September 14, 2009

Really Integrated Design

Our writer visits a zero-energy home built into a San Diego hillside.

With forest fires threatening thousands of homes outside Los Angeles last week, and California in its third straight year of drought, alternative models for housing are starting to look better and better.

Professors Don and Ann Cottrell might be able to teach us a thing or two. For thirty years, they’ve lived in the earth-integrated, zero-energy house that they designed and built into a hillside near San Diego State University. Inspired by the nascent environmental movement in the late 1970s, but without many precedents to guide them, they had set out to join the vanguard of the alternative housing movement. Although they hired an architect to advise them on their design and ensure it conformed to building codes, they did much of the actual construction themselves, from the waterproofing to the electrical wiring. “We were just going in blind,” Ann Cottrell told me. “Nobody knew what they were doing back then– it was just so seat of the pants.”

But if any pair of amateurs was well suited to the task, it was the Cottrells. Don is a professor of physics who paid his way through college as an electrician; Ann is a sociologist specializing in the environmental movement. And both of them grew up in very DIY households, where tools were put in their hands at an early age. “We had this role model in our heads, that when you reach a certain age, you build a house,” Ann said.

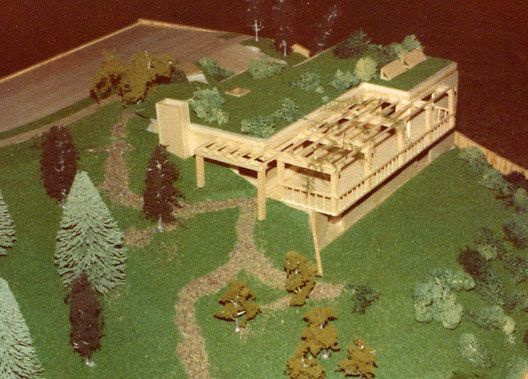

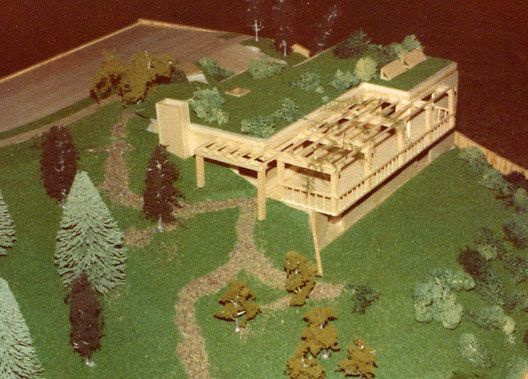

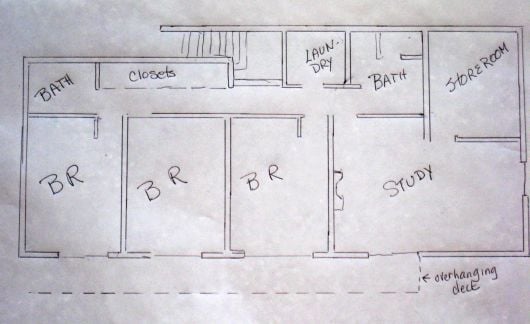

To keep construction simple and cheap, the Cottrells opted for a modular plan. Each of the two floors is made up of five twelve-foot square boxes: on the upper, grade-level floor are the kitchen, dining room, living room and (double-box) garage; on the lower, below-grade floor are three bedrooms and a (double-box) study. Approaching the house from the west, it’s barely distinguishable from the hillside; from the southeast, it’s barely distinguishable from a normal house.

Top: an early model of the Cottrells’ house; bottom, the lower-level floor plan. Photos: courtesy Don and Ann Cottrell

Top: an early model of the Cottrells’ house; bottom, the lower-level floor plan. Photos: courtesy Don and Ann Cottrell

The Cottrells are still on the grid, but solar panels on the roof produce more than enough to compensate for their electricity usage, making the house zero-energy on balance. (In fact, their net electricity consumption is frequently negative, said Ann–but, alas, the power company doesn’t pay them for the excess electricity they generate.) Their water is solar-heated, but they maintain a backup heater in case of long cloudy spells, or guests who prefer to shower in the morning before the sun has had a chance to heat their water.

In the winter the sun stays low in the sky, heating the house as it slants in through the south-facing bank of windows (and aggressively fading the house’s interior in the process, which is why the Cottrells prefer to stick with a white theme for their interior decor). In the summer, the second-floor patio protruding over the bedroom windows keeps them shady and cool. Although summer temperatures in San Diego regularly reach into the triple digits, the house’s interior stays comfortably between 65 and 75 degrees.

The northwest corner of the house, as seen from the street

The northwest corner of the house, as seen from the street

The roof supports an array of solar panels.

The roof supports an array of solar panels.

“San Diego is so perfect for this,” Ann said. “It’s got the moderate climate, and it’s really hilly so you can earth-integrate very easily.” So why, despite the three decades that have passed since the Cottrells first built their home, haven’t more people followed suit? Perhaps the biggest reason, she surmised, is that earth integration isn’t an easily standardized model. With most homes built by developers, a single template produces fifty to a hundred houses at a time, leaving no room for the consideration of individualized topographies that is critical when building into a hillside.

But especially given California’s frequent fires, and the lack of local wood, why isn’t concrete at least more widely-used? In part because it makes retrofitting difficult, Ann admitted. “We thought this house to death when we were planning it,” she said, but they nevertheless discovered that their kitchen didn’t get enough natural light, and so were forced to redo the kitchen years later to install a drop ceiling with lights inside.

Yet another obstacle is the tangle of codes and regulations that were written with more conventional houses in mind, and that often prove irrelevant or counterproductive for an earth-integrated house like the Cottrells’. Even though their house was designed not to need a furnace, building codes insisted on one. Since their green roof is considered “livable space,” it was required to have 10-foot high venting pipes, thwarting their original goal of blending the roof naturally into the hillside. Regulations also mandated that the standard wooden firebreak be installed below the Cottrells’ ceiling–despite the fact that the entire structure is made of inflammable concrete.

The front of the house

The front of the house

Conventional rules also stymied the Cottrells’ plans to refinance their house. Refinancing requires an appraisal, which is typically obtained from the sale prices of similar houses sold that year within a one-mile radius. “We said: But we’re the only earth-integrated house in all of San Diego! You’ve got to be kidding!” recalled Ann.

With no system in place for appraising a house like theirs, the only way to sell it will be for someone to either buy it up front, or obtain an expensive private loan. But at the end of the day, said Ann, “We didn’t build this house to sell it. We built it to live in.”