February 14, 2014

Faust on West 53rd Street: The Demise of the American Folk Art Museum

The fate of the former American Folk Art Museum has our columnist thinking about Marshall Berman and Goethe.

The Museum of Modern Art, in New York, plans to raze the former American Folk Art Museum (AFAM) later this year to make way for a luxury high-rise apartment building and museum expansion.

Photos courtesy Giles Ashford

After philosopher and scholar Marshall Berman died in September, I reread portions of All That is Solid Melts into Air, his riveting 1982 polemic on “the experience of modernity.” In one of the most memorable sections, Berman casts Goethe’s Faust as a developer, setting the stage for a later chapter about Robert Moses and the Cross Bronx Expressway. As Berman tells it, Faust—in close collaboration with Mephisto—embarks on a monumental Tennessee Valley Authority–style reclamation scheme, creating harbors and canals along a previously untamed seaside. “The whole region around him has been renewed, and a whole new society created in his image,” Berman wrote. “Only one small piece of ground along the coast remains as it was before. This is occupied by Philemon and Baucis, a sweet old couple who have been there from time out of mind. They have a little cottage on the dunes, a chapel with a little bell, a garden full of linden trees….”

As Berman saw it, this elderly couple “is the first embodiment in literature of a category of people that is going to be very large in modern history: people who are in the way—in the way of history, of progress, of development—people who are classified, and disposed of, as obsolete.” This is roughly the story of the building designed and erected to house the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM). Granted, it’s no cottage, but at townhouse scale—eight stories tall with a 40-by-100 footprint—it’s about as diminutive as a midtown Manhattan building can be.

Designed by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects (TWBTA), the new AFAM opened its doors just three months after 9/11 and was hailed as a symbol of renewal. When the quirky 40,000-square-foot museum with the sculpted bronze facade went bankrupt in 2011, the building was purchased by its neighbor: the 630,000-square-foot Museum of Modern Art. Last April, MoMA announced its intention to demolish the AFAM as part of a long-delayed expansion into the base of a Jean Nouvel–designed tower just west of the existing museum. After a public outcry, MoMA backpedaled slightly, and hired the firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro to study what MoMA had begun to refer to as its “campus.” When, eight months later, MoMA reasserted its intention to tear down the little museum, the response, once again, was outrage. “Tod Williams and Billie Tsien’s twelve-year-old gem has to go,” wrote New York magazine’s Justin Davidson. “Because, like a cobbler’s shack next to an airport, it’s in the way.”

And so, on a frigid January night, a panel discussed the matter with the public at the New York Society for Ethical Culture (NYSEC) auditorium. MoMA director Glenn D. Lowry and architect Elizabeth Diller made their case to a packed house, mostly architects (Williams and Tsien were not there). Diller’s presentation was detailed and extensive, involving a lot of floor plans, sections, and diagrams, all designed to demonstrate how—in order to create a workable circulation path from the existing MoMA galleries to some 39,000 square feet of new gallery space in the base of the Nouvel tower—the multitudes of art lovers would have to be funneled through the space currently occupied by the AFAM. Diller explained her team’s heroic efforts to somehow make this relentless surge of museum visitors compatible with the smaller building, known for its intimate galleries, winding staircase, and floor plates that do not meet MoMA’s. In the end, Diller said, she realized that the demands of MoMA—its curatorial approach, structure, and crowds—would require destroying most of what made the AFAM so distinctive. Better to tear it all down.

Interior of the AFAM, illustrating the building’s particularly quirky sectional changes, which would disrupt the continuous floorplates of MoMA’s expansion.

Unmentioned and unexamined was a different approach: just leaving the AFAM be. Eliminate it from MoMA’s circulation pattern altogether. Let it continue to exist as a freestanding structure, as some sort of satellite space, akin to MoMA’s PS1 in Queens. At the January gathering, the only person who alluded to this possibility was a member of a panel moderated by Cranbrook Academy of Art director, Reed Kroloff. Karen Stein, the former Phaidon Press editorial director, pointed out something glaring that had gone unmentioned in the whole debate over the AFAM’s fate.

In 2007, when MoMA made its Nouvel-designed tower public, there was a circulation plan and it couldn’t possibly have involved the footprint of AFAM because the smaller museum was still a going concern. Back then, Stein pointed out, MoMA “accepted a scheme that didn’t have a continuous loop circulation.”

Kroloff didn’t solicit a response to Stein’s remark from any of the panel members, nor Lowry and Diller. So the next day I contacted another member of the panel—Stephen Rustow, principal of Museoplan, an architecture firm specializing in museums and galleries. In 2007, working as a consultant, he’d hammered out MoMA’s gallery requirements for the planned expansion. He told me there was a loop-shaped circulation plan that worked reasonably well within the limits of the Nouvel tower. “It looked like the diagram that Liz showed last night,” said Rustow, “except that, instead of squeezing the red circulation line as tight as she showed it, it was a wider, more normative loop.” In other words, the space occupied by the AFAM was not an essential part of MoMA’s scheme until the bigger museum took ownership of the building.

The other strange thing is that the more Diller lamented the “bespoke” design—quirky and endlessly detailed—that makes the AFAM so incompatible with MoMA’s smooth expanses of white, the more she sounded like she was making an argument for preservation. “It’s a damn shame that the building is so obdurate,” Diller said. Indeed, the AFAM’s unwieldy, one-of-a-kind nature is precisely the reason that it would make a valuable addition to MoMA’s architecture collection. (This week, the MoMA announced that it would preserve the AFAM’s facade.)

The architectural language of Williams and Tsien is famously peculiar. Theirs is not the International Style that MoMA made famous. It’s more of an off-brand, like Czech Cubism. There’s a conspicuous craftsmanship in TWBTA’s work; tactile is the word that’s most often used. You want to experience its buildings with your hands as well as your eyes. For instance, if you visit TWBTA’s newly opened Lakeside Center—a skating complex in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park—you’ll find a compendium of textures: rough stone, smooth tile, a blue ceiling marked with the swoopy trails of symbolic ice skates.

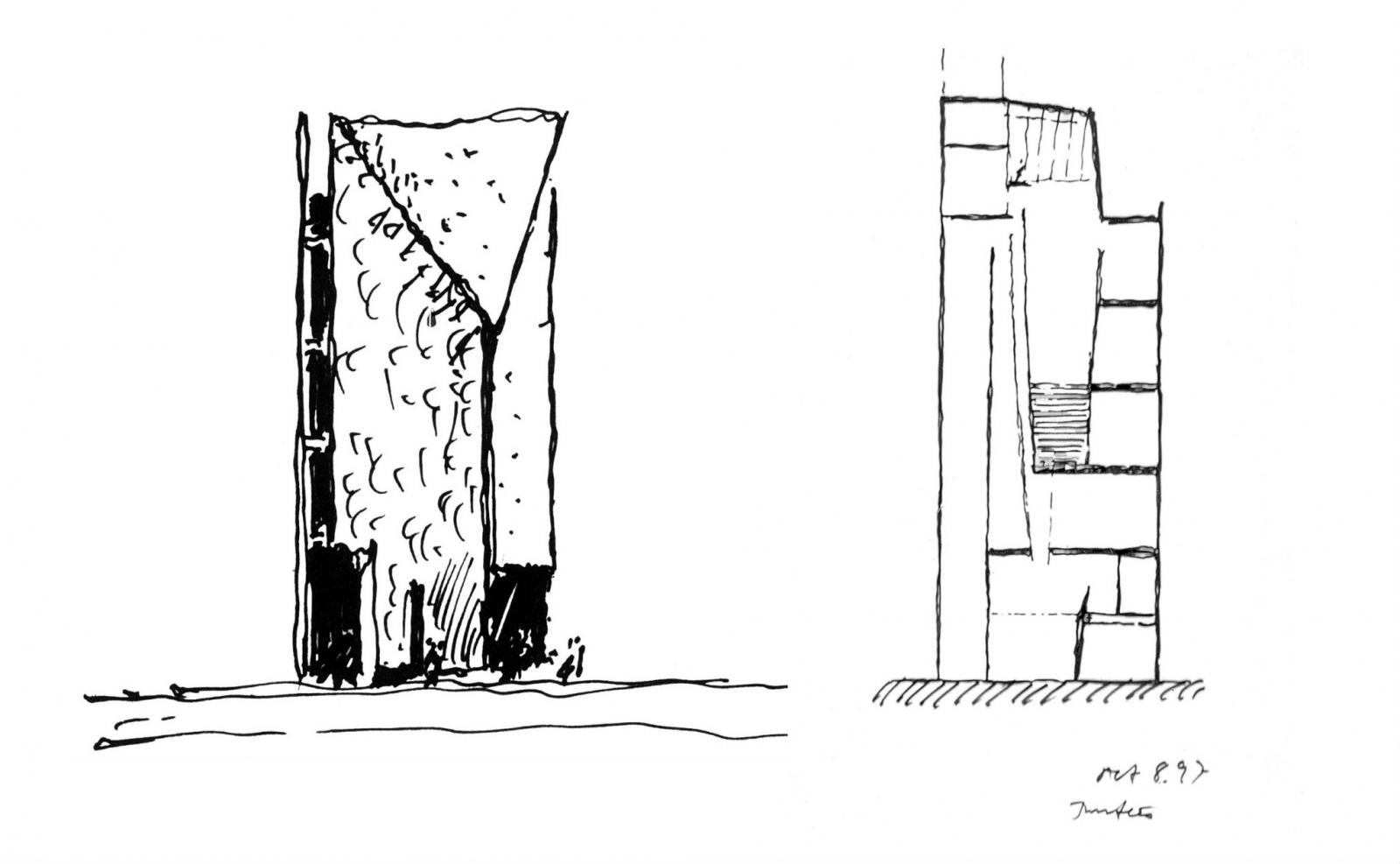

Drawings by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects (TWBTA), designers of AFAM.

Courtesy TWBTA

One day last spring, I had a conversation with Williams and Tsien at their studio on Central Park South. They had just won the Architecture Firm Award from the American Institute of Architects and we were talking about some of their favorite projects, including the AFAM. “You look at the facade and you feel that it was made by human beings,” Tsien told me. “Not rolled out on some assembly line.”

“I should tell you that this was also a labor of love for the people who were building it,” Williams added. So much so that the construction workers went on a field trip with the architects to the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Triennial so they would have a deeper understanding of the design ideas involved. The message the architects wanted to impart to the workers, according to Williams, was: “This is not just any piece of work. We want you to give your best, because it’s something you’ll leave behind.”

“Buildings have memory,” Williams declared. “Places have a memory.”

Glenn D. Lowry’s pitch to the audience at the NYSEC was that MoMA’s continued expansion was all about the art. The collection keeps growing and a new generation of curators needs room to maneuver. It’s an appealing argument, but it’s somewhat undercut by the facts. The planned expansion will add about 40,000 square feet of exhibition space to the museum. While not insubstantial, it’s modest compared to the 750,000 square feet of the Nouvel tower. If you’re going by the numbers, the expansion is about real estate.

As Berman tells it, Goethe’s Faust, infuriated that Philemon and Baucis stand in the way of his total domination of the landscape, offers them money or a new piece of land. But they refuse to move, so Faust orders Mephisto “to get the old people out of the way.” Mephisto has the house burned to the ground and the couple killed. Lowry—despite Michael Wolff’s assertion in The Guardian that he is a “singular enemy of the good”—has done nothing of the kind. But it struck me as odd that no one at that January forum raised the issue of the Nouvel tower, so very controversial only a year or two ago. Yes, the former New York City planning commissioner insisted that 200 feet be lopped off the top so it will now rise only to 1,050 feet, but that’s more than twice the height of its nearest office tower neighbors. There is something decidedly Mephistophelian about the way Lowry obscured the controversy over the excessively tall Nouvel tower behind the shadow of the tiny former museum.