March 2, 2018

Kenneth Frampton Isn’t Done Changing Architecture

The renowned writer, historian, and teacher has expanded the architectural discipline’s critical and geographic outlook.

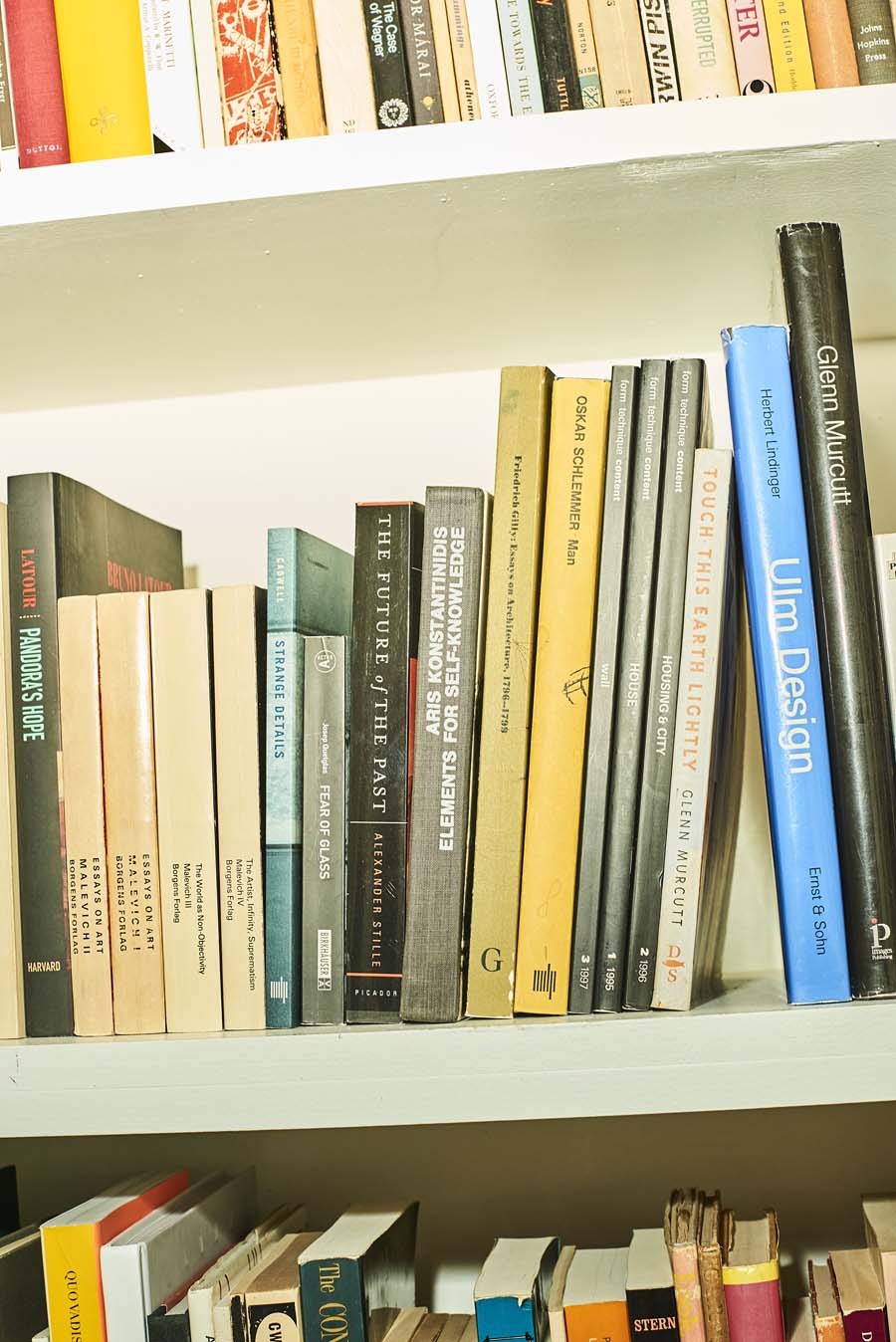

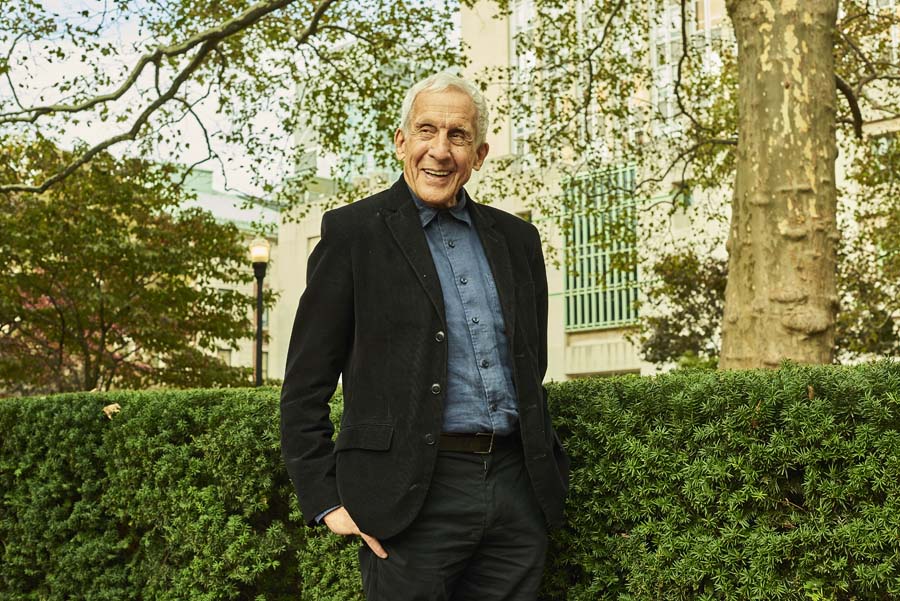

It’s hard to measure the ways Kenneth Frampton has influenced architectural culture. A professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP) since 1972, he has taught survey courses to generations of students (myself included). His seminal 1983 essay “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance” provided a fresh framework for Modernism. And while the 87-year-old scholar has been transferring his archives to the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), Frampton has not stopped teaching or writing: An updated edition of his 1980 book Modern Architecture: A Critical History—a classic—is in the works, with a new chapter that casts a brighter light on architecture practices outside the West.

Zachary Edelson: Before you came to the U.S. from your native U.K. in 1965, you practiced architecture, even designing an eight-story apartment building in London. How did that experience shape you?

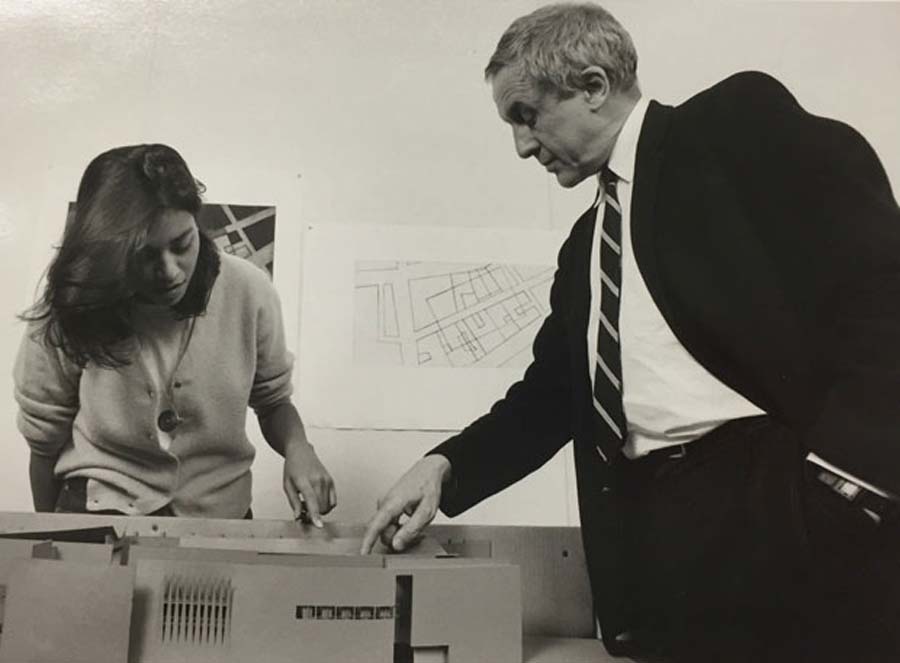

Kenneth Frampton: I was trained as an architect, I worked as an architect. That was my basic formation. I was also technical editor of the British magazine Architectural Design for two and a half years before coming to the States. I was invited to Princeton as a visiting professor by Peter Eisenman. Then I began to teach history, theory, and also design at the same time—more intensely than I ever had before. But this formation as an architect influenced all my academic work and my writing.

ZE: Later, you permanently relocated and participated in the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies [IAUS]. Your second built project was Marcus Garvey Park Village, a low-income, low-rise housing development in Brownsville, Brooklyn. Completed in 1976, it came out of a joint undertaking between the IAUS and New York State’s Urban Development Corporation [UDC]. Looking back, what do you make of that project?

KF: It’s a very complex story because there are many issues involved. One of them is the influence of Oscar Newman and the concept of “defensible space.” That, in large measure, explains this difference between the street blocks and “mews” blocks in Marcus Garvey Park Village.

But maybe the last regret would be that this was the last housing built under the so-called 221d(3) federal legislation, where developers would be subsidized to build affordable housing with low interest rates. That whole program was canceled by Nixon; that was the end of a great deal of public housing in the United States. The whole of Brownsville was and still is ripe for a certain amount of redevelopment. In a different kind of society, what was produced for Brownsville by the institute and the UDC could be seen as a prototype.

ZE: And what about the IAUS?

KF: The institute was an unbelievable place. It was incredibly alive, very productive. Looking back, I can’t believe that we were able to publish the magazine Oppositions and also run these special kinds of preliminary architectural programs for liberal arts colleges on the East Coast, while organizing exhibitions and lectures and producing catalogs.

Then, of course, eventually working on Marcus Garvey Park Village—all of that happened over a relatively short period of time. It wasn’t even a decade in the end.

ZE: What would you say your role was in shaping Oppositions?

KF: I was a founding editor of it with Peter Eisenman and Mario Gandelsonas, and later Tony Vidler, Diana Agrest, and Kurt Forster joined. I introduced a certain thematic to the magazine. The two main Le Corbusier–themed issues were directly edited by me. Certain political or cultural political themes were developed by me, partly Marxist and partly the opposite Heideggerian tradition. This interest of mine in Heidegger occurs first in the magazine, and it’s a relatively early declaration of interest in Heidegger on the part of an architect.

Metropolis Magazine interviewed Frampton in his GSAPP office.

ZE: Let’s talk about “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” your influential 1983 essay. How did it come about? Alex Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre had coined the term “critical regionalism” a couple of years earlier in the essay “The Grid and the Pathway.”

KF: They are definitely the source of the term. I knew the Greek architects who they are alluding to in that essay of theirs, Dimitris Pikionis and Aris Konstantinidis. They exemplified, at the time they wrote the article, the idea of critical regionalism. That’s one source. The other influence is without question the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur, who [in the essay “Universal Civilization and National Cultures”] defines a universal civilization as universal technology and cultures—in distinction to civilization—as the ethical and mythical nucleus of mankind. That distinction between culture and civilization was a key to the article on critical regionalism. [Ricoeur] says it has to be accepted that not all cultures will be able to withstand the impact of universal civilization. I think that’s evidently the case.

“Towards a Critical Regionalism” is really an attempt to formulate a kind of alternative modernity in the face of the advent of postmodernity. I think it’s interesting to distinguish between Postmodern style and the Postmodern condition. Critical regionalism, in that sense, was accepting the Postmodern condition but not the Postmodern semiographic stylistic game.

ZE: Some would say that critical regionalism was your most singular contribution. Do you feel that that’s true?

KF: It does seem to have had a very wide impact. It’s a long time ago, 1983. It’s still referenced, not so much in the Anglo-American world, but in Latin America and to some extent in Southeast Asia and China. That almost speaks for itself, in a way. The answer would be yes, I suppose.

ZE: If it’s still a reference, do you think its manner of dealing with these themes holds up?

KF: Yes, and there’s also an aspect to it that is implied, but not fully elaborated. There’s a political idea, which has to do with direct democracy. I still think that that has a certain validity. The United States is simply altogether too big, and the Electoral College system produces very demagogic results. Some measure of direct democracy could be more beneficial to the species. I’m thinking in particular of the Swiss cantonal system. That’s not explicitly articulated but rather implied in critical regionalism.

ZE: Faced with the rise of ethnic nationalism in America today, do architects have a role in responding to that?

KF: All education really should have that dimension of training to it. The student should be able to practice a profession, craft, or skill that is of use to society. At the same time, it seems to me that all education should have a more generic aspect—it’s very corny to say, but educational citizenship. Besides providing a concrete way of earning a living, it should have that other dimension. I don’t really believe that it’s possible to [position] an architect as a public intellectual or a public servant without [their] having some kind of political position.

ZE: I’m going to switch back to history a little bit. I understand that you spent some time in Richard Meier’s office. Is that true?

KF: Yes, rather absurdly. I spent more or less the length of a sabbatical in that office. That was very much a kind of a second midlife crisis, which I still have. I’ve contributed as a teacher, writer, et cetera, but whether that was the right use of my life is another matter. I never did quite overcome the nostalgia for working as an architect.

ZE: You’ve never been shy about showing support for practicing architects, which is not something all historians do. Are there any contemporary practices whose work you find particularly promising?

KF: There are many, many contemporary practices that are promising. If one keeps one’s eyes very wide open, they’re all over the place. I’m particularly struck by certain architects in Bangladesh and India— above all, Marina Tabassum and Kashef Chowdhury and Rafiq Azam in Dhaka, or Rahul Mehrotra in Mumbai, and also Bijoy Jain. They are extremely talented architects, and they’ve done remarkable work. If one looks for examples at the Aga Khan Awards, one realizes that there’s a lot of talent all over the place producing very interesting modern work. The tendency is for places like New York to suffer from the illusion that they are the center of the world.

ZE: Speaking of things leaving New York, you’re transferring your archive to the CCA. What exactly is in the archive, and how do you hope it will be used?

KF: What exactly is in the archive is the most difficult part of that question. It’s all sort of teaching material, correspondence, maybe some images and drawings. I suppose at some point it could be used if anyone ever wants to write a more detached history of the IAUS, for example. It was used by Kim Förster, a Swiss-German curator working in the CCA who recently put together an exhibition on my teaching.

KF: Peter Eisenman’s archive is there, of course, and so are many other colleagues’. James Stirling’s and Álvaro Siza’s archives are there, so it seemed like a reasonable place to put it. Then Mirko Zardini, who is the director of the CCA, developed an interest in it, so it was a two-way decision.

ZE: Are you working on a new edition of Modern Architecture: A Critical History?

KF: I am. It’s a pleasure and pain together, of course. I’m going to add a fourth part, which will have the slightly simplistic and perhaps preposterous title of “World Architecture.” It will be divided into continents and subsets of those continents. It’s preposterous, but I’m happy to do it to take the book out of its current Eurocentric cast. My approach is, in all the non-Eurocentric cases, to discuss the beginning of the Modern movement in each of these places and then pass from a discussion of that to evidence of the continuation of the movement in the recent past.

ZE: Do you have any other thoughts about the direction of architectural theory or scholarship today?

KF: It’s an issue of tradition. As you know, Columbia acquired the Frank Lloyd Wright archive. The irony is that recently second-year students were taken to Chicago on a trip lasting one week and organized by the faculty of this school [GSAPP]. A visit to any work by Wright was completely absent. That strikes me as very perverse. It’s not that I’m looking for people to do neo-Wrightian buildings. That’s not the point. Scholarship, criticism, and theory need to focus on the material legacy. That’s still what they should do.

Kenneth Frampton is one of Metropolis’s 2018 Game Changers—read about the others here.