March 19, 2014

How Migrant Workers Are "Silent Collaborators" in Global Architecture

Beyond Qatar, fantastic architecture is dependent on migrant labor.

A version of this article originally appeared on ArchDaily under the title The Indicator: Where the Migrant Workers Are.

Zaha Hadid’s unfortunate comments in response to worker deaths on construction sites for the 2022 World Cup has made Qatar the eye of a storm that has been raging globally for decades. But it’s not just about Qatar. This has been an issue for as long as there have been construction sites and for as long as poor people have swarmed to them for a chance at a better life.

Construction booms and migrant construction workers have always been two sides of the same equation, both dependent on the other, and, by the twisted logic of the global economy, both are the reason for the other’s existence. No migrant labor pool = no global city = no fantastic architecture, or something to this effect.

The migrant workers are the silent collaborators in global architecture, the invisible, faceless, “untouchables” who make the cost-effective construction of these buildings possible.

For decades there has been an unceasing flow of some of the world’s poorest citizens to the major construction sites connected with regional economic booms, Olympic games, and other nationalist or internationalist events. The venues for the recent Winter Olympics in Sochi were constructed by workers from Serbia, Bosnia, and Central Asian nations. Migrant workers are also flowing into Brazil as it prepares for next year’s World Cup. For this, workers are coming from Haiti, Bolivia, and even Bangladesh.

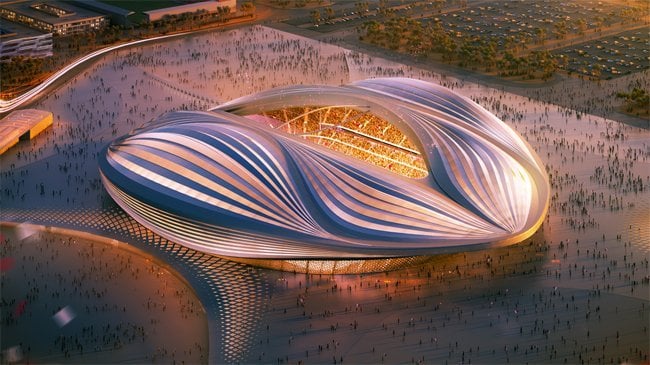

The al-Wakrah Stadium, designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, is currently under construction. Hundreds of migrant workers have died in the building of such stadiums for the 2022 Qatar World Cup.

Courtesy ZHA

According to Amnesty International, which has been tracking the plight of migrant workers globally, there are as many as 1.35 million foreign nationals working in Qatar alone, not all of them in construction but spread across different service sectors, including domestic work. In fact, in Qatar’s economy, 94 percent of the total workforce is made up of migrant workers. The workers come from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Iran, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Egypt. As Amnesty is trying to show, they have names, faces, families, and human rights.

How much of the world’s architecture is built by migrant workers? More specifically, how many examples of cutting-edge global architecture are implicated in the exploitation of some of the world’s poorest populations? These are good questions to ask.

More importantly, can architecture wield its influence to do anything to improve working conditions? Zaha Hadid doesn’t think so. But she, and other international architects working very visibly and publicly on landmark projects that attract the world’s attention, do have agency to influence stakeholders. In fact, eye-catching architecture could be the catalyst needed to draw attention to the migrant worker issue. This is an opportunity for architects, in partnership with international organizations, local governments, and clients to take a stand. Otherwise such buildings – rather than symbolizing the potential of our globalized world – will just be monuments to our big, global problems.

Guy Horton is a writer based in Los Angeles. In addition to authoring “The Indicator”, he is a frequent contributor to The Architect’s Newspaper, Metropolis Magazine, The Atlantic Cities, and The Huffington Post. He has also written for Architectural Record, GOOD Magazine, and Architect Magazine. You can hear Guy on the radio and podcast as guest host for the show DnA: Design & Architecture on 89.9 FM KCRW out of Los Angeles. Follow Guy on Twitter @GuyHorton.