May 1, 2015

Inside ARTIC, the Polymer Cathedral Connecting Southern California

Bringing eight modes of transportation together was not the only complex problem at the Anaheim Regional Transportation Intermodal Center (ARTIC). The engineering firm BuroHappold worked with HOK, Parsons Brinckerhoff, and Clark Construction not only to build the largest span of ETFE roof cladding in North America, but to also reduce energy and water use by […]

Bringing eight modes of transportation together was not the only complex problem at the Anaheim Regional Transportation Intermodal Center (ARTIC). The engineering firm BuroHappold worked with HOK, Parsons Brinckerhoff, and Clark Construction not only to build the largest span of ETFE roof cladding in North America, but to also reduce energy and water use by 30 percent, and achieve an anticipated LEED Platinum rating.

Courtesy Rick Horn

The future of transportation in Southern California resides 28 miles south of downtown Los Angeles, in the form of a voluminous LED-illuminated carapace that could easily be mistaken for an outpost of the Magic Kingdom situated only a few blocks away. But while Disneyland’s promise of “where dreams come true” is popularly appreciated, the newly opened $185.2 million Anaheim Regional Transportation Intermodal Center (ARTIC) has only just begun realizing its hopes of becoming a world-class gateway, connecting no fewer than seven transit systems (and an eighth on its way, with California finally breaking ground for the construction of the first 29-mile segment of a statewide high-speed rail system), all under a commuter’s cathedral of translucent polymer.

ARTIC’s most notable innovation is its geogrid husk. Composed of opaque pillowed ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE) membranes covering 200,000 square feet, during the day the station interior is awash with light akin to sunlight glowing through rice paper, while at night the building glows discotheque vibrant. At one-tenth the weight of glass, the foil polymer offered project architects HOK and partner BuroHappold Engineering an unconventional and cost-efficient material capable of canopying the 120-foot-tall, three-story project. Inspired by grand terminals of yesterday, the team used ETFE to realize its aesthetic and sustainability goals, constructing what will soon be the world’s first LEED Platinum intermodal transportation center.

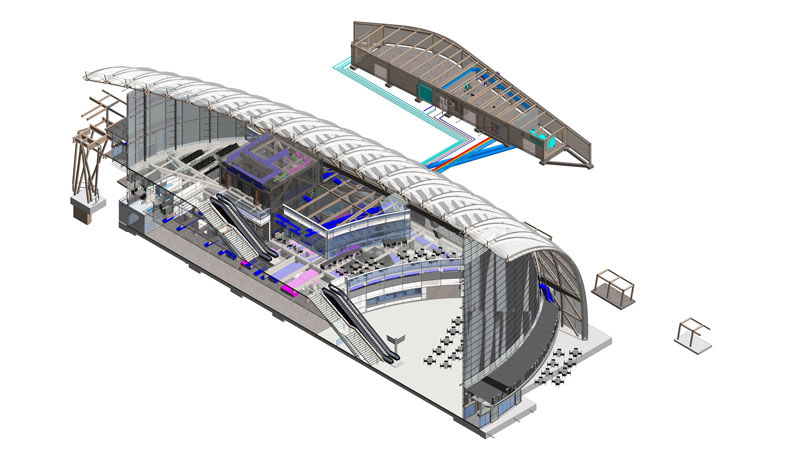

Yet, the decision to clad the 67,000-square-foot facility’s roof enclosure in triple-layered foil pneumatic pillows of ETFE proved deceptively challenging. ARTIC’s architects, engineers, fabricators, and contractors turned to custom building information modeling (BIM) to “design out the risk” before attempting to span what was to be the largest ETFE structure in the United States. “The ETFE roof is not unique in North America,” says David Herd, managing partner of BuroHappold. “Bear in mind that we started the design in 2009, so there are a lot more installations now. But in Southern California, there’s only one other installation of three ETFE pillows, in Pasadena.”

ARTIC connects Amtrak, Metrolink, Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA), Anaheim Resort Transportation (ART), buses such as Coach USA, taxis, bikes, and shuttles. To help make the process of designing these connections more efficient, BuroHappold used a range of digital tools, including 3D modeling in the early stages, digital fabrication, and virtual design and construction with BIM, saving time and money on the project.

Courtesy ARTIC

With 9,500 geometric points pinpointed across the span of 40 symmetrical but unique arches covered in translucent cushioning, and two faceted parabola-shaped glass walls, there was gymnastics galore to navigate. The delusory simplicity of the diamond grid structure revealed itself once the team developed a model using Gehry Technologies’ Digital Project software, which was then translated to Autodesk’s Revit BIM software—the computational application used to populate all of the structural numbers for modeling, and for team coordination and simulations between architects, engineers, and contractors. Custom routines specific to ARTIC’s requirements were integrated into Revit software, eventually resulting in one of Autodesk’s first open-source projects, a visual-programming add-on now known as Dynamo.

The process, BuroHappold’s associate structure engineer Kurt Komraus notes, is truly one of collaboration. “It’s very important with this kind of fast-moving technology that this software gets the support of the community —the worldwide community of architects and geometry nerds who are taking complex buildings and using computational methods in order to document, design, and realize them,” he says. “It takes a village.”

Daylight and solar heat gain were the key environmental considerations on the 16-acre site. The more conventional method of dealing with this was the use of glass curtain walls on the north and south ends of the building (above) —high-transparency facades of up to 120 feet hung from the roof by cables. Operable glass louvres controlled by the central building management system keep the main hall comfortable at all times.

Courtesy Rick Horn