January 3, 2013

Size Doesn’t Trump All With Phaidon’s “Atlas of Architecture”

Phaidon’s Atlas of Architecture is both extensive and comprehensive

The largest book I own is the 20th Century World Architecture: The Phaidon Atlas. It’s 13.5 by 22 inches. Amazon indicates that its shipping weight is 18.2 pounds. The cardboard carrying case with handles helps. So yes, that’s a lot of architecture. “The most outstanding works of architecture built between 1900 ad 1999” means 757 buildings to the publisher, though some of your favorite buildings may be missing. But you get the distinct sense that if Phaidon had produced a more comprehensive volume the world may have run out of paper.

Those on offer are, of course, excellent. Any comment about the selections is simply going to layer my cherry picking on top of that of the “expert industry panel with input from over 150 specialist advisors from every geographic region” that determined the book’s contents. So before getting to that part of the orchard, an overview.

One interesting conceit is that all of the buildings in the book are still extant (find your Imperial Hotel in some other book) and even accompanied by coordinates of longitude and latitude, which might be practically useful if you happen to have a GPS and a native porter for carrying the book. The buildings within are organized by regional groupings whose representation plays out around the way that these things normally do: about half of them are European, although more frequently unnoticed architectural continents aren’t quite glossed over. There are 72 pages on South America and 52 in Africa. The atlas doesn’t stop at that. Each subsection includes a breakdown of projects by local as opposed to foreign architects, which largely displays the ebbing of European global design hegemony.

Additional early charts illustrate the movements of architects: There’s of course an influx to the US and the UK in the 1930s and ’40s, but otherwise a riot of lines of intriguing origin and destination. It’s difficult to detect a curatorial bias in terms of styles or years. Europe’s strongest decade was the 1930s. North America and Africa boast the largest relative number of buildings from the 1950s and ’60s. Asia shows the greatest comparative strength in the 1980s. Aalto, Breuer, Le Corbusier, Mendelsohn, Mies, and Wright lead the pack in individual selections represented; no surprise there. Some entries stretch beyond the linear “building”. New Delhi and Brasilia are represented along with a few master plans that seem worthy of recognition even if their constituent structures had varied designers, such as Potsdamner Platz in Berlin or EUR in Rome. It’s difficult to argue with these grand inclusions on any categorical ground.

I don’t know which of the images in this book “have not been published for over 50 years,” but I’ve certainly never seen many of them. Following Soviet architecture closely, I had never heard about “Latvian National Romanticism,” the elegant Romanov Bazaar Complex, or its architect Eizens Laube. Neither was I familiar with the fanciful Art Nouveau residence for Russian Railway Staff in Harbin, China (designer unknown). Nor did I know about the Nedbank building in Durban, in which satisfying Modernist geometry is achieved with the most unlikely of objects—a hollow brick lattice. Or the captivating relief murals of the Bank of Guatamela that occupies two full sides of the building save for two window bands. And so on.

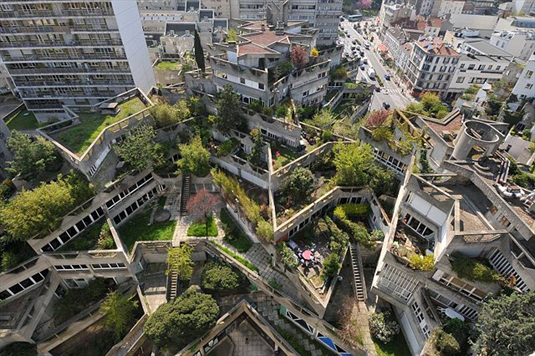

There’s the dazzling Phnomh Penh market, with cruciform wings rising one roof terrace after another, to a central dome. Or Henri Van De Velde’s University of Ghent Library, whose blocky concrete mass is balanced by three pinstripes of window columns and topped by a set-back glass pavilion. Or Oud’s Kiefhoek Housing Estate, which proved that the terms “streamline” and “housing estate” need not exist in perpetual animosity. Or Jean Renaudie’s Les Etoiles redevelopment in Givors, France; John Johansen once wrote about a project’s aim to let a “hill determine the organization and character and life of the project.” Renaudie, by means of a variety of lushly planted terraces and bridges, simply made his nine-block whole seem to become the very hill. Sachio Otani’s Kyoto International Conference Hall, eschewing any vertical walls or columns to achieve internal spaciousness, while its exterior nodded to traditional Japanese roofing.

There are other delights of incongruous proximity. The Georgian ministry of Highways stands next to the Kuwait Towers. Albert Speer faces James Stirling, and Louis Sullivan nestles next to Marcel Breuer. Most importantly, these selections are united by superb photography. Ezra Stoller did not photograph every modern building on earth but given the quality of selections within the book you’d be tempted to think he did. I’d been on something of a tear looking for photos of the Lenin Museum in Uzbekistan. Suddenly, there were better photos than all the riches of the internet had yielded. Your favorites, however popular or obscure, will be frequently depicted in sharp or unexpected detail. The Cinema Impero and Fiat Tagliero buildings in Asmara, Eritrea, are here in angles I’d never before seen. Wide-angle views of the Torres Blancas apartments in Madrid are common but here’s a close view of the base. The ubiquitous angle for photographing the Chilehaus in Hamburg is its prow-like corner; here we have an overdue look at its majestic courtyards. Diagrams, cross-sections, and a variety of site plans make grasping the totality of a building all the easier.

As a rule of thumb, a book that tackles a subject as large as the world and a time span as long as a century in fewer than 800 pages usually seems suspiciously thin to me. Different rules apply to art volumes and yet the Phaidon atlas has still met this challenge. You may require a second coffee table just to hold this architectural survey, but it’d be well worth it.

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn. He has written for The Wall Street Journal, The Awl, Bookforum, City Journal, and The Millions on urban policy, cinema, historic preservation, and literature, and Metropolis on Long Island Modernism, Boston city planning, the preservation of Brutalism, and a variety of other topics.