November 13, 2019

Henry van de Velde: Designing Modernism Offers a Snapshot of Modern Architecture’s Beginnings

Though still largely unknown, the Belgian-born architect and artist forged ideas and places—including the Bauhaus’s predecessor—that defined 20th-century design.

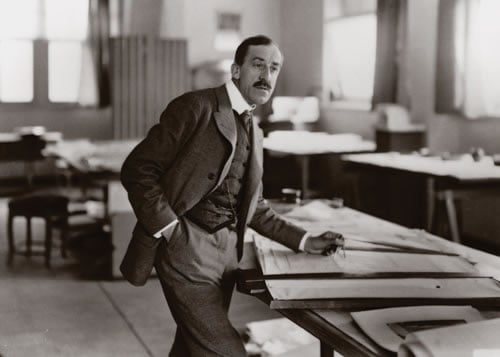

Henry van de Velde is still not well known by the general public, though great figures of modern architecture openly paid tribute to the Belgian artist and Bauhaus pioneer. Hans Scharoun, Erich Mendelsohn, and Alvar Aalto all praised van de Velde as a founder of Modernism.

More than 60 years after the artist’s death, Katherine Kuenzli, professor of art history at Wesleyan University, has published the first monograph on van de Velde in English, subtitled Designing Modernism (Yale University Press, 2019).

Henry van de Velde was born in Antwerp in 1863 and died near Zürich at the age of 94; he worked almost to the end of his days. Trained at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp, he began his career as a painter before turning to the decorative arts and architecture in his 30s. He also published numerous theoretical writings on art, but—above all—was the founder and director of two revolutionary art schools in Europe—one in Germany and one in Belgium—whose aesthetic and pedagogical influences are still extant today.

Numerous books cover van de Velde’s astonishingly diverse career, though they are written predominantly in German, French, and Dutch, and focus on specific aspects of his work or life. Kuenzli chose to cover the entire spectrum of van de Velde’s activities, analyzing them in their philosophical, political, and socio-cultural contexts.

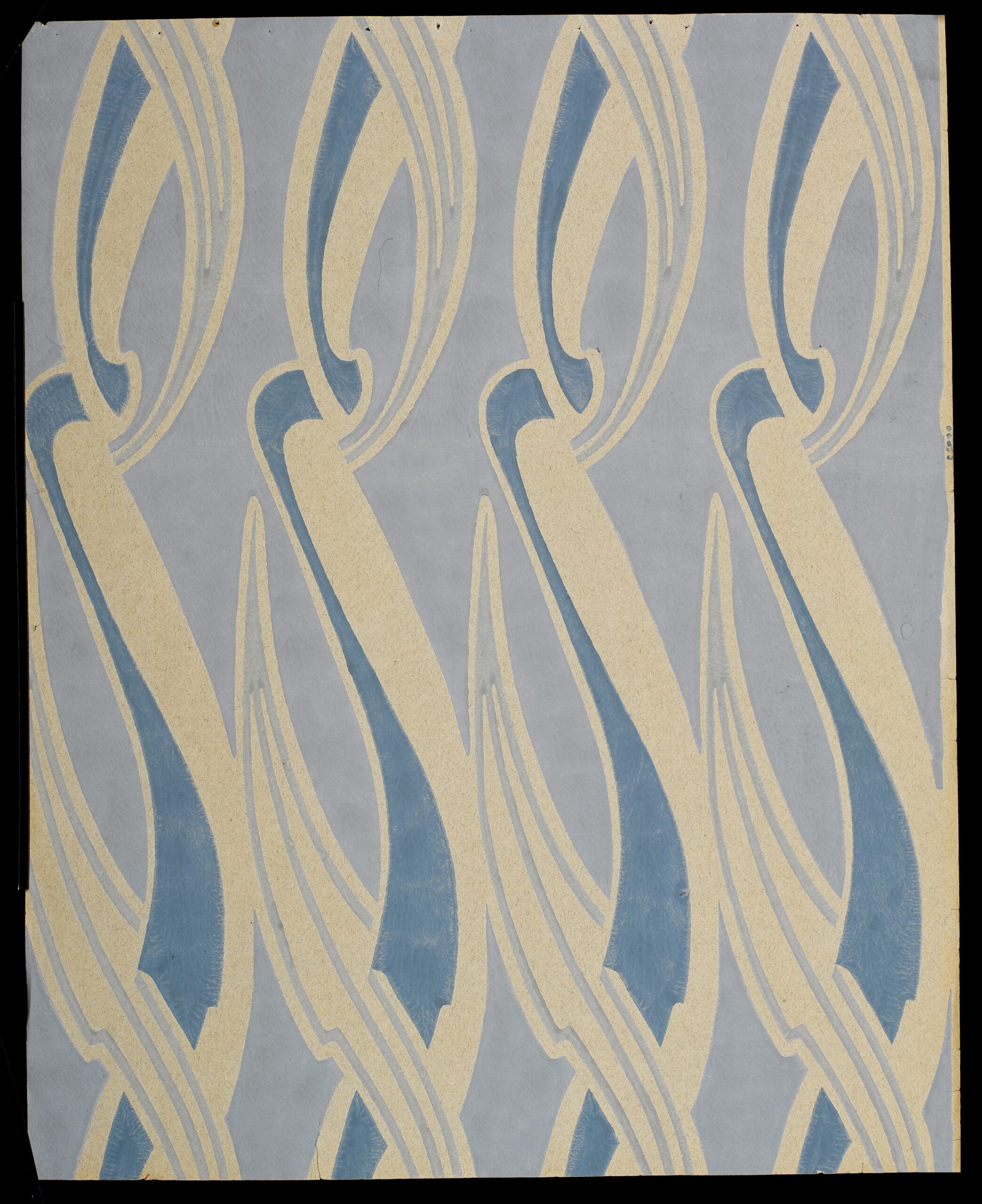

Designing Modernism’s first chapter covers van de Velde’s early experiments in the decorative arts, connecting his painting work to early interiors he designed in Paris and Brussels. Kuenzli demonstrates how his aesthetic practice and theory were shaped by his experiences as neoimpressionist painter.

Van de Velde’s prolific architectural career in early-20th-century Germany dominates the middle chapters of the book. Kuenzli dedicates a chapter each to analyzing the interior for the Museum Folkwang in Hagen (1900), the Grand Ducal School for Applied Arts in Weimar (1907), his contribution to the Applied Arts Exhibition in Dresden (1906), and the theater for the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne. Also emphasized is van de Velde’s role in the Deutscher Werkbund, the union of artists and industrialists whose contribution to German design in the early 20th century.

The final chapter provides an overview of the artist’s life and work in the Netherlands and in Belgium between 1920 and 1947 (van de Velde had to leave Germany for Switzerland during World War I). Somewhat surprisingly, the only architectural achievements considered for this extremely productive period are the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the Netherlands; the Heinemann Hospice in Hannover; and the Central Library and Art History and Archaeology Institute at Ghent University. A section is dedicated to the Institut Supérieur des Arts Décoratifs (ISAD, today ENSAV-La Cambre), which was created in 1926 for van de Velde by Camille Huysmans, the Belgian minister of culture. With the ISAD, van de Velde advanced the revolutionary educational ideas that he had launched with the Weimar School for Applied Arts. (Walter Gropius turned the latter into the Bauhaus in 1919.) Kuenzli also offers a brief overview of van de Velde’s contribution to the reconstruction of Belgium during the German occupation in World War II.

The book concludes with the author’s analysis of van de Velde’s Modernist legacy, evidenced particularly in museums, pedagogies, and functionalisms. “Van de Velde’s contribution to the shaping of Modernism in the first half of the twentieth century is undeniable,” Kuenzli writes, “as is its relevance to today’s world.”

Priska Schmückle von Minckwitz is a Brussels-born, Paris-based freelance writer and preservation consultant who is currently pursuing a PhD in art history, focusing on Henry van de Velde’s theory of ornament. She has been involved in several advisory boards and societies focusing on van de Velde, and worked on the restorations of his Villa Esche in Chemnitz, Germany, and Bloemenwerf in Brussels.

You may also enjoy “In X-Ray Architecture, the Metaphor Escapes Control.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]