April 6, 2018

Pacific Northwest Design: Emily Carr University’s New Digs Look to the Future While Respecting the Past

The new facility in Vancouver, designed by Diamond Schmitt Architects, includes light-filled studio, exhibition, and performance spaces.

For its March 2018 issue, Metropolis Magazine explored the three great North American design regions: The Pacific Northwest, North Carolina, and Minnesota. We looked at each area’s deep historic connections to architecture and design, as well as the contemporary practices thriving there today. Find all our March 2018 North American design articles here!

The pristine, well-resolved shell of Emily Carr University of Art + Design’s new building in Vancouver belies the project’s convoluted backstory. Diamond Schmitt Architects had been thrilled when several years earlier it had won a high-profile competition to design a campus for Canada’s top art school. But elation turned to shock after administrators suddenly scrapped the plans. “I remember walking out of the meeting where [university president Ron Burnett] was saying, ‘So park all of that. In fact, get rid of it. We want to start again,’” recalls Donald Schmitt, principal of his namesake Toronto-based firm. “It seemed painful at the time, but I honestly think we got a better result for it. I have a few white hairs as a result.”

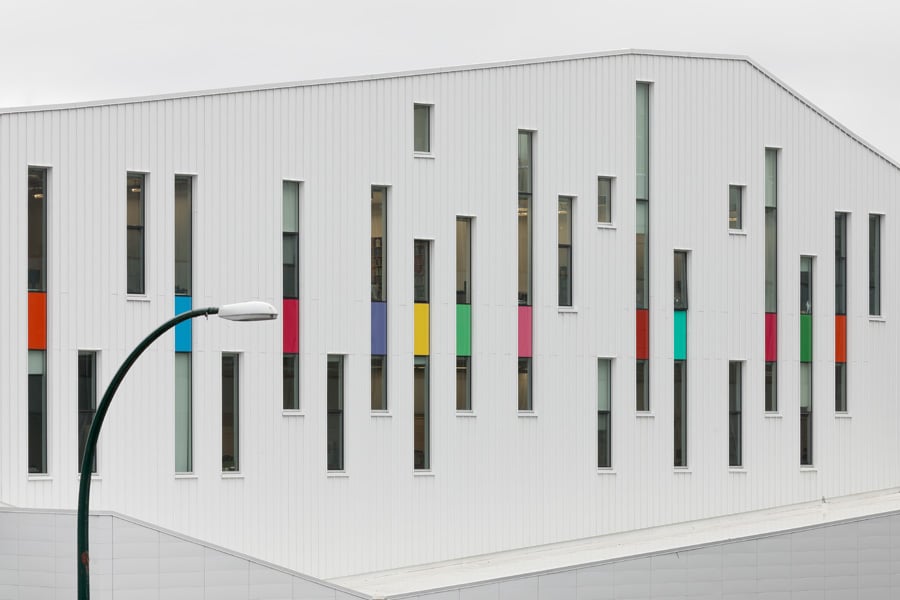

It is hard to see how the architects could have fared better. The $123 million, 290,000-square-foot building (actually, several buildings within a building) in a formerly industrial corner of Vancouver replaces Emily Carr’s smaller, aged-out campus on Granville Island. Its white metal cladding imparts a certain glow or luster, confidently challenging the notoriously gray and overcast local weather. The city’s majestic, varied topographical beauty—a particular source of pride for its residents—is highlighted by huge windows throughout the four-story complex, which bring in views of nearby mountain peaks and natural light for the school’s many purpose-built studios, classrooms, and meeting rooms.

The campus spaces are finely, even obsessively tailored to the activities they host. “Every kind of material and technique is really accommodated, and they all have different functional, power, and safety requirements,” Schmitt sums up. Concentrated on the top two floors are generous work areas for traditional media (painting, drawing, sculpture), while shops for wood- and metalworking, in addition to ceramic kilns, are grouped on the ground floor. The most surprising—and, for Schmitt, exciting—feature is the motion-capture studio, which is wired with 30 cameras and can be rented out.

The building is public-facing, with multiple points of entry that invite the community inside. Fully accessible amenities predominate on the bottom two floors, where Diamond Schmitt placed particular attention on a double- height library and the Aboriginal Gathering Place dedicated to indigenous art programming. Exhibition spaces, a cafeteria, and a 400-seat auditorium round out this public concourse.

Place-based specificities led the way in conceiving the design, Schmitt says. For example, a dearth of public space in the area prompted the architects to situate two plazas at the foot of the building. But in British Columbia, where roughly 5 percent of the population is of indigenous descent, any emphasis on “place” must also take into account the region’s rich, revered, and fraught indigenous legacy. Nods to this history abound in the architecture. The highly visible Aboriginal Gathering Place described above is “front and center on the main public level,” Schmitt says. He also calls attention to several carved cedar bas-reliefs (some executed by indigenous artists; others CNC-milled) placed at key junctures in the school. “That thread of indigeneity is very powerful in the building.”

Emily Carr’s arrival in Great Northern Way, an ex–industrial neighborhood in eastern Vancouver, has ignited a “regenerative spark,” Schmitt says. But there are concerns that this might come at the expense of local character. Adele Weder, the Vancouver-based editor of Canadian Architect, points to a controversial municipal plan to expropriate and raze two adjacent art galleries. “Those are the kinds of neighbors that feed the hearts and minds of the students,” she says.

Certainly, questions of gentrification can’t be ignored. Should they be, Emily Carr University’s striking and sensitively designed new campus may simply bear out architecture’s all-too-frequent aloof- ness when it comes to matters of inner- city overdevelopment. But Diamond Schmitt, through its thoughtful integration of public amenities here, seems sincere in its efforts to set the university up to be a good neighbor.