February 13, 2014

Design Students Take on Universal Design

Research at the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design is transforming the practice—and the very definition—of universal design.

Kate Gaudion, a research associate at the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design (pictured left), conducts a study with adults with autism at the Kingwood Trust, to understand how they can be motivated to complete everyday chores for themselves and feel more self-reliant.

All photos courtesy the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design

“You can’t have every product, service, and environment absolutely accessible to everybody,” says Jeremy Myerson, the co-founder and director of The Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design at London’s Royal College of Art (RCA), one of the world’s foremost research centers for design that serves people of all ages and abilities. “Universal design is a vision, but it’s impossible,” he says. Since its founding in 1999, the center’s approach has instead been one of inclusivity, partnering with industries to prove that addressing the abilities and desires of as many people as possible is not only morally (or legally) right, but also sound business practice. “Universal design was driven by legislation,” he says. “Inclusive design is about waving a carrot rather than a stick.”

The center’s origins lie in a 1991 initiative about aging societies, but its projects have expanded to address a much broader range of issues. Research associates, many of them recent graduates of the RCA, work in three labs—Age & Ability, Health & Patient Safety, and Work & City. Projects completed in the last year—some of which are highlighted below—include products for adults with autism, a software program to help caregivers deal with their patients’ bedsores, and furniture that suits convalescents and people who need care, designed for the leading Swedish manufacturer Kinnarps. The center’s take on older citizens, its original focus, has also grown more nuanced. “We are looking at aging, not just from a ramps-and-grab-handles point of view, but from an aspirational point of view,” says Rama Gheerawo, the deputy director of the center, who heads its Age & Ability research lab. “We had this idea we call Edges of Aging, which is looking at things that are not usually considered, like sexuality.”

Over the years, there has been a shift in solutions, from things to ideas. “When we started our research associates program, it was about delivering good design—delivering inclusive design,” says Gheerawo. “Now we find we’re delivering inclusive process.” The center recently conducted workshops for bureaucrats—both with Hong Kong’s Civil Service Bureau and closer to home at 10 Downing Street—on how to design better policy that does not leave out certain citizens.

Created for adults with austism, the Spinny Disc creates a new sensation in a mundane activity. The concept came out of a three-year-long research process.

An upcoming challenge will be the intersection of inclusivity and sustainability. “There are some conflicts and some convergences,” Myerson says. “For people with poor sight, it’s easier to control glare on a computer screen by using artificial light and screening out sunlight. But that then puts an emphasis on energy consumption.” Gheerawo suggests that we might have to retool the metrics. “How do people visualize energy?” he says. “Are we in the land of misinformation, because we’re focusing on technical requirements rather than human requirements?” After all, the grand goal is the same: to ensure that people of all shapes, sizes, and abilities live happy and well-adjusted lives on this planet.

The 2013 Helen Hamlyn Centre research projects

Playful Chores

The idea behind the Hubble Bubble Vacuum Cleaner is not only to simplify the object, but also to offset the displeasing noise with fun bubbles.

Feeling like a grown-up, and in control of one’s life, is surprisingly dependent upon the little things, like doing laundry or cooking a meal. We take these everyday activities for granted, but the coordination, dexterity, planning, and communication skills required can be challenging for someone on the autism spectrum. Building on her previous work in the field, Katie Gaudion found ways for Kingwood Trust, a key service provider for people with autism, to motivate adults using sensory incentives.

After a year of research, she developed two engaging products—a vacuum cleaner that blows bubbles, and a colorful wheel that can make laundry fun. But more importantly, she defined four key design principles to encourage people with autism to manage their own lives and homes: extend their sensations (if someone likes how washing machines spin, say, they might like salad spinners); tailor activities to their needs (finding less objectionable ways for people to complete tasks they don’t enjoy); embrace their choices (let people do things their way, rather than forcing them to conform); and create novel experiences (add entertaining elements, like sounds or shapes, to boring activities).

Wellness Update

As part of the “The Qualified Self” project, research associate Peter Ziegler joined the fitness routine of an older person in Hyde Park, London.

Smart solutions for health care these days tend to focus on younger people, “digital natives” who are used to thinking of well-being in terms of numbers such as body fat, heart rate, steps taken, or calories eaten—a perception known as the “Quantified Self.” Working with the leading Japanese electronics manufacturer Panasonic (which caters to a sizable aging population back home), Peter Ziegler conducted an in-depth study of 24 users, focusing on how technology can be customized to help older people—who are less interested in wearing smart gadgets and reading graphs on an app—stay healthy and happy. He designed a system called the Qualified Self, which identifies emotional and aspirational aspects that can be used along with numerical data to give older people a more well-rounded understanding of their health.

Message Delivery

Research associate Tom Stables studied how a wide array of users, of all ages and abilities, put on, maintained, and stored their hearing aids.

The Danish company Oticon was one of the first to develop and popularize hearing aids, more than a hundred years ago, and today offers a mindboggling array of state-of-the-art products. But it faces a significant challenge—hearing aids are often misunderstood, misused, and then rejected by users who could really benefit from them. During his two-year study, Tom Stables identified two targets for the company. Firstly, the basic functions—such as putting on a hearing aid, changing the battery, cleaning, and storage—had to be streamlined. Secondly, where the functions are hard to simplify through design, instructions had to be explained in a simple way. This sounds logical, but is extremely complex to implement in real-world scenarios with diverse users. To address this challenge, Stables developed sophisticated research tools and design methods, which are being incorporated into product development at Oticon.

Caring Chairs

Johansson’s designs for care furniture include a table, supportive dining chair, and sound-channeling conversation chairs (above).

Furniture companies in Scandinavia, as in many other places in the world, increasingly have to adapt to the needs of an aging population—a significant portion of whom are assisted or need care. Lisa Johansson conducted research with older people, and their friends, families, and care-givers in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, and generated a framework to guide new product development at the Swedish manufacturer Kinnarps. She also helped create four concept designs: a modular lounger that can be adjusted without any assistance; a tray/side table that has a chargeable top, so that older users need never lose digital connectivity after forgetting to charge their devices; a dining chair that helps users stand up and sit down easily; and a semi-cocooned conversation chair that amplifies sound for people who are hard of hearing.

Resting Easy

To find a solution for bedsores, the researchers studied many aspects of the problem, including pressure areas on the body (above) and complicated caregiver practices.

The problem that Gianpaolo Fusari and Jonathan West took on was well-known but unresolved in patient care—bedsores. Properly called pressure ulcers, these can sometimes cause permanent disabilities. The solutions seem simple—stay dry and change positions regularly—but the problem persists. In 2004, more than one in ten residents in a U.S. nursing home had bedsores. In the U.K., four percent of the National Health Service’s annual budget is spent treating pressure ulcers. At a systems level, the team developed a new approach to monitoring and caring for people. They also explored new surfaces and products to relieve pressure on the body, and developed a software program to help caregivers keep better track of their patients.

Sticking with It

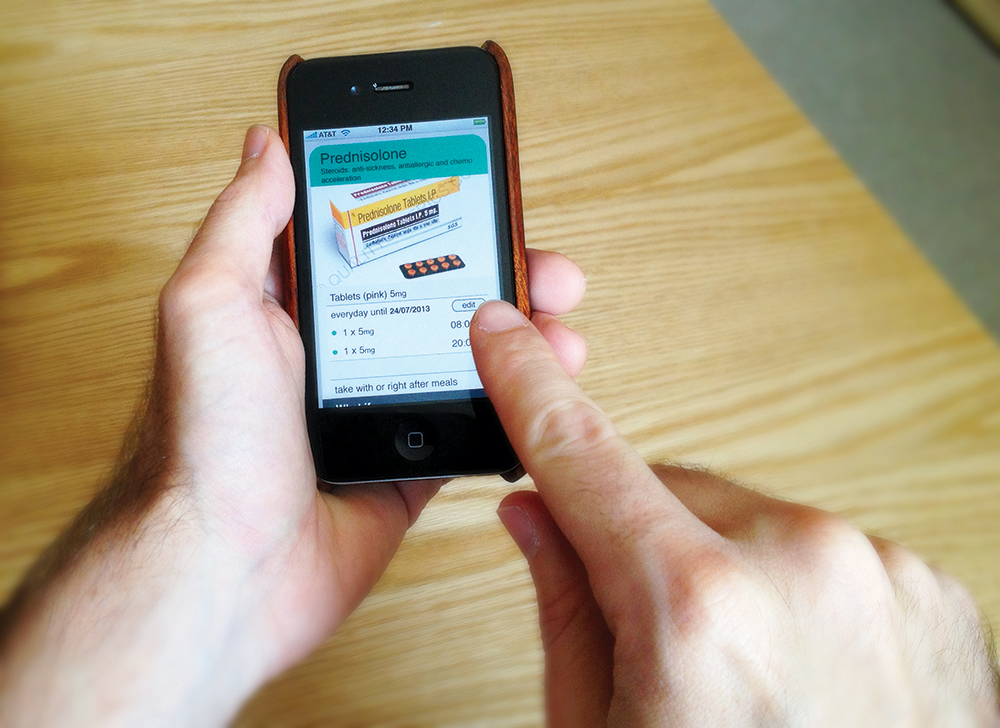

This project used fakes pills to understand how breast cancer patients deal with unfamiliar medication regimens. One outcome of the project was a smartphone app to help patients manage their dosage.

To say that grappling with breast cancer changes one’s life would be a gross understatement. Maximo Riadigos and Jonathan West took a deep dive into the challenges that people face while undergoing treatment and found a significant concern: Many people learn about their complicated medication regimen during one session with a nurse, usually after chemotherapy, when they are stressed and find it hard to concentrate. Relying on some rather innovative methods to gain insights—for instance, fake blister packs were used much like placebos are used in drug trials, to understand responses to unfamiliar drugs—the researchers developed a smartphone app to support patients, both during the session with the nurse as well as at home.