May 16, 2018

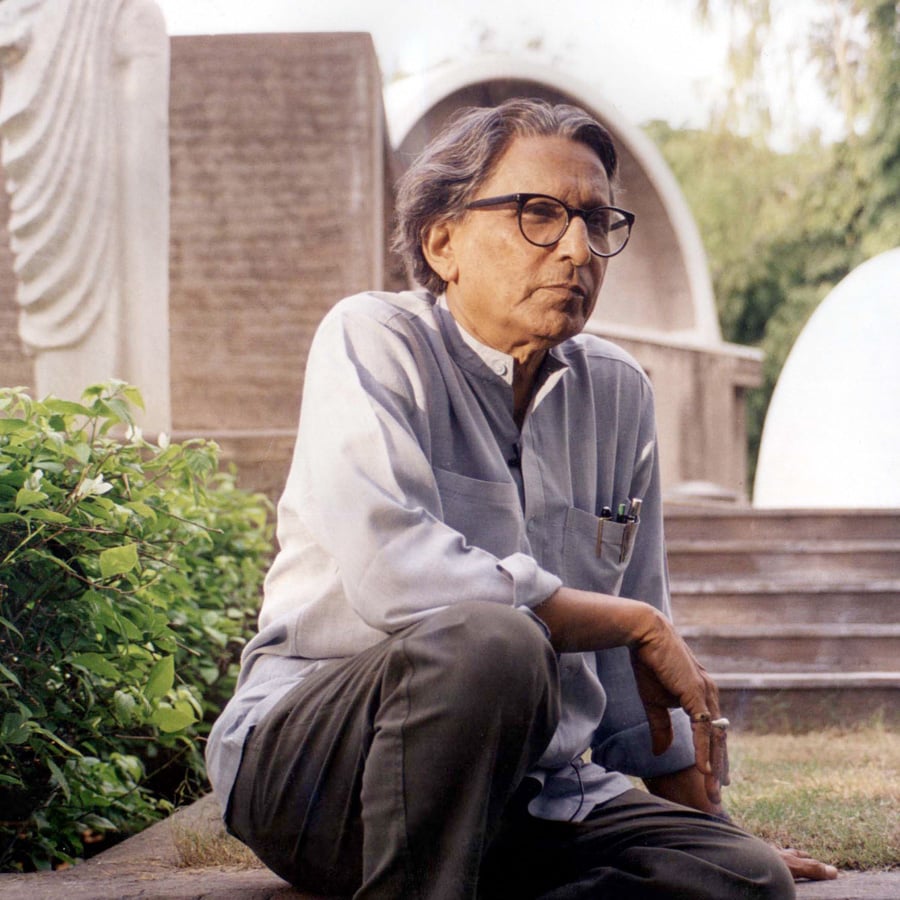

The Enduring Wisdom of Balkrishna Doshi

The Indian architect, who receives his Pritzker Architecture Prize today, exudes a joyful humility, akin to his architecture.

Balkrishna Doshi keeps his idols close. At the entryway to his architecture studio, a palm-shaded oasis set within the bustle of Ahmedabad, India, he displays images of the deities Ganesha, the elephant-headed lord of prosperity, and Durga, a goddess representing the triumph of good over evil. Among them, is a portrait of the great Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier.

This curious triptych forms a felicitous composite of the architect—known simply as “Doshi” to most— and his relationship with his art form, a pursuit he regards as deeply personal and deeply spiritual. But this spirituality doesn’t stem from religiosity, per se: “I think humility is part of spirituality,” Doshi says.

Most architects with a list of accomplishments akin to Doshi’s would have license to have a less humble outlook. Over the course of his career, the 90-year-old architect has built more than 100 buildings, established one of India’s premier design schools, and molded the Modernist principles taught to him by Le Corbusier (“my guru,” he calls him) into an architecture that was distinct, yet distinctly Indian.

Today, Doshi receives the Pritzker Architecture Prize at a ceremony at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, an accolade considered to be the field’s ultimate achievement. He is the first Indian to receive the honor since the prize was established nearly four decades ago.

“Doshi constantly demonstrates that all good architecture and urban planning must not only unite purpose and structure, but must take into account climate, site, technique, and craft,” the Pritzker’s jury wrote in its citation, calling his architecture “serious, never flashy.”

Yet, there is also joy. Recalling his childhood in Pune, India, Doshi explains the values instilled in him by his extended family, his grandfather in particular: “In our tradition we talk about epics and ethics and values. And we celebrate—all the time we celebrate— that the sun rises, and the moon. Space is something very sacred.”

As a child in the 1930s and ’40s, he observed his family, carpenters by trade, at work building furniture—the wood arriving and being transformed into something man-made. He also watched how they lived: “I saw the house gradually grow as [my uncles] added on their own floors. Staircases were added. I could see how those staircases were sandwiched between walls, creating long journeys going up and down.”

An early aptitude for drawing led Doshi to the Sir J.J. College of Architecture in Mumbai in 1947, the year India became a sovereign nation. A friend invited him to move to London while he studied for the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) exam. There, after a fortuitous encounter with Le Corbusier’s assistant, he wrote a letter asking if he might join the architect’s Paris atelier. “I got a reply in French,” he recalls. He rushed to the RIBA library to get the letter translated and learned that Le Corbusier was proposing an eight-month—and unpaid—trainee position. “So, I went,” Doshi says.

The young Indian architect arrived at the studio, unannounced and not speaking a modicum of French. “They were really surprised,” says Doshi. “Corbusier told [his assistant], ‘Since he has come with his bag and coat, take him.’”

Though the hours were long, and he subsisted on a meager diet of bread, olives, and cheese, Doshi found an unlikely mentor in Le Corbusier, who spoke of architecture in the same way his grandfather used to tell epic tales. “He was talking about a pact with nature. He would talk about the sun and the shadow, really describing wonderment in spaces,” Doshi says. “He became my spiritual mentor.”

In 1954, Doshi returned to India to supervise work on Le Corbusier’s buildings for Chandigarh, the newly planned capital for the Indian states Haryana and Punjab, and in Ahmedabad. Two years later, he opened his own architecture practice in the latter city. Doshi’s work was inflected with Modernist geometries, but with the familiar materials and traditions of his country. In the ensuing years, he built several social housing projects such as ATIRA Low Cost Housing (1958), and Aranya Low Cost Housing in Indore (1989), whose winding groupings of dwellings, courtyards, and passages houses more than 80,000 residents, allowing for the same incrementalism that he observed in his childhood home.

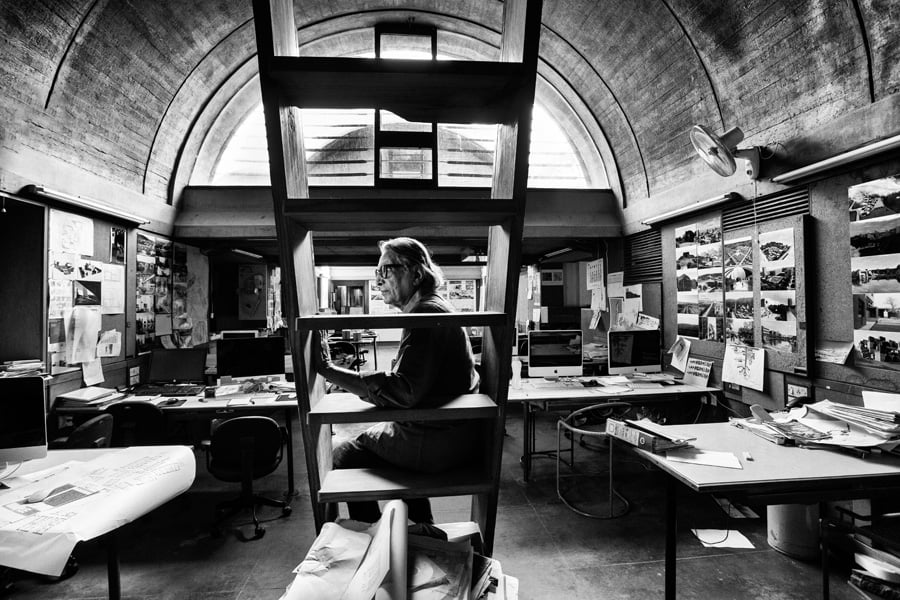

He collaborated with Louis Kahn on the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad (1962), and went on to design dozens of other buildings in that city, including the Institute of Indology (1962) which though distinctly Corbusian, was influenced by the traditional dwellings of Jain monks; the cavernous Amdavad Ni Gufa gallery (1994), which was created in collaboration with India’s foremost Modernist painter; and numerous institutional and residential buildings—including his own architecture studio, a masterful composition of barrel vaults and gardens. Though he came to develop a distinctive design vocabulary, he kept the principles of Le Corbusier and his grandfather at its core: the celebration of sunlight, shade, and breezes. “The energy of space is very important. That energy is what we must feel deep in our hearts. Once we feel that, we are creating architecture,” he says.

Doshi’s greatest accomplishment is arguably his contributions to academia. He established the School of Architecture and Planning (now known as CEPT University) in the early 1960s, after teaching at Washington University in St. Louis, at the bequest of Buckminster Fuller. Describing his alma mater, J.J. College, Doshi recalls, “There was one old building with five rooms and there was a library with only a few cupboards. At Washington U, I saw large spaces, I saw strong tables, I saw big library. I said, ‘You know, we need that kind of atmosphere.’” He envisioned a mixed curriculum, and a international roster of visiting faculty. For Doshi, “Education has to be without doors, and without boundaries.”

Today the university has grown to five departments and is one of the most prestigious schools in India. And Doshi plays the part of the guru to hundreds of students, just as Le Corbusier was to him. Over the phone, he speaks deliberately, each sentence unfolding as a proverb. But he gently refutes comparisons to his famed teacher. “I am their senior colleague, or elder brother,” he says of his students. “Not the guru.”

He is deeply concerned with the state of architectural education today, mainly the increasing disconnect between design and the process of making. “We think it is a production line, not a creative process,” Doshi insists, his voice becoming more adamant. “We are not making models. Neither are we doing historical studies and looking at how buildings were made, and how the space and the light was. How does one know the weight of a brick, or plywood, or a piece glass? I think [students] should feel it.”

Doshi also advocates for a similarly hands-on approach outside of school, mainly in addressing issues within contemporary India, such as preservation (including a decade-long pillaging of items designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret for Chandigarh) and the consequences—both good and bad—of India’s rapid development. “Self-help is very important,” he says of the role of architects locally. “We can’t just sit in an air conditioned room. You need to learn about social relationships, emotional relationships, of living together, of being compassionate, helpful, and tolerant. I think all these things are to be learned by architects, which we have not.”

On the other hand, he says, “if there are no challenges, how can we invent things?”

Doshi, who will celebrate his 91st birthday this August, has no plans of slowing down. He remains exceptionally active, hosting student tours of his studio, delivering lectures, and even making a cameo in a Bollywood film as himself.

“For me, architecture is a journey. It is not a static building,” he says. He views his Pritzker win as a joyous outcome of that journey. “It’s a great discovery to know that there is something unknown, still next door to you or just beside you. And that unknown is the most interesting part of life—a surprise.”

Stream Doshi’s Pritzker Architecture Prize address live today at 6:30pm EST via Facebook and Instagram (@UofTDaniels).

You might also like, “Ole Scheeren on the Music That Inspires Him.”