June 5, 2018

The Smithsons’ Robin Hood Gardens Becomes a Cautionary Tale at the Venice Architecture Biennale

A Ruin in Reverse raises questions about the future of social housing in London and marks the loss of genuine free space

In the neoliberal city, flux reigns supreme. Property is a ladder to be climbed; a home is to be bought and sold; public space is a device for commercial consumption and expenditure.

Nowhere is this more visible than in Poplar, East London, where Robin Hood Gardens, is being demolished. Designed by architects Peter and Alison Smithson in the late 1960s and completed in 1972, the state-built, Brutalist social housing complex once accommodated 252 homes. The site is now being privately developed with a “future regeneration” scheme whose 1,575 homes are being marketed to international buyers as a “high-yielding investment.”

In light of this, the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London has acquired a section of the architecturally renowned estate. The fragment is currently being shown at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale at the Pavilion of Applied Arts in the Arsenale.

The exhibition’s title, Robin Hood Gardens: A Ruin in Reverse, recalls the Smithsons’ contribution to the 1976 Venice Architecture Biennale—a massive poster depicting the project—which they prefaced with the quote, “A building under assembly is a ruin in reverse.” Now an actual ruin of their building sits outside on the banks of a Venetian canal, overlooking Italian Navy docks and a concrete bunker. The fragment is accompanied by a film from Korean artist, Do Ho Suh, which was shot in and around Robin Hood Gardens. Serving as a prelude to the section outside, the film is projected onto a massive 42-by-14-foot screen inside a dark, column-filled room. The impact is overwhelming. Such is the scale of the projection, the room’s dilapidated brick columns get in away and viewers must stand so close they need to turn their head to take it all in.

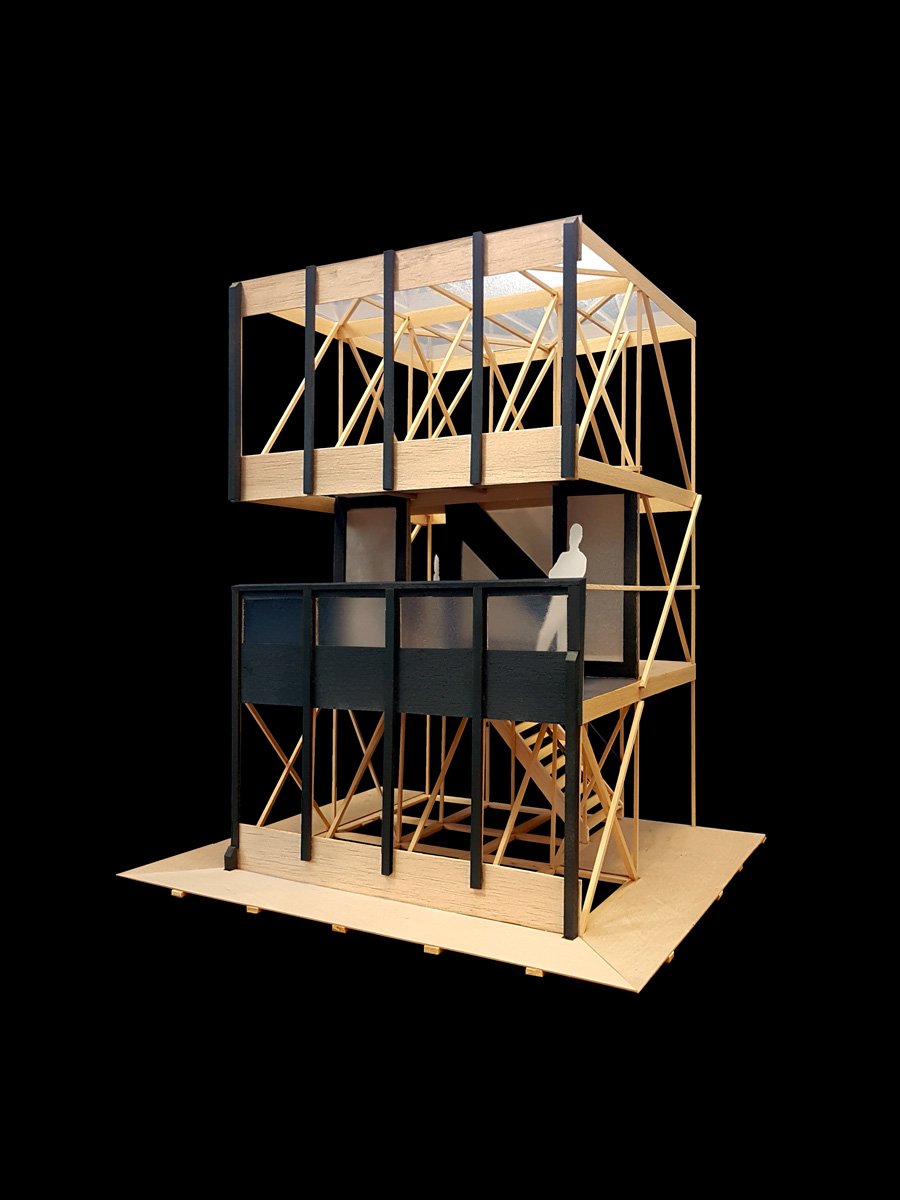

Less overwhelming is the piece of Robin Hood Gardens itself. Propped up by timber board and scaffolding engineered by Arup, only meager elements of the facade are on show, though you can walk up the original stairs complete with an original handrail.

Suh’s film, meanwhile, like London’s East End, is also all about flux. Made using drones, time lapse cameras, and 3D scanners, the camera is continually panning, up, down, left, or right, along the facade. Viewers’ eyes scan across rhythmic patterns of concrete facade details then delve through window curtains to see messy rooms, and toiletry items in bathroom cupboards.

Such movement is irresistible, much like the invisible force of gentrification. Indeed, Suh makes the latter very apparent with a time-lapse shot that, when panning up through an inhabited room, uses an open window to frame demolition teams tearing down a different part of Robin Hood Gardens.

The audience here comes to the realization that many who still live in the remaining block are seeing their neighbors homes torn down, with the traumatic knowledge that theirs is next. “The film touches many emotional elements,” Suh tells Metropolis. “I became more and more aware of the energy that has been accumulated in the space. I tried to capture that.”

There was a danger of this exhibition fetishizing Britain’s working class, with the V&A letting the creative elite descend on Venice to see how the poor people of East London once lived. To see suits sipping prosecco on the section’s balcony did seem slightly perverse. These questions will reappear if and when the V&A exhibits the fragment.

Back in Venice, information on Robin Hood Gardens’ history and Suh’s film mitigate some classist voyeurism. Suh was concerned with creating a piece that “complements the physical building,” while Olivia Horsfall Turner, who organized the exhibition with fellow V&A curator Christopher Turner, wanted A Ruin in Reverse to raise questions about what social housing means today. “So many council housing estates from the ’60s and ’70s that are slated for demolition and redevelopment,” she says. “What kind of a city are we building? What role does properly affordable housing have in that city?”

In the context of the Biennale—whose theme is Freespace—the installation sounds a warning. Images in A Ruin in Reverse reveal the stark proximity of Robin Hood Gardens to London’s financial center. Known as Canary Wharf, it’s filled with glass skyscrapers which sprouted when the Thatcher government designated the area a “Free Enterprise Zone” in the 1980s. (The zones were the brainchild of British planner, Peter Hall, who intended to create a “Hong Kong style free-for-all type areas” in London.) Now almost ten acres of that area are privately owned public space, the antithesis of truly free space. Perhaps then, the Smithson’s housing scheme, with its central green mound, was a Brutalist bastion of this concept. However, consigned as a museum piece, its battle for free space has been lost.

You might also like, “‘Freespace’ Shows That Architects Must Retool Their Relationship to Power—and to the Biennale.”