August 8, 2012

Q&A: Mayor Mick Cornett

A few years ago few thought of Oklahoma City as a place to visit. Then local citizens decided to invest in themselves. Today the city attracts tourists and jobs. It is also a great place to raise a family. Mick Cornett is now serving his third term as mayor of Oklahoma City. He is the […]

A few years ago few thought of Oklahoma City as a place to visit. Then local citizens decided to invest in themselves. Today the city attracts tourists and jobs. It is also a great place to raise a family. Mick Cornett is now serving his third term as mayor of Oklahoma City. He is the national president of the organization representing Republican Mayors and Local Officials (RMLO) and was named public official of the year by Governing Magazine in 2010. Cornett was the featured guest of First Lady Michelle Obama at the State of Union in large part because he put Oklahoma City “on a diet” in 2007, challenging citizens to lose a collective one-million pounds. The goal was reached in January 2012. More than 47,000 residents logged their weight loss on the awareness campaign’s website.

Jared Green: In The Huffington Post you wrote that twenty-five years ago few companies wanted to come to Oklahoma City because of the lack of amenities. The quality of life wasn’t viewed as great, so you decided to do something about it. What did you understand to be the absolutely necessary pieces in improving quality of life? What was Oklahoma missing?

Mick Cornett: We had established low standards for ourselves. We had considered ourselves a good place to live and a nice place to raise a family, but I don’t think any of us would have maintained that it was a great place to visit. It wasn’t the city where you invited your family and friends from other parts of the country to come visit. We didn’t have a city worth showing off.

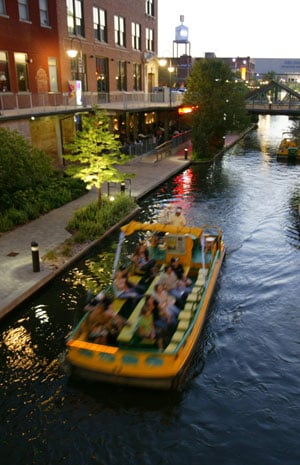

When we started about 20 years ago on this track to create some amenities we were not only proud of but that we create a city worth showing off, a lot of it was just raising the standards for what was acceptable. That included a lot of big projects like building a new ball park and sports arena and putting money into our performing arts center. But there were also water projects and beautification projects along the way — putting a canal through our entertainment district and building dams to actually put a stable body of water into our river. There were a lot of things people who lived in Oklahoma City had just never really considered. We decided to invest in ourselves. Even if no one moved here and created jobs, we’d at least have a better place for us. That was the thinking initially. It’s evolved quite a bit since then.

JG: Since 1993, to finance your MAPS initiatives (Metropolitan Area Projects), which are viewed as a really innovative model for how cities can change themselves with their own money, you used a limited penny tax passed, which you have used to raise more than a billion for local projects. How did the penny tax come about?

MC: The mayor at the time was named Ron Norick. We had been successful in passing some sales tax increases for economic development projects. Now for the most part those projects never came to fruition so the tax was never collected. Nonetheless, he noted that our citizens were willing to invest in themselves for something better. We were trying to kick start a really gloomy economy. The decade of the 1980s was just a horrible time in the state of Oklahoma and a pretty gloomy time in Oklahoma City.

Norick chose the five-year time frame because it was a timeframe people were comfortable with in their own lives. If you bought a new car, chances are you were going to be paying for it for about five years. It seemed like a good, finite opportunity to put something in front of the voters. It would allow them to consider whether or not they thought this was a good way to fund projects. Also, voters took comfort in the fact that it was going to go away, and secondly, that it paid cash. There was no debt in the way we funded these projects. That was fundamentally new, and it’s still new from the way most cities do it.

JG: The first MAPS project took aim at revitalizing Oklahoma City’s downtown. With some $350 million locally-raised funds, the city built a new canal riverfront development zone, ballpark, music hall, and convention center. A huge new park is coming to complement a revamped botanic garden. Why focus on the downtown first? Why was that the priority?

MC: Fundamentally, most people in your city care about two things: They care about their neighborhood and their downtown. A city gets its identity from its core. One of the reasons Oklahoma City succeeded, now looking back 20 years, is that we convinced people who live in the suburbs that the quality of life downtown is important. We’ve convinced them their quality of life is directly related to the intensity of the core, that you can’t be a suburb of nothing.

Myriad Botanical Gardens and Crystal Bridge Tropical Conservatory (project by Office of James Burnett)

Image credit: McNeese Fitzgerald Associates

Myriad Botanical Gardens (project by Office of James Burnett)

Image credit: Carl Shortt

In way too many cities across the country, what you see is some flourishing life in the suburbs and a core that has seen its life disappear. In Oklahoma City what we tried to do was put new life into the core of the city. We want to make a city where at five o’clock people still want to stay, whether they want to live or they want to play, or they want to continue to work. We want downtown to be an inviting place. If your downtown is dead, it’s hard to imagine that life in the suburbs is going to be a whole lot better.

Bricktown canal revitalization

Image credit: City of Oklahoma

JG: A new set of $777 million in investments will create a new downtown park and riverfront recreation opportunities, build out a streetcar system, expand sidewalks and biking trails, and create new senior wellness centers. Another $180 million was raised just to redesign downtown streets. These projects seemed designed to improve the quality of life for locals as much to draw in further private sector investment. But what do you hope to accomplish with the new projects? How are you defining success?

MC: If we’re creating a city that our kids and our grandkids are going to want to choose to live. In the 1980s when my contemporaries and I came of age, there weren’t that many good jobs available. Most people who got an advanced degree had to leave Oklahoma City. We lost a generation of leadership. To a certain extent, some of those people are coming back now.

What we want is to create a city where if a kid grows up in Oklahoma City, they want to remain here if they can. What we’re seeing is not only is that becoming true, but a lot of people are moving here from California, the east coast, and especially Texas. Those are communities that had been a drain on our most promising citizens for generations. Now we’re attracting that human capital. That’s going to be the key to economic development because no longer do people follow jobs. Jobs follow people. We’re succeeding now because we’re attracting the top human capital available.

JG: Are you working with landscape architects on these projects? Also, have any designers really influenced your thinking on how to design successful public spaces? What do you hope to accomplish with these new public spaces?

MC: What we’ve learned is that there wasn’t a lack of enlightenment either at City Hall or in the business community. We had just never prioritized the landscape architecture that can really help beautify a project or a city.

Central Park concept

Image credit: Hargreaves Associates

The city has now got a set of standards. It’s hard to imagine that you’re going to have businesses with high standards in a city that has low standards. When the city developed higher standards — and those are standards that I continually push, given they need to be ever increasing — what you see is that the businesses in the community want to reflect those standards or maybe even exceed them. So it feeds on itself. When you have a city of low standards you’re going to have businesses that exude that same quality. You’re not going to create a city that’s all that impressive or creates interesting opportunities for pedestrians.

We have a number of landscape architects, architects, and designers here in the city who are very capable of doing great work but they had never necessarily been funded or inspired until recently.

I’ve also worked with Jeff Speck, Hon. ASLA, on a series of projects over the last few years. Jeff has helped me learn about many of the ways you can create a more pedestrian-friendly community. We have a long way to go there. Jeff has been a great sounding board for me from the outside-in on what works in certain cities across the country.

But I will say there are wonderful landscape architects right here in Oklahoma City who are now doing incredible work. I can only assume this type of work has been possible for a long, long time. It just hasn’t been standard. Now, it’s the standard and we’re seeing it.

JG: You say that the MAPS projects have yielded $5 billion in private sector investment, much of that in new real estate. With increased residential investment and improved transit and these nice new sidewalks, are you concerned about affordability downtown? How has the population changed since private sector investment has taken off?

MC: There’s great demand downtown. We’ve had so little downtown housing for years. The affordability is an issue, but that’s based on the idea that it almost has to be new construction. Most of the opportunity to live downtown is brand new construction, which costs more. So we are seeing price ranges that are higher than we would like. I’m somewhat concerned about that but I think over time it will start to take care of itself.

There is quite a bit of high-end housing in downtown Oklahoma City. But housing is very affordable in Oklahoma City in general. When people move to the city, they’re very surprised at how affordable our housing stock is whether they want to live in suburbs or downtown.

I can tell you this: There is great demand for downtown housing. What we have yet to resolve is making the housing as affordable as the demand would indicate. When that tipping point arrives, you’re going to see downtown housing explode. Right now, there’s a nice market for it but it’s going to really take off when the price points get closer to the average price for a house.

JG: What are your views on the federal debate on transportation enhancements, federal financing for bicycling and pedestrian infrastructure? The senators from Oklahoma seem to be very opposed to federal support for these measures. Has Oklahoma City ever benefited from transportation enhancement funding?

MC: Well, sure we have and, you know, I’m all for walkability and a more pedestrian-friendly environment. I am for as many of those decisions that can be made locally as possible.

I do have a slightly different take than my senators on this issue but I think both of our senators will tell national audiences how extremely proud they are that Oklahoma City is a perfect example of a city that took care of its own destiny. The fact that we’ve done so much for ourselves might be reflected in their attitudes. Because they’ve seen what can happen. They’ve seen these types of amenities that can be instituted from the ground-up. They approve of that method.

I just like the idea of anything that improves the quality of life in communities, cities tapping into those resources, but I’m not speaking for the funding like they are.

JG: Lastly, you famously put Oklahoma City “on a diet” and recently that initiative hit a benchmark: 1 million pounds lost. Why do you think the campaign took off like it did? How are you connecting your weight loss campaign now to the new park projects, the walking and biking infrastructure?

MC: The new prioritization on obesity here in Oklahoma City was really just a reflection on the idea that we have higher and higher standards. What I noted when I launched the campaign was we were putting higher standards on seemingly everything — except us. We really needed to put higher standards on our health and our children so the campaign was really just an attempt to get a conversation going.

We needed to talk about obesity and health in general. When I came forward and was willing to discuss my own health issues and at the same time was exposing the fact that our city had a large problem with obesity, it allowed people to be more comfortable talking about it inside their home, business, or church. That conversation has been very helpful in getting people to recognize the dangers of obesity and that we need to do something about it.

That conversation was very instrumental in us plugging in some of these healthier concepts into MAPS 3. After that campaign, we were able to say these senior health and wellness centers are going to be important. These jogging and biking trails are instrumental to creating the city that we want our kids to grow up in. We have now made an incredible amount of infrastructure improvements downtown, improving the walkability of our core city.

Sidewalk improvements downtown

Image credit: Office of James Burnett

We are becoming a city where people want to get out and walk, which is really important. For decades, we created a life where everything revolved around the car. That’s less true today. I hope it’s less true in the coming years.

Jared Green is editor of The Dirt, the blog of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). The Dirt covers news on the built and natural environments.

___

This post is syndicated with The Dirt, a weekly news site focused on the built and natural environments with feature stories on landscape architecture; it explores design and policy developments related to land and water use, urbanization, transportation, and climate change.