July 7, 2013

Reclaiming the Lost Lots of Philadelphia

Ariel Vasquez is dedicated to restoring a sense of community to his neighborhood

No matter how many times you hear the oft-bandied statistics about the City of Philadelphia’s 30-40,000 empty lots, the numbers are still staggering. Though it is sobering to witness the immediate devastation of a natural disaster, urban wastelands are the arid result of a more insidious, decades-long process.

What to do?

Philadelphia has yet to gain a handle on its vast inventory of lost opportunity. Jurisdiction is spread across several agencies that it hopes, ultimately, to combine. The unwieldy alliance between the Department of Public Property, the Philadelphia Housing Authority, and the City of Philadelphia itself has stalemated progress.

Ariel Vasquez, trained as an architect (Drexel University, Philadelphia) and urban planner (The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design, Rotterdam), is a college graduate who isn’t waiting around for action. He is dedicated to research, trying to restore a sense of community to his Fairhill neighborhood in Philadelphia as featured in his own “Claiming Places Lab” study “Lost Lots.”

Vasquez maintains that Fairhill, alone, has 2,824 lots that are either flat empty or are remaining sections of derelict properties, half of which he says are owned by the city. Private owners of the other half of those abandoned lots have to, somehow, be individually tracked and accounted for.

Vasquez draws from his own field surveys and open source GIS (Geographical Information Systems) data from the City of Philadelphia. Apparently, the City of Philadelphia categorizes some properties as “in use” despite what Vasquez may consider ruins as he walks the site. The lot count, literally, depends on what your definition of “empty” is, a perfect illustration of the magnitude of the problem.

Vasquez was born in the Dominican Republic. Fairhill was a significant Latino community back in the ’60’s. Fabric and tobacco (cigar rolling) industries were populated with Latino employees.There was a certain social cohesion back then that he wants to reconstitute in some fashion. It wasn’t necessarily the “good old days,” though. Vasquez is pained to say there was racial tension between the established black community and Latino immigrants in competition for employment at the surrounding industries.

“Lost Lots” is based on the premise that the physical space of the city, its organization and quality, can be a mechanism of integration….where a sense of belonging is fostered.

Ariel Vasquez, architectural researcher & urban planner

Photos: Joseph G. Brin

Half a century later, Fairhill is a wide field of large, empty lots and scattered, small clusters of remaining row houses. There are some new developments stirring that represent a glimmer of hope but the scope of the task is daunting. Vasquez says, “I want to do architecture and design on my own terms, to play with conceptuals.” Vasquez works as a construction manager for a firm, seeks commissions with an experimental design collaborative (TRANSforma Studio), and devotes enormous amounts of unpaid time mapping and building a database for his own community.

He’s in no particular hurry. “I want to do it very naively, slowly, to understand the laws and the community,” he emphasizes. Vasquez is taking his academic training to the streets. He once stood on an empty lot with a megaphone talking about site problems and ideas for regeneration. As people from the community walked by he engaged them in a dialog.

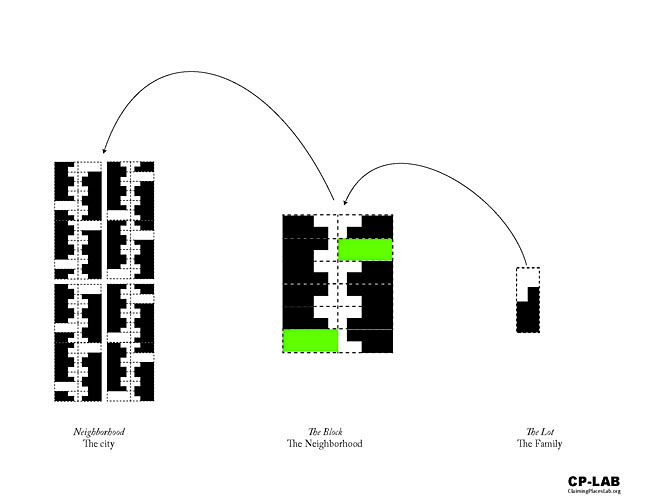

With quiet determination Vasquez is methodically evolving a visual grammar of simple diagrams to extract data and explain possible land use improvements. “My priority is to give back the tools to reclaim these lots,” he adds. The result will be a catalog, a prototypical guidebook for community restoration that could, theoretically, apply to most any city.

Vasquez applies lessons in forensic architecture, working backwards from destruction to construction. Call it urban archeology, if you wish. There are many layers and it requires an aerial perspective to begin to grasp the extent of emptiness. He shows pockmarked housing clusters that could benefit by acquiring empty areas (shown green below) as public zones that neighbors could share and take responsibility for.

In The Last Days of Old Beijing, author Michael Meyer chronicles what life was and what was lost as modern Beijing rushed to demolish many of the courtyards (hutongs) that had unified old residential quarters in that city for centuries. There is a lesson in reverse there as Philadelphia could use a variation of that concept to incrementally restore broken communities marooned in an otherwise densely populated city.

Vasquez talks about Fairhill teenagers expressing a sense of hopelessness. They see no reason to stay. “It’s sad. They don’t see themselves living in the community,” he says, adding they’ve told him they are “tired of the drugs, trash, and loitering.” His commitment remains firm, “This started out as a project for the community and it will end as a project for the community.” Even when the catalog is published after this August, he will continue to build digital resources for Fairhill on the web.

For Vasquez, tilling the fallow soil of the public realm may yield new life so his parched community can grow and thrive once again.

Joseph G. Brin is an architect, fine artist and writer based in Philadelphia.

Graphics courtesy of Claiming Places Lab (CP-LAB) unless otherwise noted.