November 11, 2019

In X-Ray Architecture, the Metaphor Escapes Control

Beatriz Colomina’s new book overlooks the concrete cruelties of the designed environment.

“The bond between architecture and illness is probably my longest preoccupation,” confesses Beatriz Colomina, the preeminent architectural historian, at the start of her new book, X-Ray Architecture (Lars Müller). Self-diagnosing her “feverish” fascination with the topic, she identifies Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor as a germ, which caused Colomina to begin seeing modern architecture anew, “in terms of all pathologies related to it, real or imagined.”

Both forms end up making appearances in X-Ray Architecture, but, as in Illness as Metaphor, it is tuberculosis and the titular imaging technology with which it is associated that serve as the primary vectors for Colomina’s history. According to her account, around the advent of its appellation as “modern,” architecture became increasingly obsessed with the health of bodies. Architects, here drawn almost entirely from the European canon, started to imagine their work as prophylaxis, treatment, and even cure. The book’s most interesting sections document the medical facilities that Alvar Aalto and others managed to get built—primarily tuberculosis sanatoriums, which, Colomina convincingly argues, furnished modern architecture with enduring formal tropes.

Alongside this formalist reading, she explicates an architectural discourse that conceptualized itself in somatic terms. In some cases, as with the work and writing of Frederick Kiesler, thinking of architecture as if a body and for the sake of a body are synonymic. Too often, however, it is the body, rather than architectural form, that is subject to an injurious stretching to fit with the other. Inspecting the “infinite, uterine cave” of Kiesler’s Endless House (1947–1960), for example, one cannot help but imagine how this “nurturing”—and vertiginously sloping—architecture would accommodate a wheelchair. (Colomina does not venture a guess, preferring to tease out Kiesler’s description of the house’s psychotropic effects.) In fact, Colomina’s book is devoid of the evaluative testimony of any ill, injured, disabled, or dying body not belonging to an architect, a striking omission that reproduces and reinforces an ableist logic at the core of architectural thinking both past and present.

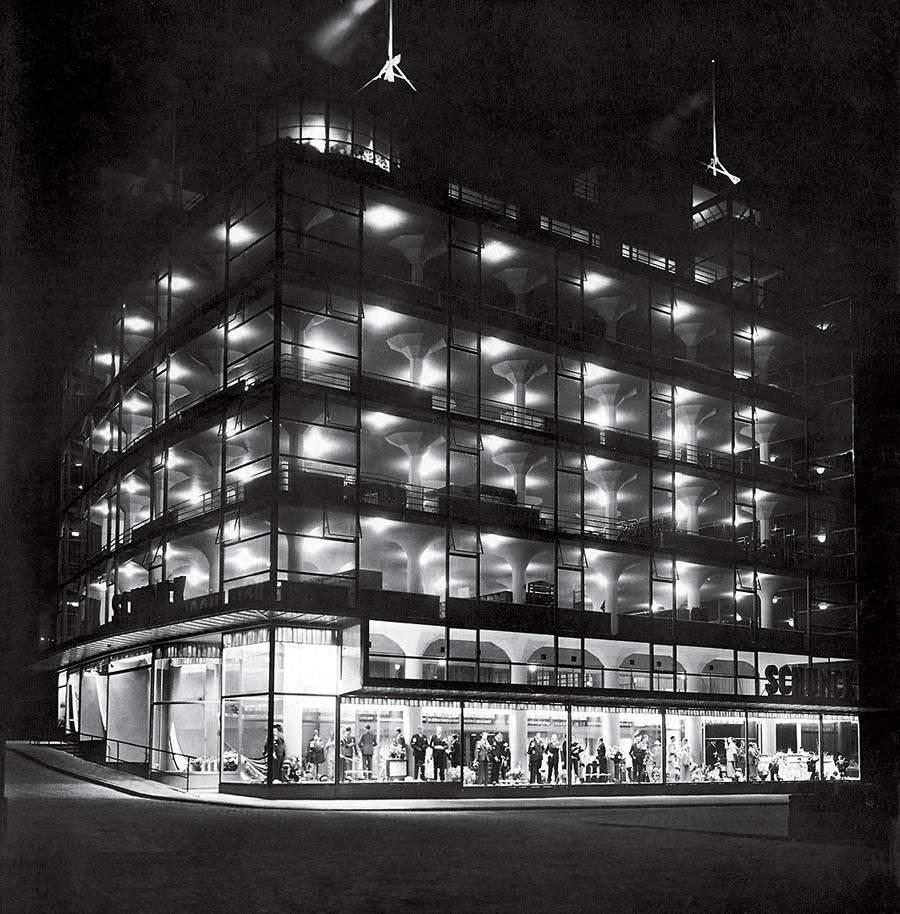

Moving forward in the book’s trajectory, actual bodies—ill or otherwise—are increasingly left behind, as architects such as Mies van der Rohe appropriate the somatechnical landscape of medicine and its visual economy, in particular images produced through radiography, both as source material for formal invention and as self-reflexive metaphor for the discipline. The allure of the figurative takes hold of Colomina, too: “To analyze the canon of modern architecture is to do a kind of X-ray of the canon, a disciplinary self-exposure, a way of getting closer to our object by allowing architecture to see itself, to see what is always there, but overlooked.” Idealized in its linguistic transposition, the X ray itself begins to slip from view.

Privileging radiography as a technique of exposure, X-Ray Architecture pays scant attention to the flesh it has irradiated, the misreadings it has generated, or the money that has been demanded in exchange for it—which, after all, is the technology that determines, much more than X rays or hospitals, who is allowed to live and who is made to die. Instead, the book proceeds from a history of radiographic imagery and its influence on the architectural imaginary to a laudatory essay on the effect of transparent and translucent materials in the work of SANAA, particularly its 2008 installation at Mies’s Barcelona Pavilion. By this point the X-ray metaphor feels tired and worn: Bodies, real or imagined, are abandoned altogether and architecture appears to burrow into a celebration of its own internal discourse and patrimony (“SANAA is the inheritor of Miesian transparency,” Colomina raves.)

In a sense, X-Ray Architecture is several small books bound together as one, and it perhaps would have been better left in parts. Its issues lie less in its individual chapters, most of which are excellent and deeply considered, than in the whole they assemble. Because it culminates in a celebration of an architectural work far removed from the concerns of ill or injured bodies, the book reads as approving of the course it traces, albeit unevenly, from a literal concern for the relationship between architecture and bodies to a strictly figurative one. What matters, it seems to suggest, is what inspires the architect.

Colomina’s title, itself a neologism assembled through metaphor, compounds this problem. Metaphors are built upon metaphors, forming a fragile semantic structure. After all, as Sontag famously explicated, the language of medicine is itself saturated with substitution. Deployed as if a treatment, it frequently acts as a poison. A 2010 study found that two-thirds of doctors surveyed employed metaphors in conversations with seriously ill patients. The researchers claimed that this improves communication between experts and the rest of us, but that simplifies things a bit. Echoing Sontag’s thesis, research on female breast cancer patients conducted in 2003 found that those “who ascribed a negative meaning of illness with choices such as ‘enemy,’ ‘loss,’ or ‘punishment’ had significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety and poorer quality of life than women who indicated a more positive meaning.” The metaphor, in this case, escaped control. In cognitive linguistics, metaphor is often understood as the deployment of a more familiar “source” concept (e.g., radiography) in order to make sense of or enrich the meaning of an abstract “target” concept (e.g., architecture). In their foundational 1980 text Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson assert that the “primary function” of metaphor is understanding. In this, they echo Aristotle, who, many centuries earlier, wrote that metaphor “consists in giving the thing a name that belongs to something else,” and that “to produce a good metaphor is to see a likeness.” But if there can be “good” metaphors, there can also be “bad” ones. Some constitute what a literary theorist would pronounce a “dead metaphor,” or a conceptual image that has been worn away by usage and time, employed automatically and often unthinkingly.

One might venture that “X-ray architecture” is a bad metaphor, although perhaps not a dead one. The source concept is familiar, indeed, as are its visual properties: translucency, skeletal structures, backlit forms, etc. An image comes to mind. Yet the X ray here also refers to actual radiographs and the medical facilities designed concurrently with them. Already a shadow of something else, the radiograph is asked to stand in for two modes of architectural thinking that, while perhaps similar on the surface, are in fact quite distinct. On the one hand there are the buildings that look like X rays; on the other, the buildings designed for bodies that require them. Rather than clarify, the metaphor confuses. What matters? Bodies or architecture? In fact, the question misleads. For medicine and medicalized bodies to serve as metaphors for architecture, they must first be distinguished from it. That is, in order for a metaphor to suggest a similarity, it requires and asserts a more foundational difference. A thing cannot resemble itself, only something other. Proximity is another name for distance.

“Design always presents itself as serving the human but its real ambition is to redesign the human,” writes Colomina alongside Mark Wigley elsewhere. The thesis holds, but the emphasis on ambition might prove a misdirection, reifying a correlation between intent and consequence at the expense of absence and accident.

After all, nearly three decades ago, the Institute of Medicine redefined disability as the “gap between a person’s capacities and the demands of relevant, socially defined roles and tasks in a particular physical and social environment.” As such, disability should be understood less as an attribute inherent in the body and more as a product of its relationship to an environment, social and physical, that was constructed for and by others—quite a few of whom were architects. Disability emerges from, or is cultivated by, a failure in architectural thinking. Emboldened by hubristic claims of expertise, architects violently reduce particulars—individual bodies—to normative universals. Irreducibly different human bodies are transmuted into the upright Modulor Man. Rather than perform a roll call of the same self-aggrandizing architects, X-Ray Architecture would have benefited from a closer examination of the relationship between ill, injured, or disabled bodies and a built environment that excludes them. For example, a study of the deferral of ADA requirements to an afterthought—virtually treated in design offices as an impediment to innovative form-making—might have shed greater light on the impact of architecture on the lived experiences of disabled bodies.

Put another way, ableism in architecture is neither accidental nor incidental but rather foundational. Architectural thought perceives a generic body inhabiting the environment but not the environment inhabiting an actual body. It is, effectively, the condition of possibility for architectural thinking as we know it, and it suffuses even books like X-Ray Architecture, written by a scholar who has likely done more than any other to deconstruct the walls of the discipline’s self-enclosure. After all, the architectural discipline as such can exist within its imagined autonomy only by refusing to understand the design of the environment as, first and foremost, the design of the bodies of others—not metaphorically and not generally, but concretely and individually. The normative proxy bodies that litter the history of architecture both embody and enable this refusal, and disability is necessarily its by-product. Architecture, canonized in this way, can only ever be a dead metaphor: Rather than express a relationship among real people and real things, it appears a self-contained object with intrinsic value—and what gets lost far exceeds semantics.

You may also enjoy “Exhibitions on Both Sides of the Atlantic Ponder Future Life—on Earth, and Beyond.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]