October 22, 2019

New Exhibition Explores Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic Architecture—and the Slaves Who Built It

In “Palladian Models, Democratic Principles, and the Conflict of Ideals,” the uplifting content of early American civic buildings is offset by the reality of enslaved labor.

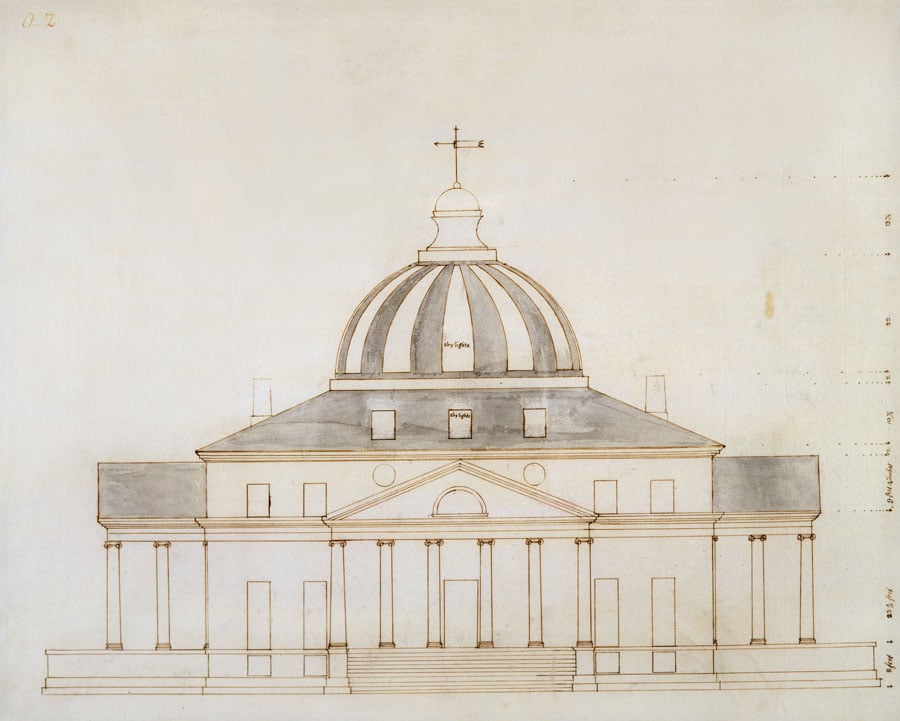

Courtesy Chrysler Museum of Art

Thomas Jefferson may have carefully studied the ancient Greeks and Romans, as well as the French, British, and Italian Neoclassicists—but it was Andrea Palladio’s books and drawings from the 16th century that influenced his architecture most.

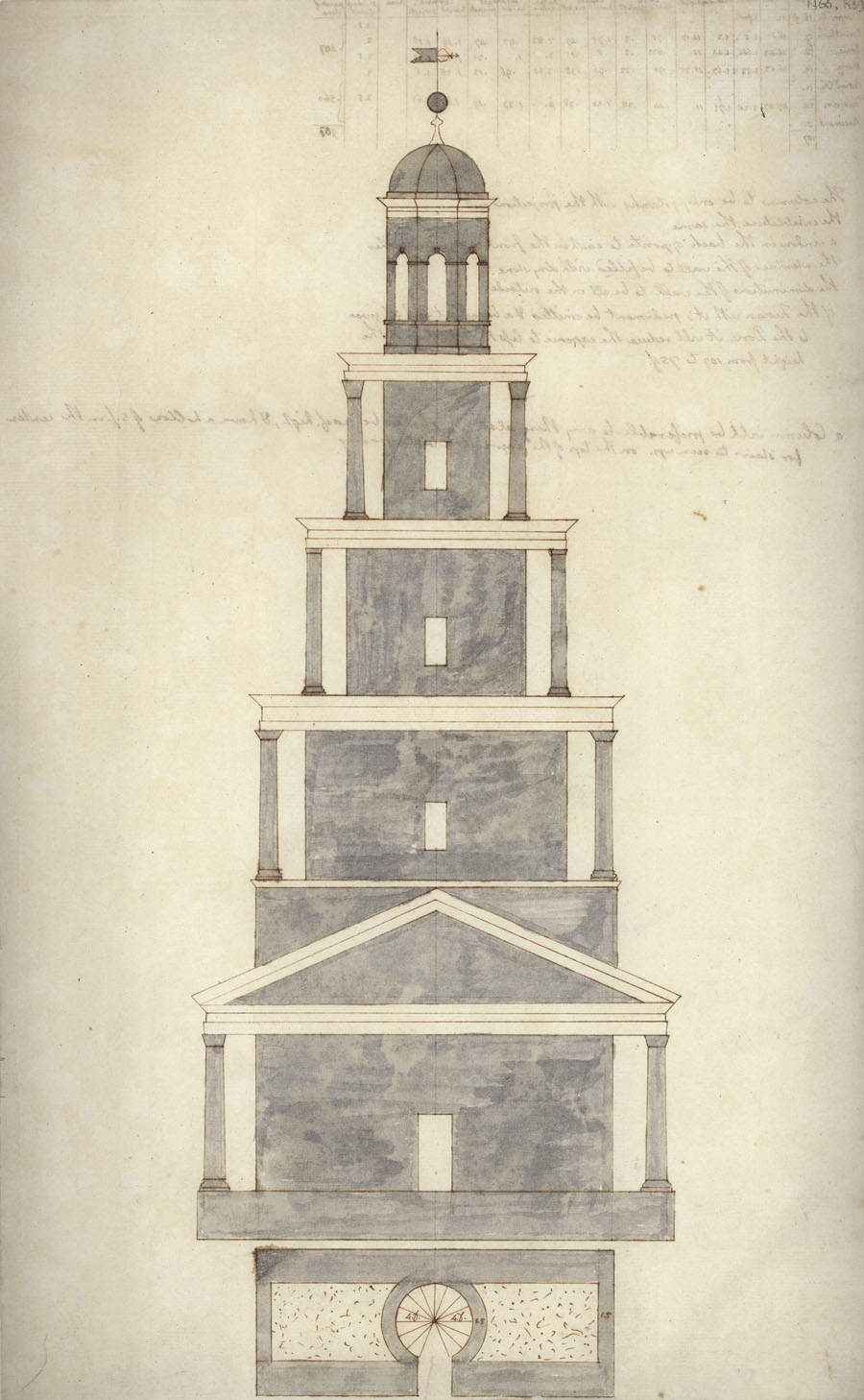

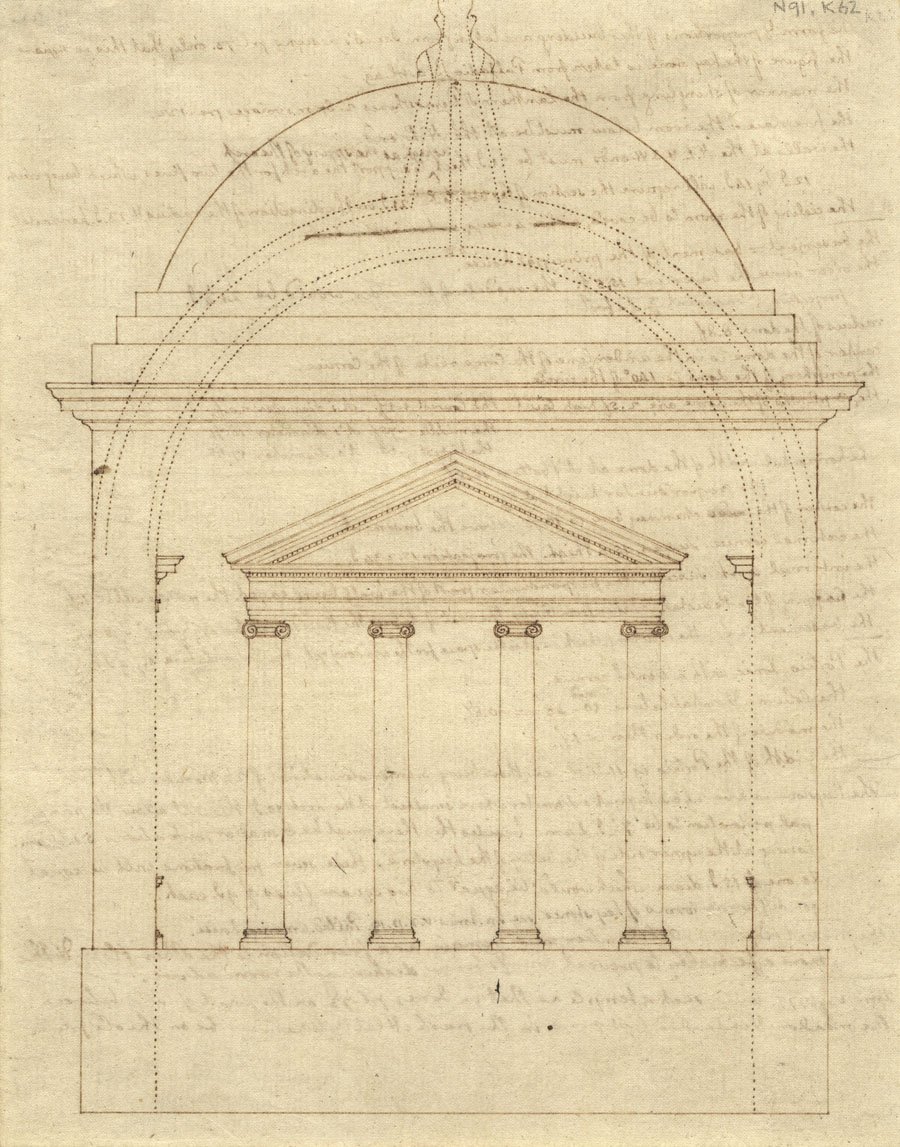

Thomas Jefferson: Palladian Models, Democratic Principles, and the Conflict of Ideals at the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia, sets out to examine all those influences through a nearly overwhelming array of material. Among the 130 items on display—objects that range from building maquettes to paintings and drawings—is a French volume of Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture, signed by the third president himself. Twelve models of designs by the two architects are on loan from the Palladio Museum in Vicenza, Italy. One is Jefferson’s entry for a 1792 White House design competition. It didn’t win.

“Jefferson is a fascinating figure—an American president who was also an architect,” says museum director Erik H. Neil. “That in itself is worth looking at.”

Courtesy the Maryland Historical Society

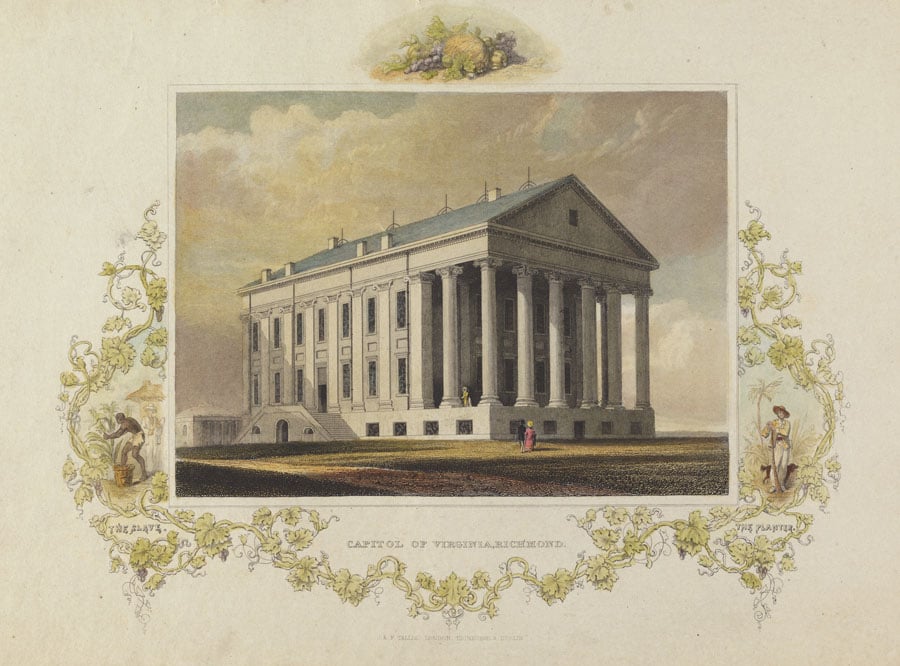

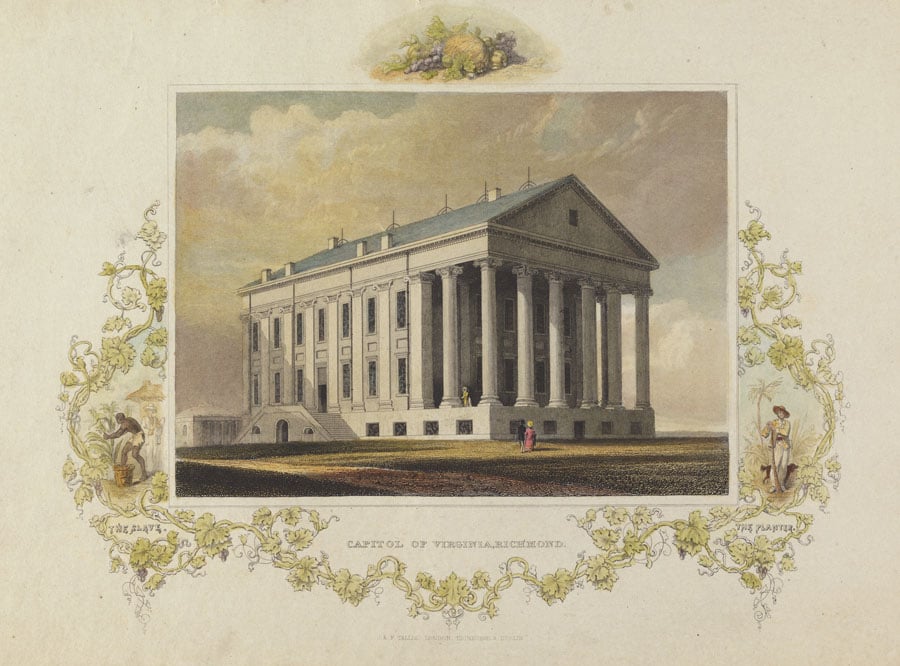

Crucially, the exhibition doesn’t shrink from a central contradiction: The uplifting symbolic content of civic buildings such as the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond or the University of Virginia in Charlottesville came at the expense of human freedom, as slave labor was responsible for both. How could Jefferson countenance the use of slaves in the construction of a democratic architecture?

The obvious answer: money. Much could be saved with enslaved labor, and more could be made by owners who rented slaves out.

It was not a new practice. The Greeks and Romans, whom Jefferson admired for government and architecture, had long histories as slave owners. “I think that it was generally understood,” Neil says. “There were physical and classical precedents for slavery—even in the Bible.”

Since their first arrival in Virginia in 1619, slaves worked at every level of Southern society. “It was an absolutely pervasive institution,” says Louis P. Nelson, professor of architectural history at the University of Virginia and author of the final chapter in the exhibition’s catalog. “You have to work really hard to find a building in the 18th century not built by slaves.”

Tracy W. McGregor Library, Accession #2041, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, VA. MSS 2041

Jefferson’s attitude toward this population is certainly disturbing. In his “Notes on the State of Virginia” from 1781, he concluded: “I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.”

Says Nelson: “He’s a white Virginian writing for an enlightened European audience. He was establishing Africans and African Americans as a lower category of humanity.”

As Jefferson designed his Academical Village at the University of Virginia, those attitudes were self-evident. Slaves building the university and cooking for professors were housed in basements with little light and cramped, damp conditions. Most slept in hallways; few had permanent quarters. “Jefferson was thinking about the power of the architecture, and not the accommodations of the workforce,” Nelson says.

Through his books and drawings—Jefferson never actually visited a Palladian villa—Andrea Palladio had enormous sway over architectural outcomes at Monticello, Poplar Forest and the University of Virginia. But as this show at the Chrysler reveals (with many of those same artifacts, plus nails and carpentry created with slave labor), the moral price for Jefferson was high.

You may also enjoy “RIBA Exhibition Tells the Oft-Neglected Story of the ‘British Bauhaus.’”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected].