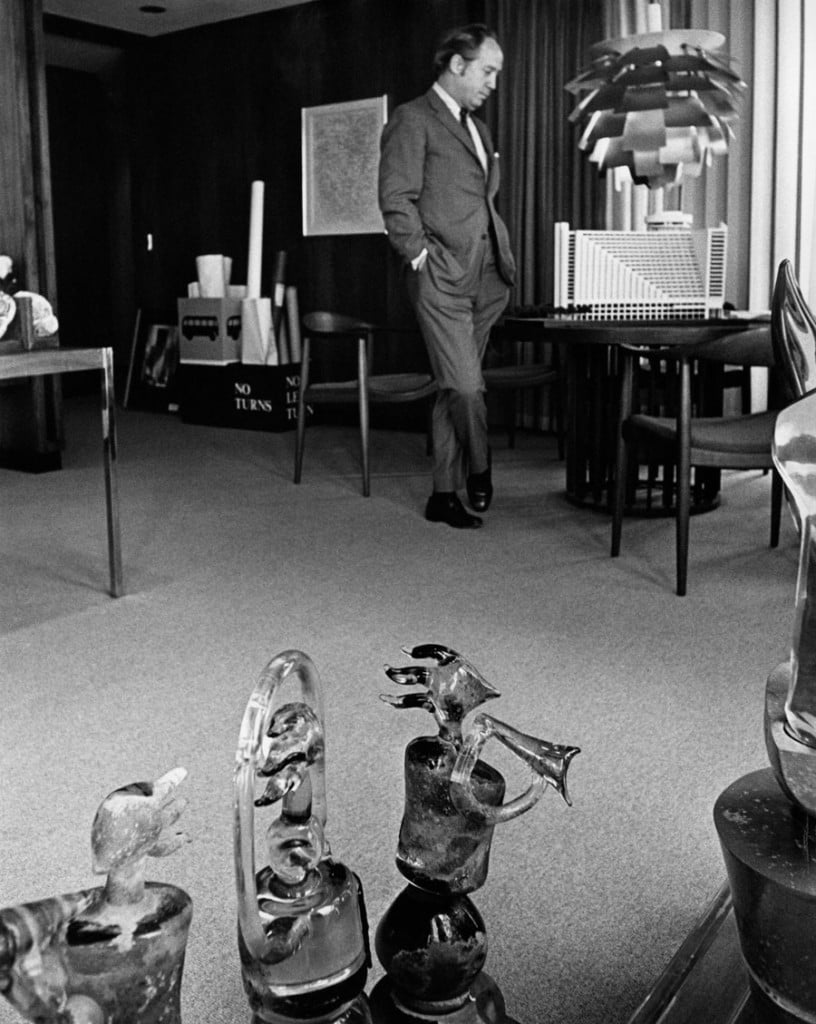

Courtesy Gerald Crawford/The John C. Portman Jr. Collection/The Portman Archives, LLC

His professional rise was rapid and early, but his first years in practice were not without frustration. Opening his own office immediately after receiving his license, Portman set out on his own without any commissions or leads. His first project, coming just a year later, was a humble one: renovating the local lodge of the Fraternal Order of the Eagles, in Atlanta. Portman, who was a lifelong artist, insisted that a bronze sculpture of an eagle adorn the new streetfront facade and was not deterred when additional funds to cover its expense were not forthcoming. He ended up footing the bill himself and donated the eagle as a piece of public art. The experience was one that pushed Portman to take on real estate development as a role parallel to architectural design. In a 1983 conversation with the architect Peter Eisenman, Portman recalled being discontented as a young architect dependent upon his clients’ finances and decision making. “I came to the conclusion that if I were to have an impact—and not be just part of a process I could not control—I should understand the entire project from conception through completion,” he said. “That led me to real estate.” In his view, taking on the development side of construction afforded him a degree of artistic independence and a greater measure of control that opened the door to the boldly original design language that would become his hallmark.

In 1961, Portman’s foray into real estate development paid off. The Atlanta Merchandise Mart, finished that year, was the first built project with him as both the developer and the architect. It was also his largest building to date and, at the time of its construction, the largest structure by floor area in Atlanta. A concrete behemoth, the structure was built around Portman’s acute sense of a business opportunity, transforming a downtown office building—what had once been a parking garage—into a wholesale trade hall of a quarter-million square feet. The project, now part of AmericasMart, was a runaway success, and new wings have been added as recently as 2008. (The complex is now appraised at $1.3 billion, as Portman boasted in a 2015 interview.) The office was a small shop when the project was first being drafted, led by Portman and his business partner, H. Griffith Edwards, with freelancers assisting with drafting and rendering. One freelancer, then finishing out a one-year stint in the military at nearby Fort McPherson, was a young Frank Gehry. (Supporting a wife and a young daughter, Gehry needed extra income to supplement his army salary, and he found it by producing Portman’s renderings for the Merchandise Mart.) After the building’s opening, Portman’s entrepreneurial momentum was unceasing.

By 1964 construction had finished on Portman’s own Atlanta home, which he christened Entelechy I, cribbing an Aristotelian term that refers to the “total fulfillment of potential.” (Portman’s second house, Entelechy II, was built on Sea Island, Georgia, in 1986.) The sprawling home was a chance to work free of some of the complexities of his commercial projects, and it became a grand experiment in his budding design sensibility. The building is all but open-air: It reaches out to the surrounding woods with only a thin surround of plate glass holding in the interior. Walking through the home—organized by a grid of hollow columns, six bays wide and four deep—is like experiencing a cinematic montage of walls and floors, greenery and water.

A similar quality animated the 1967 Hyatt Regency Atlanta. This was the debut of the atrium hotel, the innovation that made Portman famous. Entering the hotel from the street, visitors made their way through a dimly lit tunnel before seeing, all at once, the towering skylit atrium above. This reveal came to be known as the building’s “Jesus” moment, after the single word visitors were said to have exclaimed upon seeing the atrium. The first building of its kind in Atlanta, the hotel impressed a palpable, if sometimes startling, sense of urban grandeur. (At the Hyatt, descriptions of Portman’s work as “theatrical” took on a literal meaning, when he moved his offices into the hotel’s defunct Midnight Sun Dinner Theater. The semi-circular stage was transformed into a conference room, with a Portman-authored mural standing in place of the curtain.) Though subsequent renovations have altered the original atrium somewhat, including the removal of the “birdcage” bar, the space remains thrilling. The hotel’s commercial success garnered its architect plenty of opportunities to improve on his model in new projects. Soon Portman’s name would become synonymous with the atrium.

But the popularity of Portman’s buildings did not translate into unanimous critical acclaim. In a 1984 essay, the Marxist cultural critic Fredric Jameson cast the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles as a built encapsulation of late capitalism, a structure whose hermetic and sometimes-confounding interior could, in fact, be anywhere. By the end of the 1980s, the Pritzker Prize–winning architect Rem Koolhaas had characterized Portman’s atrium as “a container of artificiality” and “a device that spread from Atlanta … to the rest of the world.” Even Morris Lapidus, a midcentury architect remembered for his flamboyant hotel designs, conceded in 1978, “There is just too much going on in some of Portman’s interiors.” Still, others saw much to applaud. In 1981 the author and journalist Tom Wolfe approvingly referred to Portman’s hotels as “Babylonian ziggurats” with “thirty-story atriums and hanging gardens and crystal elevators.”

Portman’s son John. C. “Jack” Portman III joined the office in 1973, detailing the design of the Detroit Renaissance Center’s revolving restaurant before working on the Bonaventure. Jack, who now runs Portman & Associates, feels that detractors have missed the point of his father’s work. “Many architects design for the architecture critic, who can get them a good review, but the critic isn’t necessarily the user of the building,” he says. “A lot of the work we did early on is massive, but it’s all focused on human scale. It’s the one thing that is consistent, from the beginning. The basic philosophy is that architecture is an organic creation focused on the needs of the human being.” The firm’s recent projects bear few of the aesthetic markers—scale notwithstanding—that dominated the work of its heyday. Though still operating out of Atlanta, the office is completing new buildings around the world. Grace A. Tan, who joined the office as an intern in 1985 and is now president of the company, sees a continuity between the firm’s past and its present. “Our history is what made us who we are, and it’s the inspiration for what we do now,” she says. “Looking back at all the accomplishments of this firm inspires us to continue to strive, and look forward to what we can do next.”

Today, it’s not unusual for Portman to be celebrated. His architecture, with its vast scale and glittering interiors, offers a radically optimistic vision of the future that resonates deeply in a present time of seemingly unprecedented uncertainty. Jennifer Bonner, an architect and assistant professor of architecture at Harvard, praises Portman’s “pizzazz”—what she calls the architect’s trademark “flair, zest, and sparkle.” For her, Portman is a paragon of tenacity. “As a Southern architect working in Atlanta, Portman quietly invented a new type, the super atrium, without being part of a larger discourse,” she says. “Due to his insistence, a kind of brute force as architect-developer, Portman found a way to experiment with architecture on his own terms. Portman’s architecture is part of a new and different canon.”

For many young architects, Portman’s long career represents a high standard of creative gumption. While a previous generation condemned the joining of architecture and development in a single figure, few millennials are unpersuaded by the monumental products of Portman’s efforts. The wildly original works of this hybrid architect-developer stand in stark contrast to the often-banal and sometimes-destructive creations of unfettered real estate development that are the tradition of modern city-building in the U.S.

Adam Nathaniel Furman, a London-based designer, sees a distinctly American form of determination and beauty at the heart of the work. “Portman’s American vision of beauty is vast, swaggering, vigorous confidence,” Furman says. “It is an incredible belief in the future, that everything is going to be better, everything is going to be bigger, and everything is going to be spectacular. I hope that America produces more architects that represent it in the way that Portman did.”

You may also enjoy “Carol Ross Barney is Chicago’s New Daniel Burnham.”