October 23, 2018

Hip-Hop Architecture’s Philip Johnson Moment

A new show at AIA New York’s Center for Architecture makes the case for a growing global design movement that is forging its own canon.

More than 40 years after it emerged from South Bronx house parties, hip-hop has become a once-in-a-lifetime concussive force reshaping global culture. But at its most elemental and foundational, hip-hop is a direct, powerful confrontation with the built environment. “Broken glass everywhere / People pissing on the stairs, you know they just don’t care,” Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five rapped on their seminal 1982 track “The Message.” “I can’t take the smell, can’t take the noise / Got no money to move out, I guess I got no choice.”

From the jump, architecture inspired hip-hop. It’s poetry that bloomed in the shadows of housing projects, among the husks of burned-out high rises, and in view of subways tagged with a rainbow of graffiti.

But did the flow run the other way? Architects, academics, and artists like Nate Williams, Craig Wilkins, Amanda Williams, and James Garrett Jr. have written about, argued over, and wrangled with the idea of hip-hop-inspired architecture since the early 1990s. But after architect and professor Sekou Cooke held a symposium at Syracuse University in 2015, the discussion has intensified, culminating in Close to the Edge: The Birth of Hip-Hop Architecture, open at AIA New York’s Center for Architecture through January 12.

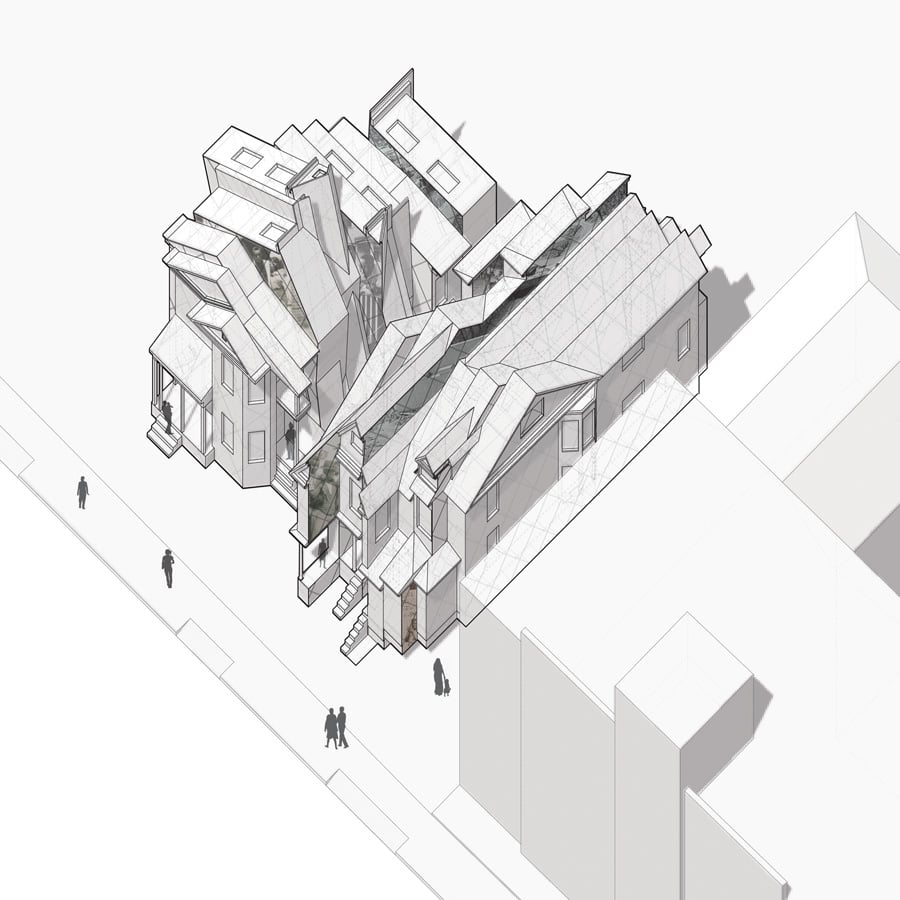

Curated and designed by Cooke, the exhibition is organized around three primary characteristics: hip-hop identity, hip-hop process, and hip-hop image. Mounted on panels from a deconstructed shipping container hung on graffiti-covered walls are proposals, 3D-printed models, photographs, and art created by 21 practitioners, academics, and students from five countries. Taken, together, they make the case for an international mode of design that is at once mature and still in its infancy.

“[Hip-hop architecture] has been translating into real-world building in a deeper way than I originally realized,” Cooke tells Metropolis. “I think more people are likely to acknowledge and accept that hip-hop is a space that relates directly to architecture. But it’s going to take a lot more work and a lot more time for it to become part of the canon of architecture. It might have to create its own canon before that happens.”

Close to the Edge is that canon fodder. Included in the show are requisite historical landmarks, such as Williams’ “This is my Nursery School,” a mixed-media collage that includes hip-hop lyrics scrawled over photographs of parking lots, billboards, and urban detritus. The work is drawn from her 1997 project There Are No Blank Sheets of Paper, considered one of the earliest examples of architectural thesis work to explicitly reference hip-hop.

Such pieces provide crucial context for the real-world (or soon-to-be built) examples of hip-hop architecture on view, like 4RM+ULA Architects’ JXTA Arts Center in St. Paul, Minnesota. Evolving out of a 2005 proposal, the planned four-floor, $3-3.5 million center for Juxtaposition Arts, estimated to be completed this year, boasts a polycarbonate exterior with dynamic LED lighting that can radiate in warm orange or cool blue or appear as a multicolor network crisscrossing—and tagging—the building.

The design grew out of 4RM+ULA founder James Garrett Jr.’s hip-hop obsession. He was drawn to architecture by his love of graffiti, and has written about and explored the nexus of hip-hop and architecture since college. “It was a cultural expression of who I was and what I was bringing to the architecture program,” Garrett says, and it eventually fueled his practice, from the low-budget/high-utility Magic Shed+Diamond Cloud project in North Minneapolis to the numerous proposals that came just short of winning contracts.

“Hip-hop kids are trendsetters,” Garrett adds. “We’re out there first on the vanguard of what the newest best practices are in our profession. When you’re on the front edge of something, people aren’t necessarily ready for it, and there’s a rejection when people are uncomfortable.”

Even as Garrett and 4RM+ULA met resistance, hip-hop architecture—like hip-hop itself—veined out from the U.S. In Haarlem, Netherlands, Boris “Delta” Tellegen, one of Europe’s earliest graffiti artists, designed a facade for a low-income housing complex built in 2013. Delta’s work resembles street art rendered in brick, a series of protruding parallelograms that animate an otherwise mundane building. And in Melbourne, Australia, Zvi Belling and his firm, ITN Architects, have drawn attention for explicitly injecting hip-hop into their projects, such as The End to End Building, an office complex completed in 2015 and topped with three Hitachi M-class trains—the canvas of choice for early graffiti artists—tagged end-to-end as they would’ve been in hip-hop’s formative years.

But ITN’s hip-hop reputation was forged by the controversial The Hive, an apartment building completed in 2012. Belling and artist Prowla incorporated graffiti rendered in concrete (along with angular and arrow-shaped windows) into the gray building, which many saw as a cynical, literal interpretation of hip-hop. When the Hive was shown at a lecture Cooke gave at AIA New York in 2016, it was met with boos and derision from many in the audience. “Graffiti is usually ephemeral—it’s only on the wall until another piece comes over it,” Belling says. “We wanted to play with that, with that idea of permanence. I guess we weren’t thinking about it in terms of literal. We were trying to think of it more metaphorically.”

Implicit in the criticism of The Hive is that Belling, a white architect, co-opted the spirit of hip-hop for the building—an assumption that speaks to a larger, existential question about appropriation and inclusion. In other words, who can practice in the hip-hop mode? The Hive “received quite a bit of negative response because people thought it was a little too on the nose, and I think the identity of the author was also being questioned,” Cooke says. “But I include it in the show just to open up that conversation. Because hip-hop architecture has yet to be ratified as a thing, it’s hard for us to say this is not it.”

At the same time, Cooke sees his scholarship (his next project is a book) as a way to give underrepresented communities an entry point into architecture. “The way that architecture is taught in schools is heavily dependent on a very Eurocentric, white, male point of view. So having alternative sources of information that actually speak to the people who are learning to produce architecture is very important.”

The confluence of hip-hop and architecture is ideally suited to accomplish that goal. At the opening of Close to the Edge, numerous visitors found themselves at the AIA center for the first time, attracted by the bizarre marriage of the two cultures. “It’s a bit more accessible when I hear ‘hip-hop architecture,’” Janay Anderson, one of those AIA newcomers, said. “I still need to do my research, but in general architecture’s not accessible to me. I think it can be in the right lens, and this seems like the proper lens to look at architecture.”

And in Belling’s case, it was hip-hop that helped inform his architecture. He has been immersed in Australia’s hip-hop scene for years, and it was his interactions with that community where he began to see the possibilities of bringing hip-hop into his projects. “I would have thought it impossible at the time that there could have been such a thing as a hip-hop architecture movement,” he says. “It was something I couldn’t even conceive of. So it’s very exciting that this has happened, that it has gathered this kind of momentum.”

Indeed, there was a sense at the opening of Close to the Edge that hip-hop architecture—for better or worse—is crossing over into mainstream awareness. Architectural historian and Center for Architecture board of trustees president Barry Bergdoll even went so far as to compare Close to the Edge to no less than Philip Johnson’s seminal 1932 Museum of Modern Art exhibition defining International Style. “This show, for me, is an historic moment,” Bergdoll said. “There’s a kind of vibe and excitement in the room that documents it. I hope [years from now] people will still be saying, ‘Remember that discussion at the Center for Architecture around the concept of hip-hop?’”

Cooke said he would never have made such a comparison himself—but it’s one he absolutely had in mind when organizing the exhibition. “That was completely intentional,” Cooke said. “I hope it gets debated and lectured about and talked about heavily, and then experimented with and tested on a global scale. Then, hopefully, 10 or 20 years from now, we’ll look back and say, this is a moment where architects decided to take on a different direction.”

You might also like, “Center for Architecture Unpacks the Legacy—and Unfinished Business—of Activist Whitney M. Young.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Finding Beauty in Climate Futures