October 27, 2015

LAB.PRO.FAB Use a Bottom-Up Approach That Puts Good Design in the Service of Communities

The Caracas–based architects champion a bottom-up approach that strengthens community ties and puts good design in the hands of the public.

Nominated by Martino Stierli

Built into the hillside of one of Caracas’s most populated areas, the Programmatic Platform stands out as a symbol of community.

Courtesy Iwan Baan

Living in informal settlements poses many challenges, including limited access to basic services like water and electricity, lack of landownership or land-use regulations, and the need to build shelter efficiently and inexpensively. But because of this, these neighborhoods—home to between a quarter and a third of the world’s urban population—are a laboratory for some of the most innovative, sustainable, and reproducible construction techniques. It is this design spirit that Caracas, Venezuela-based LAB.PRO.FAB promotes in LAB.PRO.FAB—The Public Machinery, a series of community projects for the urban periphery.

Cofounded by architect Alejandro Haiek and artist Eleanna Cadalso, LAB.PRO.FAB seeks to understand the city as a social system, and the built environment as the shaper of that system. “Architecture shapes logistics chains and actions more than it shapes bricks,” says Haiek. “In this sense, what we are trying to do is to create protocols for occupying unused or interstitial landscapes to form new ecosystems rather than just buildings.”

One such landscape—a former parking lot at the center of a densely populated neighborhood ringed by busy highways and a military base—plays host to the studio’s Interstitial Park for the Tiuna el Fuerte Foundation, winner of the first International Award for Public Art in 2013. Composed of bright green shipping containers encircling open space, the park has become a catalyst for many types of social interaction formerly unavailable to residents. Its modules contain a cafeteria, workshops for art and science education, offices, a radio station, auditoriums, and a music-editing studio. The park also allows residents greater political autonomy, as the various NGOs using the space have formed a system of self-governance to help it develop.

All of this would not be possible without LAB.PRO.FAB’s unique approach and design process, which starts by performing extensive research on a particular neighborhood and working closely with its builders and artisans. “We develop a cartography of materials, including where to find resources, where they come from, how they are processed, how to create tools, and how to transform them,” Haiek says.

This initial research is in line with the studio’s design philosophy, tecnicas mestizas/inteligencias locales (mestizo techniques/local intelligence), which posits that bottom-up design is often vastly more effective than any traditional architectural practice involving hierarchical decision making. Haiek also distances the studio from other types of top-down humanitarian practice. “It’s not philanthropy, it’s not altruism,” he says. “We are trying to be part of the community. Architects still understand the communities they work in from the point of view of outsiders, and we are trying to join ourselves to the community as citizens and to preexisting urban resilience.” The best way to do this is to produce what the community is asking for.

This is clearly seen in the Programmatic Platform, a hybrid structure developed as a result of consistent efforts by the community council of the Lomas de Urdaneta neighborhood to build a sports center. LAB.PRO.FAB’s design rests on a steep slope in a location where winding staircases serve as streets, its basketball court projecting over rooftops below. Another project: The Reprogrammed Obsolescence, a multipurpose community center, adopts the never-finished structure of an abandoned mental institution as its foundation, culminating in a multiuse hall covered in an intricate latticed roof.

Although these last two projects were completed with some support from local authorities, the studio prefers to keep its work completely independent. “When the construction companies come to the site, they have their own protocols, their own techniques,” Haiek says. He also adds that projects last longer and are more effective when their future users are in control. “When the people create their own components, if some components fail, they can fix it, improve it, or adapt it with a different material and use.” This semiofficial support also reflects the fragile status of the projects: All of them are technically illegal, or as Haiek terms them, “urban accidents,” because they don’t have any regulation or urban control.

LAB.PRO.FAB, then, is dedicated to a democratic type of architecture—one built from consensus, cooperation, and, above all, the autonomous will of the community. According to Haiek and Cadalso, “Architecture and urbanism are practices that have accompanied power and have rarely developed mechanisms to enable resistance.” Their public machinery is clearing a new way forward.

See the rest of this year’s new talents here.

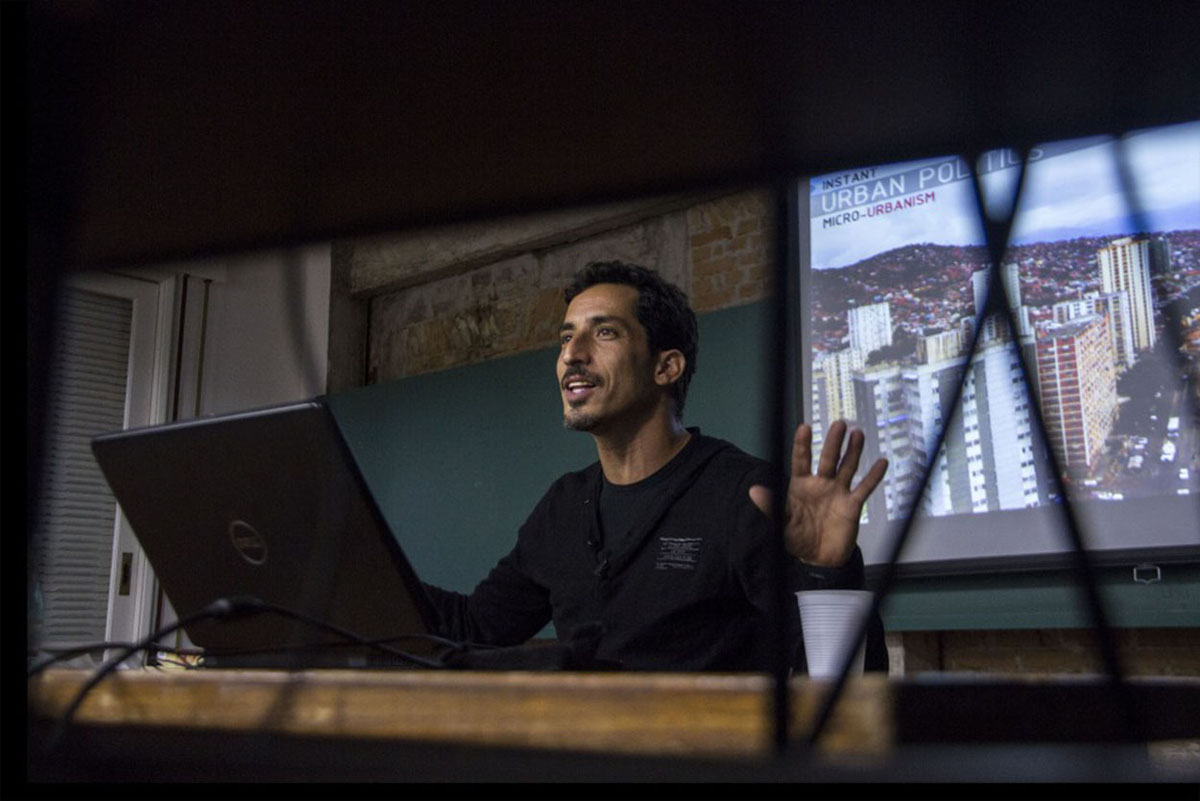

LAB.PRO.FAB co-founder Alejandro Haiek

Courtesy Bruno Buccalo

LAB.PRO.FAB—The Public Machinery’s Interstitial Park for the Tiuna el Fuerte Foundation (more commonly known as the Tiuna el Fuerte Cultural Park) is located in Caracas’s El Valle neighborhood, one of the most artistic communities in the city. More than 500 children and teenagers visit the park each day.

Courtesy Iwan Baan

The Programmatic Platform is a hybrid structure that combines cultural, sporting, and healthcare spaces under one roof.

Courtesy Iwan Baan

The Reprogrammed Obsolescence Multipurpose Community Center Simón Rodríguez illustrates LAB.PRO.FAB—The Public Machinery’s focus on the recovery and reactivation of abandoned infrastructure.

Courtesy Iwan Baan

The foundations of an unfinished building were used to create the new community hall supported by the local participatory council and local government.

Courtesy Iwan Baan

“What deserves particular attention is the design ethic that LAB.PRO.FAB calls tecnicas mestizas/inteligencias locales. They collaborate with the construction-site foreman to form a feedback loop between the different levels of knowledge from designer to builder, thus producing a hybrid approach. In addition, LAB. PRO.FAB also produces evocative designs from simple, prefabricated materials. It sees its contribution in the realm of cultural activism, but its interventions in the texture of the city are transformative both socially and politically, from micro to macro scales.” —Martino Stierli, the Philip Johnson chief curator of architecture and design at MoMA