July 18, 2017

Frank Lloyd Wright on American Democracy’s Potential for “Mobocracy”

A new book, edited by Kenneth Frampton, collects Wright’s prolific writings, including various political musings on the potential for Americans to lose their freedoms.

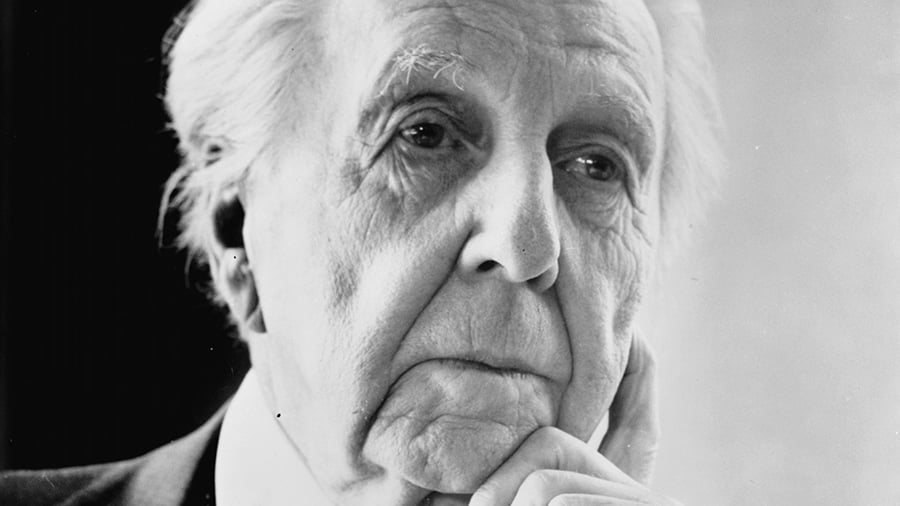

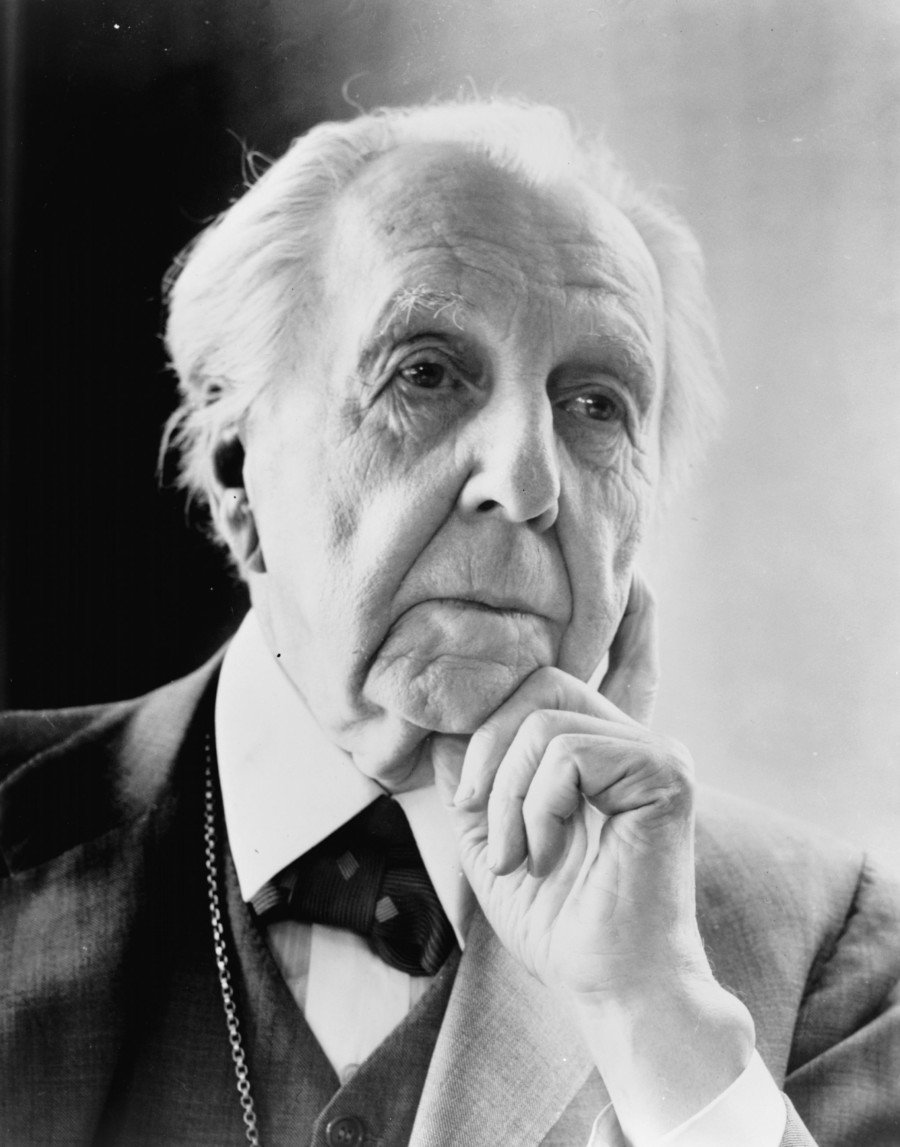

Talk politics with any architect long enough and you’ll likely find them hard to pin down. Radical by many measures, traditional in their own ways too. The 20th century’s most prolific and civic-minded American architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, was no different.

Though in many ways he was proud and optimistic about America, often quoting Ralph Waldo Emerson in soaring descriptions of the nation’s vast treasures and potential, Wright had some serious concerns about his homeland, too. It’s a fascinating exercise to look back at what Wright wrote—over more than six decades—about the health of America’s democracy.

This month, Columbia Books on Architecture and the City is releasing a collection of essays by historian Kenneth Frampton all about the famed architect’s written works. In Wright’s Writings: Reflections on Culture and Politics 1894-1959, Frampton writes that “Wright believed, as few have either before or since, that architecture was a crusade on the behalf of human civilization rather than a mere profession.” There’s ample proof of that zeal here, both in quoted material and the reproductions of Wright’s letters, speech drafts, articles, and broadsheets from Columbia University’s Avery Library archives.

Frampton writes that Wright held to a Midwestern provincialism throughout his career while adopting what could be perceived as dissenting positions. Wright, after all, expressed his public admiration of Japanese and German design cultures even during wartime. He visited the Soviet Union with his third wife, who was Russian, and took supportive stances toward its revolution’s ideals, even though he expressed concerns about artistic freedom and social justice there. It’s not a surprise, then, that Senator Joseph McCarthy labeled him a Communist.

Turning to his own country, Wright “chided the American public for their political immaturity,” writes Frampton, and worried—especially in the aftermath of the Great Depression—that “capitalism had reached an impasse and that only a fundamental change would enable the United States to restructure itself and recover its former energy and direction.” Though the architect was never super-clear about political solutions, he was leaning toward what Frampton describes as “some kind of neo-capitalist social democracy.” Quite a synthesis, indeed.

Communism and Fascism were world-shaking movements that had to be taken seriously by thinkers of Wright’s day, and he did so accordingly. He even dared to criticize capitalism (or aspects of it), not a tactic many architects working today would willingly adopt. Yet more than any of these political “isms,” Wright wrote compellingly about democracy, its challenges, and the need for its constant maintenance and revitalization. Here’s a taste of his thoughts on the subject.

Wright was concerned that the American public—which he sometimes called a “mobocracy”—wasn’t educated or willing enough to stay active in shaping its own government and culture.

“It is true that the educational system of the country has for many decades been breeding inertia.” —letter to Moissaye Olgin, the American correspondent for the Moscow newspaper Pravda (1933)

“But we have been on our own, a civilization professing Democracy (and practicing nearly everything else) for a long time now. Since 1776 to be exact. . . . A witty Frenchman said of us “the only great notion to have proceeded directly from barbarism to degeneracy with no culture of its own in between.” —“Of Thee I Sing,” first published in Shelter magazine (1932)

“Do they know what democracy means? Ask them and weep…We as citizens have only ourselves to blame for these losses politically, educationally, yes and morally.” —“Wake Up, Wisconsin,” published in the The Capital Times (1952)

He sounded an alarm about American politicians using messages of fear as a political tactic, for economic gain.

“Fear is the real danger in any democracy. Our worst enemy now is this craven fear managed by conscienceless politicians. Scare the mob! . . . We are victim of moral cowards putting up a sham fight. . . . What great State has not been eventually ruined by the ‘patriotism’ of conscienceless public-servants? History has no conflict on this point. All have died of exploited FEAR.” —“Wake Up, Wisconsin” (1952)

He warned of an Executive Branch overstepping into autocracy, with help from the media.

“With this elected president cheerfully making a role for himself never intended for the president of this republic, in any circumstances whatsoever, the role of ruler, we the people of this country, unable to see clearly, are sinking deeper into fatal coma—we are less and less able to recognize ourselves as a free, independent nation. Instead of an honest forthright independence, all we know is what we read in the papers and all the papers know is what they think is good for the people to known in the circumstances. We are now dependents in order that a “ruler” may make a bid for world-power and for commercial-supremacy. Both were, and always will be, a despot’s mirage.” —“Usonia, Usonia South and New England,”Taliesin Square-Paper (1941)

He believed that individual freedom, creativity, and expression (even in technology and “the machine”) were American democracy’s best chance.

“The machine does not write the doom of liberty, but is waiting at man’s hand as a peerless tool, for him to use, to put a foundation beneath a genuine democracy.” —from his first Kahn Lecture in the 1930s

“The only safe-guard Democracy can have is a free, morally enlightened fearless minority.” —“Wake Up America!” (1940)

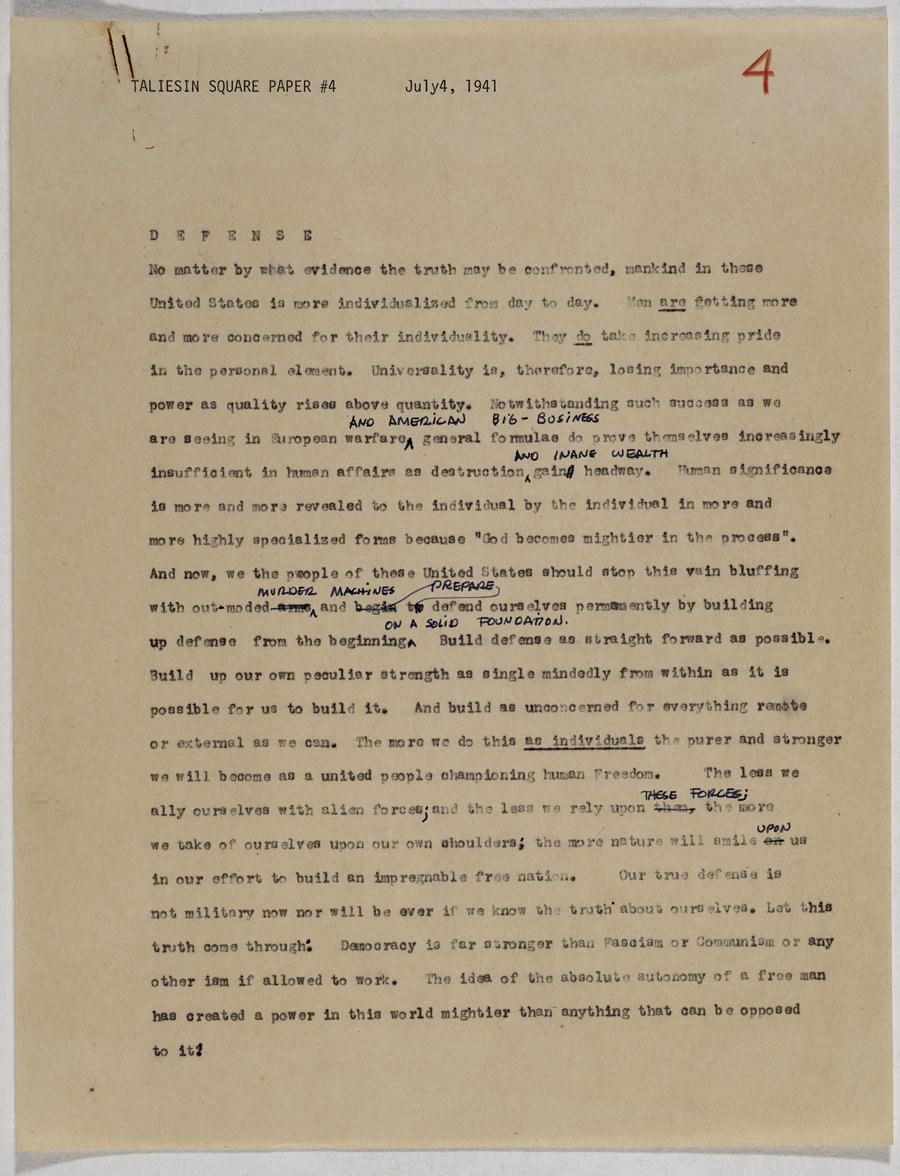

“Let this truth come through: Democracy is far stronger than Fascism or Communism or any other ism if allowed to work. The idea of the absolute autonomy of a free man has created a power in this world mightier than anything that can be opposed to it.” —“Defense,” Taliesin Square Paper #4 (1941)