November 20, 2015

Susan S. Szenasy Ponders the Future of Paper Archives

“In our mad dash into the digital world, what happens to our nondigital history?”

At Metropolis, we’re starting to settle into our new sunlit offices in midtown Manhattan. Our digs are taking shape as the furniture arrives and books and magazines find their places on our shelves. We are trying to figure out how the paradigm of the digital office, with its emphasis on minimal physical artifacts, will work for us. But much of our effort is focused on making a physical object. Our great, open room is now the shop floor where writers, editors, fact-checkers, proofreaders, designers, sales reps, and marketing and production managers are working to meet the printer’s deadline.

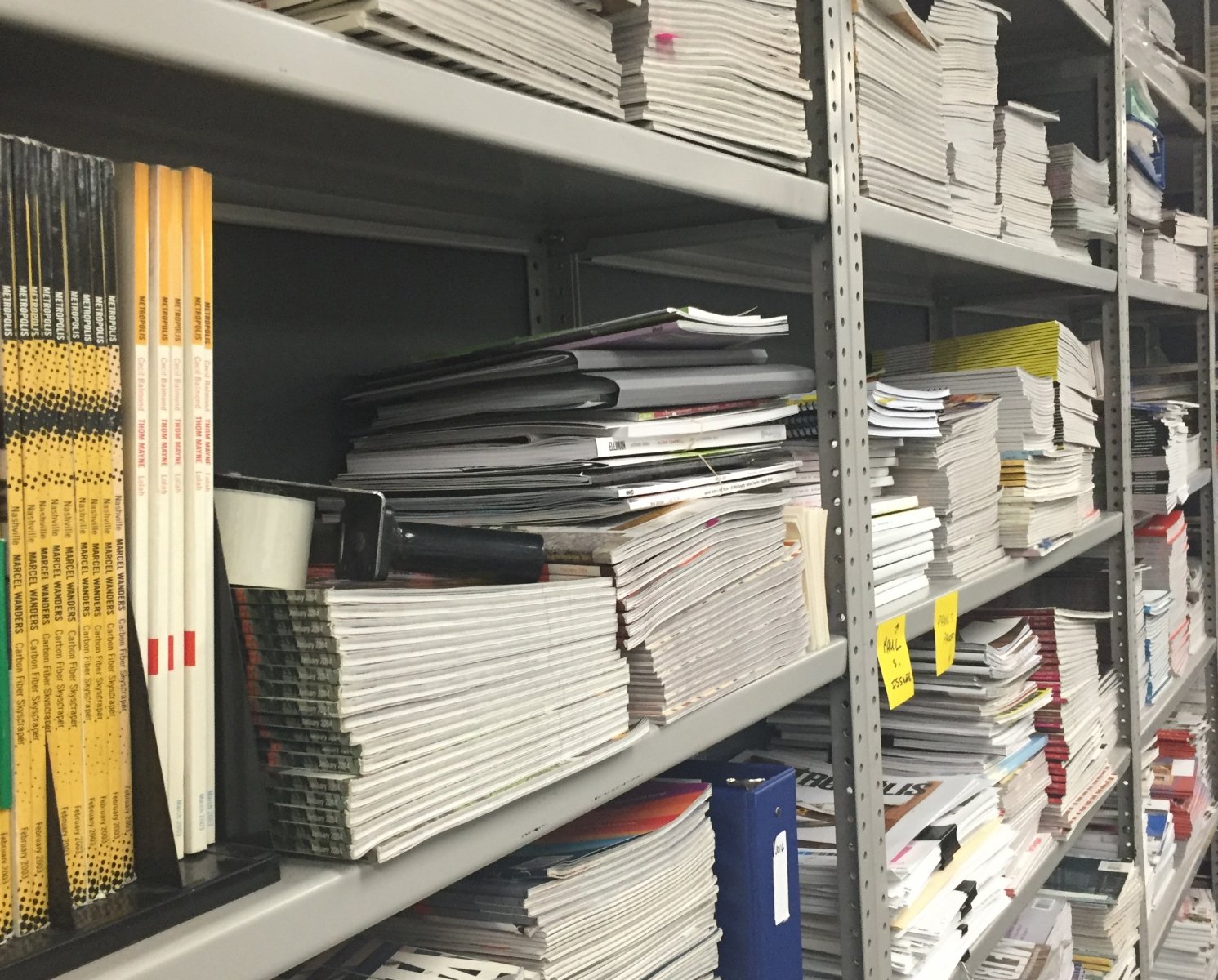

Prior to our move, massive amounts of paper from files, as well as magazines and books, went to be recycled. This industrial process was an efficient one. Large plastic bins on wheels were filled with all manner of papers, including the posters I once fondly taped to my door and wall. A truck parked downstairs ground up the content of a dozen bins in a matter of minutes. All that we once thought important, all that recorded knowledge, is gone—trash.

Before the mania for everything digital took over, I used to think that the paper archives of the magazine would be important to keep for future scholars. Now they have no value. (I admit that much of what I filed away held no interest for anyone, but there were some old speeches, never digitized, and notebooks that I decided to save.) Toward the end of this recycling frenzy, I took armfuls of files and, without looking at their content, threw them into the bin. As I coped with this vivid experience of loss, I heard of a similar purge that portends a greater absence than the tossing of my files.

When I wrote in the October issue about the passing of Olga Gueft, the editor of Interiors who was also a mentor to me and countless others, I was working with a brief obit I found online. Later I heard that her extensive archives were destroyed. The thousands of photographs she took of new buildings, interiors, people, and events—a record of the state of interior design as it evolved through the years, and the people who made that evolution possible; her clippings of news stories through decades of avid reading; notes for her never-written book about the story of a profession she loved. More trash.

All this trash makes me wonder—in our mad dash into the digital world, what happens to our nondigital history? Billions are invested every day in apps, gadgets, and services that will eventually become obsolete as “smart money” finds new ventures. Who will invest in archiving the less exciting but still essential physical record of the work it took to build a solid foundation for our professional practices?

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Navigating the Path to Net Zero