September 20, 2017

From Monstrous to Marvelous, “Never Built New York” Showcases NYC’s Unrealized Ambitions

By considering the city’s unbuilt skyline, a new exhibition at the Queens Museum compels viewers to consider its future.

Architectural plans, as the process traditionally goes, are developed and disseminated, and then either built or not, for all sorts of reasons. While the projects that are built are usually better known than those unrealized, fame (or infamy) can follow either. Robert Moses’s plan for the Lower Manhattan Expressway, for instance, enjoys a much higher profile than the majority of nondescript buildings or parkways dotting the boroughs.

A new exhibition at the Queens Museum seeks to revive and memorialize nearly a hundred of these dashed plans for buildings, infrastructure, transportation networks, stadiums, and more developed for New York City over the years. In doing so, Never Built New York cultivates a fantasy city, one experienced across three of the Queen Museum’s galleries, that illustrates what could have been.

Based on a book of the same title, the show comprises aborted architectural plans, all mined by curators Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin. The exhibition’s first room, the Manhattan-shaped Rubin Gallery, displays a dizzying number of drawings, renderings, and news clippings on its walls and organized more or less geographically. Alternative plans for New York’s now-defining public spaces and landmarks abound, including a 1903 McKim, Mead & White design for Grand Central Terminal and a much-condemned 1985 Michael Graves expansion plan for the Whitney Museum of American Art. Other projects feel uncannily familiar, like Moshe Safdie’s modular and terraced Habitat New York I and II, a project Lubell deems “more radical” than its sister project, the iconic Habitat 67, developed for Montreal.

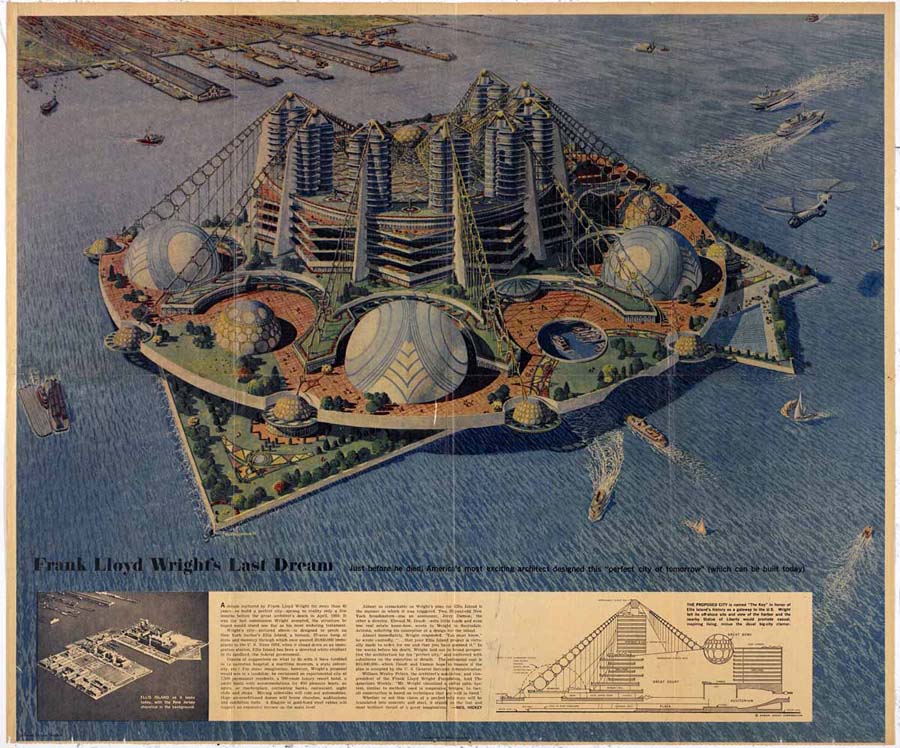

Still, others are completely fantastical. Projects such as Buckminster Fuller’s Dome Over Manhattan (1960) and Raymond Hood’s 50- to 60-story Skyscraper Bridges (1929), proposed for both the East and Hudson rivers, simultaneously reflect the misplaced optimism and technological constraints of the eras in which they were developed. Somewhat more feasible are Steven Holl’s 1990 Parallax Towers, a collection of super-slender towers rising from the Hudson River connected by horizontal bars; a 13-foot model of the project is a standout.

The exhibition continues into the circular hall containing the Queens Museum’s famed Panorama of the City of New York. Dozens of Never Built models have been installed on the giant maquette, “like ghosts placed all over” the locations they were initially intended for, according to exhibition designer Christian Wassmann. From this bird’s-eye view, the viewer sees how these projects might have fit into the urban fabric. A mirage of a fundamentally different city emerges, one where Robert Moses’s Brooklyn Battery Bridge and William Zeckendorf’s sprawling airport (1946) stretching across the Hudson River coexist, where I.M. Pei’s 108-story Hyperboloid (1956) straddles Grand Central Terminal. Virtual-reality headsets immerse the viewer even deeper into this alternative New York (mostly Manhattan), conveying the monumentality of Hood’s apartment bridges and the noise of Zeckendorf’s airport.

The third and final part of the exhibition is held in the Skylight Gallery, containing speculative designs for Flushing Meadows-Corona Park and, somehow fittingly, a bouncy castle modeled after Eliot Noyes’s plan for a 1964 World’s Fair pavilion. Between the panorama and the castle, children will have plenty to interact with.

While many of the wild schemes can evoke feelings of terror (at their destructive potential) or relief (at their not being built), the curators were careful to avoid making aesthetic or political judgements with their selections. Lubell explains that the duo opted to include projects that “would have fundamentally changed the city and things that would have an impact.” But, he adds, that doesn’t preclude them from having opinions about the material. “We can personally think we don’t like [a project], but if we thought it was important enough, we put it in the show.” This curatorial approach explains why more buildable projects are presented in the same manner as, say, Fuller’s fanciful city-sized domes.

There is a treasure trove of architectural work to marvel over. But the visuals should prompt more, Lubell suggests. By contemplating the city around them, visitors may begin “to think about what could have been, and to think about what could be.” Architecture and planning are dynamic and contingent processes; moreover,the urban environment that we occupy is not arbitrarily assigned or inevitable. The city is, and has always been, ours to reshape.

Never Built New York is on view at the Queens Museum through February 18, 2018.

You may also like, “Artist David Hartt Sifts Through the Ruins of Moshe Safdie’s Unrealized Habitat Puerto Rico.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Navigating the Path to Net Zero