October 30, 2013

Los Angeles Has Never Cared for Landmarks. Except Disney Concert Hall

Ten years later has Gehry’s homage to Uncle Walt’s memory made a difference for LA?

Courtesy of shutterstock.com

On October 23rd, the Walt Disney concert hall, the project that almost never was, celebrated its ten-year anniversary. Throughout these ten years it has had all manner of transformative power attributed to it. But has it really transformed LA? What would the city have been like if it had never been built? Would it be fundamentally different?

The answer? No. The city wouldn’t even be that different in the immediate vicinity of Grand Avenue.

LA does, in fact, have a downtown and in the past ten years it has seen somewhat of a building renaissance and an uptick in gleeful boosterism. But this can’t be attributed to Frank Gehry’s building, no matter how glaringly brilliant it is. After all, the real catalyst for change there was Arata Isozaki’s Museum of Contemporary Art. That’s what got people coming. Even so, for being in the middle of downtown, it’s a relatively sleepy area – like a suburban bedroom community, but with taller buildings.

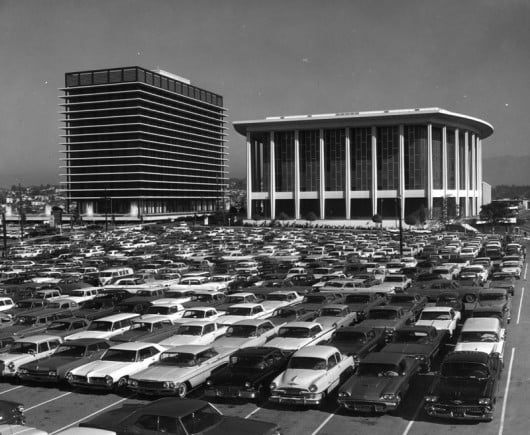

This is not to say, however, that the concert hall hasn’t done anything for downtown. Like the Museum of Contemporary Art, it has played an important role in drawing the imagination (and cars) of the populace “down” to where they normally wouldn’t think of going. Before the museum it was the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion that was the draw.

The future site of the Walt Disney Concert Hall, c.1967.

Courtesy waterandpower.org

If you are from Los Angeles you might even wonder why the concert hall is located where it is. Gehry himself has said that if it had been his decision, he would have sited the Disney on busy Wilshire Boulevard, along Museum Row. He would have put the Museum of Contemporary Art there, too. His logic is based on the notion that Los Angeles, being a linear city that rushes down its boulevards, avenues, and freeways, doesn’t need a downtown. He would have put it where most of the people are and where it’s easy to drive to and park.

Grand Avenue has never functioned like a major thoroughfare. For much of its reach it is one way, running away from the center. If you drive in LA you don’t turn down Grand because it dumps you into this one-way chasm through the congested streets of offices, fast food, and bars. The 110 Freeway dominates just west, flowing around. Grand is often so quiet that is appears forgotten, or perhaps less forgotten than feared (congestion, one-way, expensive parking).

Ostensibly, the Disney is there because it fits into a larger urban scenario whereby Grand is the supposed anchor for the revival of downtown. But this is a relatively old vision for how to revitalize downtown. In reality, the revival is happening elsewhere, on other streets, in other districts, where no landmarks are present. In Los Angeles the landmarks seem to follow rather than catalyze. And though it has many, Los Angeles has never cared for landmarks. It has always loved houses more.

Disney parking structure construction

Courtesy Obayashi USA

So why is the concert hall really there? Three years before it opened, Verso published Mike Davis’ polemical rant, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. In it he states how the concert hall fits into the larger picture of property speculation and downtown development.

As Davis notes, the boards of elite cultural institutions are littered with philanthropic developers and investors like Eli Broad. They are big players in local political campaigns where each successive wave of office holder, whether for mayor or city council, offers big visions for downtown development. Like MOCA before it, the concert hall has been good for property values along Grand. This explains why the few smallish, low-rise cultural institutions on the Grand Avenue axis (MOCA, Disney, the Dorthy Chandler, and currently under construction, Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Broad Museum) are surrounded by super tall corporate high-rises. “Culture fertilizes real estate.”

Davis further describes how “L.A. 2000: A City for the Future” (1988) became “the manifesto of a ‘new regionalism’” that hoped to bring mega-developers and the haute intelligentsia together in order to maintain the momentum of development triggered by the 1984 Olympics. Just four years later, in 1992, construction on Disney hall would commence. 1992 would also see the Los Angeles riots, a reminder that not all was well in the city of the future.

Will Gehry’s new mega-design at last remake Grand Avenue? This model shows an older idea of his for the Avenue.

Courtesy Gehry Partners

Even so, Gehry’s original “blooming flower,” the prototype for the building that would instigate the so-called “Bilbao effect,” could not produce such an effect in the spread-out polyglot city of Los Angeles. Why? It’s because the Disney does little to enliven the street. It does, somewhat, but not enough. As for the energy of the office towers? It rarely spills out onto the street unless it is for lunch or to go home (a home well outside of downtown). Despite the materialization of LA’s future in the form of the concert hall, Grand Avenue remains an archipelago of solitude and, as Davis describes, a “Potemkin Village” of real estate speculation.

So, ten years in, what is the concert hall to the city? Perhaps that is the crux of the issue. It doesn’t have anything to do with the city, per se. It needn’t be anything more than what it is: a magnificent place to listen to magnificent music—and go to the gift shop.

But, despite this, calls for a vision for Grand Avenue continue to consider the Disney as key. Once again Gehry is part of the plan. He is currently involved in a major development being proposed by mega-developer Related, with philanthropist Eli Broad kicking in funds to support the design efforts. An earlier design, conceived by Gensler and Robert AM Stern, failed to wow city officials and stalled out.

Broad said, “I’m convinced with what Frank and Related and others are going to do on Grand Avenue, this is going to be a great tourist attraction and it’s going to bring a great economic benefit to our city.” What history tells us about Grand Avenue, however, is that it is of great economic benefit for a few select individuals rather than the city as a whole. Maybe this time it will be different and the massive scale of this new project will create the critical mass necessary to make Grand a real place. Or it could just end up being another mall.

Perhaps visionaries and investors should cease projecting the ability to transform the city onto singular iconic buildings. But, of course, this would run counter to the logic of culture anchoring development. Will Grand Avenue finally turn around? Most likely not until they make it a two-way, add more trees, bike lanes, and pedestrian amenities. Buildings alone can’t do it, no matter how daring, novel (or expensive) the architecture.

So when it comes to the Disney, and its role in our city, maybe it’s really been here these past ten years to teach us one thing: LA ain’t Bilbao. Fine by me.

For more on the long history of flawed efforts to remake Grand Avenue read the book, Grand Illusion, based on a research studio conducted at the USC School of Architecture.

A version of this article, by Guy Horton, originally appeared on ArchDaily as “The Indicator: Ten Years Later, Has the Disney Concert Hall Made a Difference?”

Guy Horton is a writer based in Los Angeles. In addition to authoring “The Indicator,” he is a frequent contributor to The Architect’s Newspaper, Metropolis Magazine, The Atlantic Cities, and The Huffington Post. He has also written for Architectural Record, GOOD Magazine, and Architect Magazine. You can hear Guy on the radio and podcast as guest host for the show DnA: Design & Architecture on 89.9 FM KCRW out of Los Angeles. Follow Guy on Twitter @GuyHorton.