January 20, 2017

NYCHA Finally Acknowledges the Importance of Design—But Is That Enough?

For the first time in its 83-year history, the New York City Housing Authority has released guidelines that establish design principles to follow when rehabilitating residential buildings. But is this a case of too little, too late?

NYCHA buildings in Harlem

Courtesy Guglielmo Mattioli

The New York City Housing Authority released a groundbreaking document last week: new design guidelines for the rehabilitation of residential buildings. According to Jae Shin, an Enterprise Rose Architectural Fellow who led NYCHA’s efforts on the guidelines, they are the Authority’s first real attempt to go beyond just visualizing codes and standards by establishing effective, resident-focused design principles to follow.

By rethinking the way rehabilitation is managed, from just repairing problems to taking a more design-based approach, the guidelines are indeed a milestone in the history of the housing authority. However, the fact that it took 83 years to include design as a key part of residential buildings’ rehabilitation says a lot about the organization’s slow-moving progress. And, unfortunately, the guidelines do little to quicken the pace. Flipping through the pages there are a lot of “designers should” or “designers are encouraged to”—it is not clear when and how designers will “have to” abide by them.

The guidelines are part of a broader strategy from NYCHA to improve its immense building heritage–more than 2,500 buildings across the five boroughs grouped in 328 developments, 84% of which are 30 or more years old. Over the years, the housing authority has often been under fire because of poor maintenance of the units, low levels of safety in its complexes, and lack of units available. Indeed in 2015, councilmember Ritchie Torres and state Senator Jeff Klein went so far as to document the unlivable conditions of many NYCHA buildings in a damning report titled “Worst Landlord in NYC?”

To combat these problems, the housing agency put forth NextGeneration NYCHA, a 10-year strategic plan, and, less than a year later, the 2016 NextGeneration NYCHA Sustainability Agenda, which aims to upgrade and modernize the housing units. The guidelines took one year of extensive talks between the NYCHA Office of Design, the maintenance and operation teams who work on the buildings every day, architects, designers, and non-profits engaged in design and community building.

The guidelines, which act as a kind of reference book for designers, focus primarily on four functional areas of building rehabilitation: site, building exterior, building interior, and mechanical systems. The goal is to support the safety, health and comfort of residents, improve the environmental impact of the aging and inefficient buildings, and use more high-quality and cost-effective design and construction.

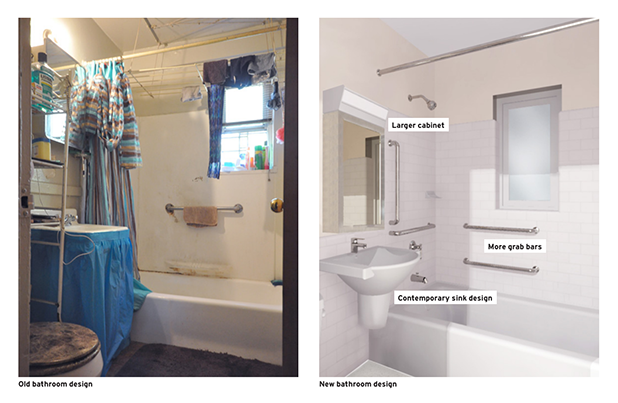

Most of the guidelines are common sense (indeed, the fact they haven’t been followed before now illustrates how dire the situation has been): use healthy materials for spaces where people live, make the buildings more energy efficient, reduce humidity (a huge ongoing issue) with better roofing and cladding of facades, preserve historic units, open up green spaces between buildings, etc. (although, the new bathroom layout ceases to take into account the need to replace bathtubs with more accessible showers).

New vs old bathroom layout

Courtesy Design Guidelines Rehabilitation of NYCHA Residential Buildings

To its credit, the document also gives very specific instructions on how to renovate interiors spaces, such as kitchens and bathrooms, by relaying suggestions from the maintenance and operation teams who have assessed design flaws through their daily work. For example, the guidelines suggest designing new kitchens with cabinets that are easier to inspect and larger back splash panels to prevent water and debris from accumulating behind cabinets and appliances. The interior renovation of bathrooms and kitchens and parapet redesign is slated to start at the Breukelen Houses in Canarsie Brooklyn, and gradually expand to all units.

Other guidelines have also been already put into place, like the installation of new LED lights in the Bushwick Houses in Brooklyn and the Polo Grounds Towers in Harlem; the lights are more efficient, brighter, and increase the perception of safety.

Regarding open spaces, the document recommends removing fences around NYCHA housing in order to better integrate the complexes into their neighborhoods. The redesign of open spaces is pivotal to activating ground floor spaces and incentivizing residents to use the green spaces between buildings. However, the tower-plus-park typology of most NYCHA developments is hard to connect with denser urban fabrics, and NYCHA, an organization that is perennially underfunded, clearly doesn’t have the resources to completely or partially rebuild entire blocks of buildings.

Bottomline, the design guidelines are a step forward in the right direction: they engage with architects and designers and can be a useful resource. However, they are still a collection of suggestions rather than requirements. It will take time before they will be fully implemented, and even when that happens, NYCHA will still have to solve it’s managing and funding issues if it is to provide housing that is affordable, safe, and well designed to those in need.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Navigating the Path to Net Zero