January 26, 2015

Liam Casey Plans to Disrupt Manufacturing—by Producing Less

Can making less help us innovate more? This supply-chain guru, who has worked with giants like Apple, is forging connections between sustainable manufacturing and emerging entrepreneurs.

The buzz over the Internet of Things in the last decade ended up being more about the Internet, and not so much about the things. But now that we’ve remembered we need smart devices to go along with our apps, hardware is making a comeback. Liam Casey is perfectly poised for this change in his new, colorful warehouse-cum-office in San Francisco, armed with an entire floor of engineers and prototyping machines.

From that foggy perch, Ireland-born Casey heads up PCH, which develops, manufactures, packages, and distributes some of our most coveted electronic products—think Apple devices, Dr. Dre’s Beats Electronics, and Neil Young’s Pono player. Known as “Mr. China” for his years of experience in Shenzhen’s manufacturing scene, where he’s been working since the 1990s, the 48-year-old could have just ridden the lucrative wave of Chinese manufacturing and retired to Boca Raton. Instead, he got disruptive.

For someone dedicated to product, Casey wants to make less of it. And for good reason: Making more than what will sell is the opposite of sustainable—financially and environmentally. Electronics are resource intensive and generate significant waste. Producing too much also slows down new ideas. “What kills innovation when it comes to hardware is inventory,” says Casey. “The venture capital world is afraid of a long channel of inventory that may never sell. One of the best ways to be sustainable is to make fewer products.”

Employees box products at a PCH factory in Shenzhen—they understand that the experience of unboxing is important to electronics retailers like Apple. Casey has prioritized the well-being of these employees, implementing a hotline, educational centers, and social events, as well as a zero-tolerance policy to any kind of abuse. These programs are an integral part of PCH’s sustainability initiatives.

So he’s figured out solutions for shrinking the time between when something’s made and when it’s sold—so that it’s practically on demand. “We try to replace inventory with data—live data of what’s been selling,” says Casey, who admits efficiency doesn’t solve all environmental problems. But producing, shipping, storing, reshipping, and holding product locally, before it gets to the consumer, all costs money—and a lot of energy, which is saved with his systems.

Those savings add up, allowing innovative start-ups to jump into the mix. They can bring PCH their prototype, and his Chinese facility will make a small order of, say, 5,000 units, instead of 50,000. If the company has already sold half of those units on a crowdfunding campaign—as is often the case—then it might not even need additional outside capital to bring its product to market.

Casey is able to work with these start-ups and entrepreneurs on smaller orders precisely because of his years of experience in China, where PCH has its own facility and long-standing histories with other manufacturers. Unlike software, which can be released and then fixed in later iterations, hardware has to be done right the first time. PCH’s attention to detail has to be unwavering. If you want to switch projects quickly and efficiently while keeping up the quality, it comes down to people power, Casey says.

PCH’s product innovation hub, Lime Lab, is based in San Francisco, as part of its hardware start-up incubator program, Highway1.

About 2,800 people do meticulous work in PCH’s Chinese factory, having honed their skills on products for companies like Apple, wherein the customer’s unboxing experience is part of the brand’s magical identity. Casey has invested in these people. In August 2012, the company partnered with the Little Bird hotline service to provide employee support, which resulted in more than 10,000 calls and instant messages between workers and management in 2013 alone. “They call, and they complain about anything they want,” says Casey. Worker loyalty has spiked; over half of them have now been with the company for over a year, versus a quarter of that before they instituted changes.

Casey is realistic: “The work can be monotonous for some people, so what you have to do to retain workers is show them there’s a way to get to a stage where they can leave a factory, and we do that through education,” he says. This means that providing libraries that double as education centers, as well as improving morale with good food and date nights (most of the employees come from other parts of China, so social events matter). The company has a zero-tolerance policy (for itself and its partners), which includes child labor, physical punishment, falsification of time cards, and withholding pay, all of which is detailed in its comprehensive inaugural sustainability report.

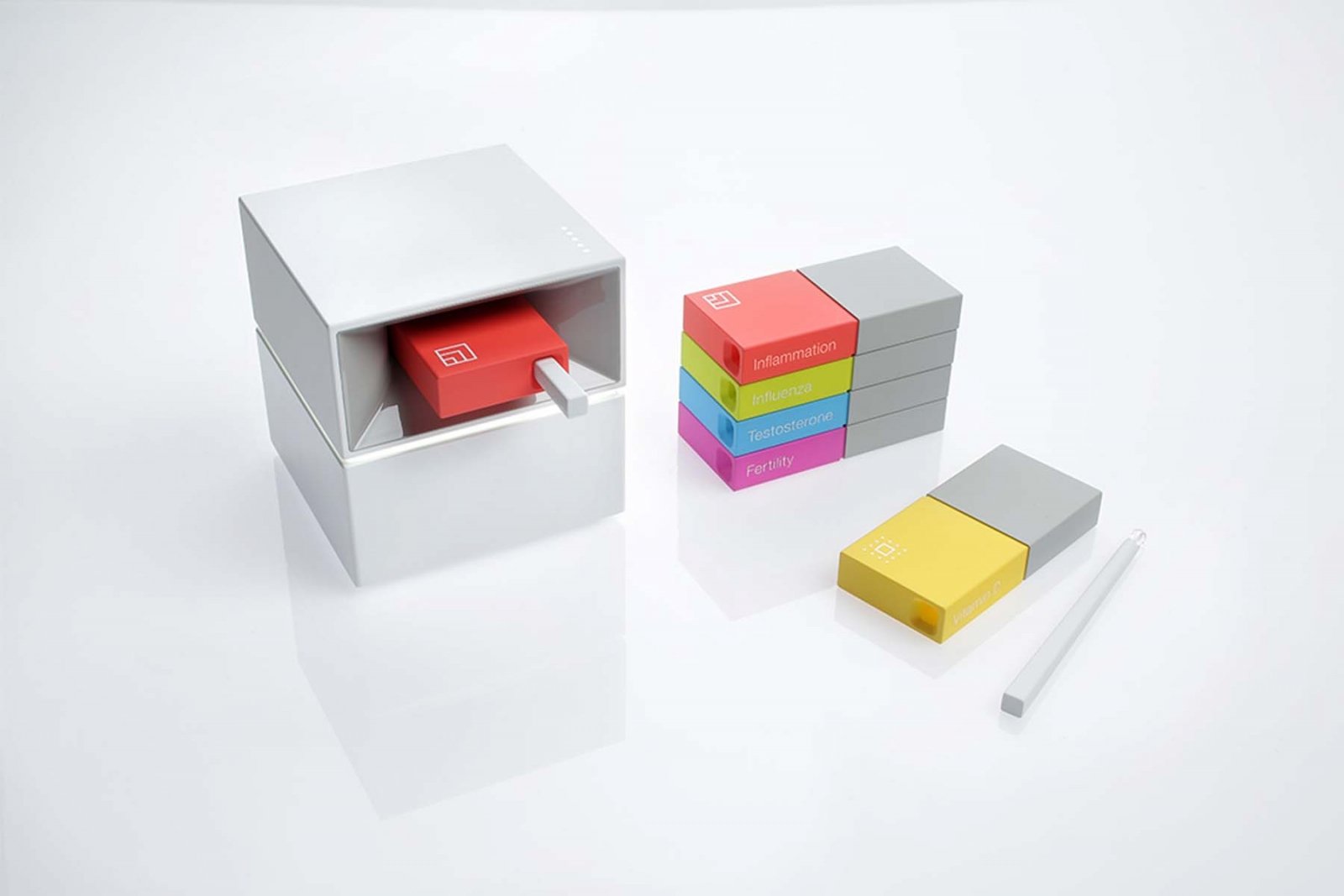

Alumni of this incubator have developed products that include Cue, a deep health tracker that combines powerful biosensor technology with mobile platforms. The product is accepting preorders now.

Casey has worked with some of the best designers in the business. Now, PCH’s start-up incubator, Highway1, is helping bring great ideas from design-minded entrepreneurs to market, assisting them with the logistics leap from prototyping to product-on-the-shelves. “What I love about working with the start-ups is they think about the end product,” says Casey. Products that Highway1’s alumni have developed range from Podo, a stick-and-shoot camera, to Peeple, which notifies you when someone enters or leaves your home. There’s Drop, an iPad-connected kitchen scale; Lagoon, to help homeowners monitor water use; Moxxly, a rethink of the breast pump; and JewlieBots, programmable friendship bracelets to encourage tweens to take up engineering.

Whether whimsical or practical, each has a use that’s clear from its well-thought-out design—and looks great. “If you want to make fewer products, you might as well make beautiful products,” says Casey, seeing the future through the view of late-afternoon San Francisco fog.