January 30, 2018

The Devil Went Down to Georgian: An Artist Investigates Britain’s 300-Year Architectural Infatuation

In a new drawing show at RIBA, London-based artist Pablo Bronstein reimagines and reorients the ubiquitous Georgian-style building.

Pablo Bronstein’s exhibition at London’s Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), Conservatism, or the Long Reign of Pseudo-Georgian Architecture, is cunningly titled. It is a study of Britain’s 300-year attachment to the Georgian style of architecture, which means it is also a study of British conservatism. Yet there is also a hint of something entirely contemporary.

“Pseudo-Georgian” is the London-based artist’s term for the mostly developer-led architecture made ubiquitous over the last 40 years, the kind that sports the superficial motifs of the 18th Century style—sash windows, pilasters, rusticated stucco—in an effort to evoke the grandeur of the past, but often on the cheap.

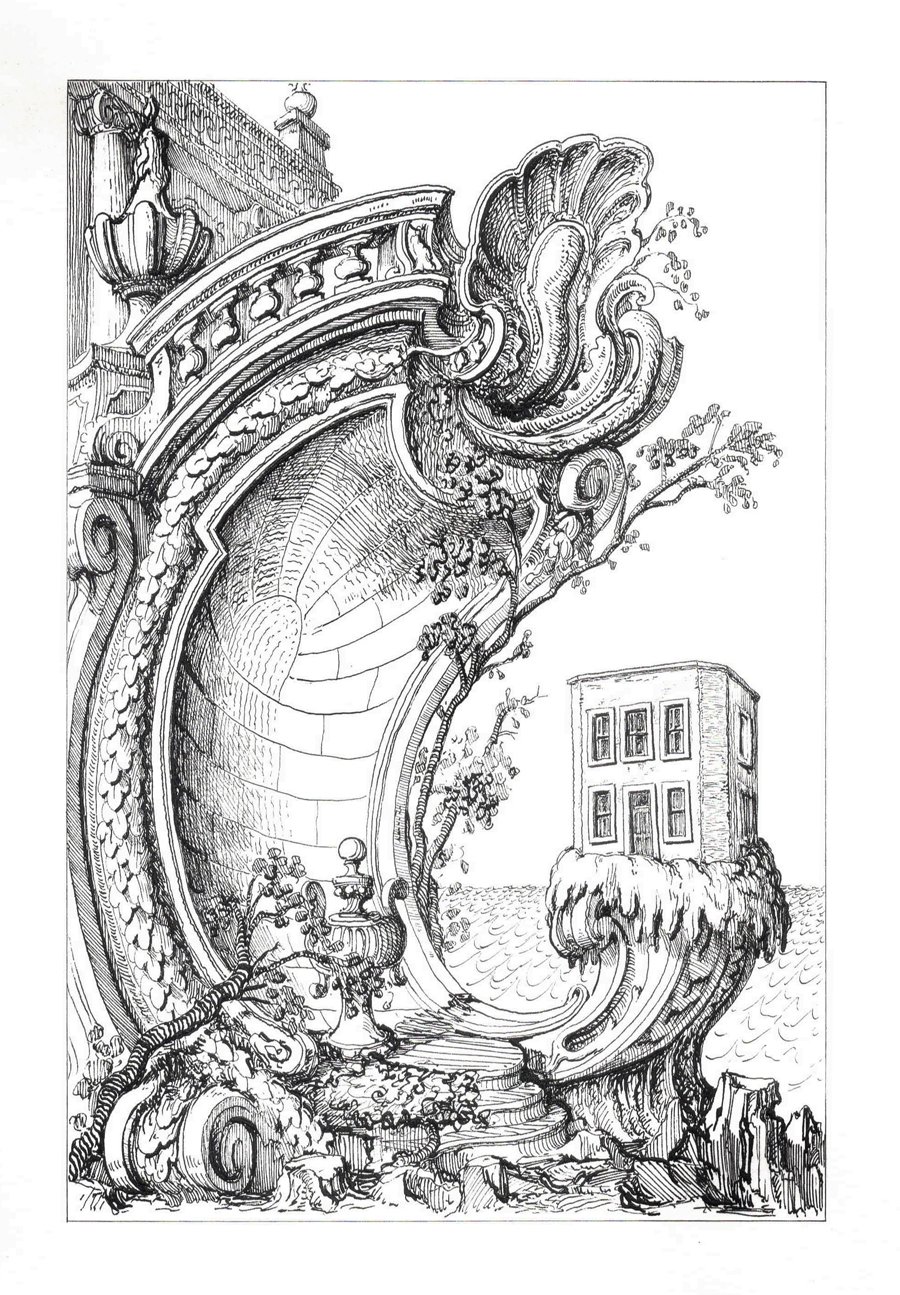

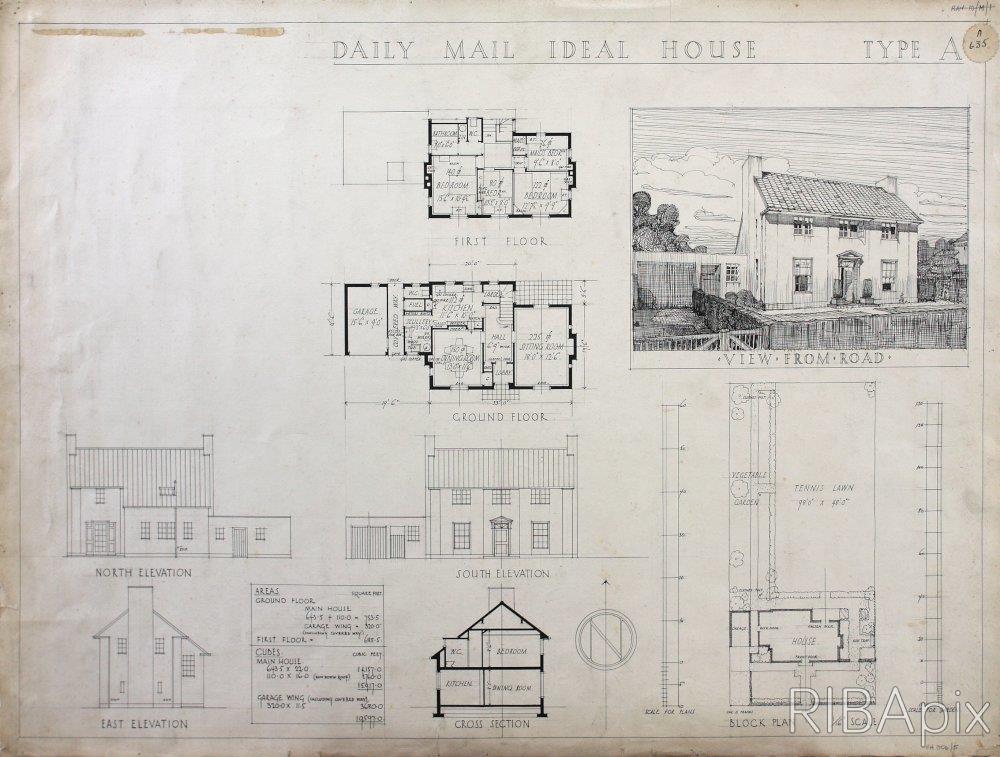

For the show, Bronstein has produced 50 pen-and-ink drawings of such buildings: individual houses with regency porches, office spaces that resemble mansions, retirement homes framed by grand arches, supermarkets embellished with dramatic arches and towers. They are displayed in a space styled in the manner of a pseudo-Georgian home interior, and are accompanied by the artist’s written commentary and historical documents.

Bronstein is particularly interested in the mistakes, redundancies, and creative embellishments that reveal a building’s inauthenticity—a decorative keystone, a dividing line in cladding, a suspicious uniformity. He has recorded these architectural details faithfully, burglar alarms and all, but has surrounded the buildings in fantastical framings of floral wreaths and ornate urns. The more humble the structure, the more elaborate the setting.

As a body of work, it could be read as a critique of the U.K.’s current post-Brexit mood, but, in fact, it’s more of a timely observation than a direct response. Bronstein started working on the drawings several years before the Brexit vote was cast. These pseudo-Georgian buildings, which he began documenting several years ago, “simply wanted to be thought of as posh,” he writes in a book about the series.

Still, the emergence of the Georgian style has an intriguing political backstory. The original version was born during the successive reigns of four King Georges between 1714 and 1830, at a time when the British Empire was strong and national confidence at a peak. European classicism gave way to a more understated aesthetic—more in line with British tastes.

Ink on Paper, 21 x 14 cm. Copyright Pablo Bronstein, 2017. Courtesy Herald St Gallery, London and Galeria Franco Noero, Turin

The style reasserted itself once again in the early 20th century as “neo-Georgian,” at a time when there was a Sterling currency crisis and Britain’s grip was loosening on its empire. Amid questions about national identity, this architecture seemed to represent the very idea of a strong and stable Britain. After the Second World War, in a country shattered by years of conflict, the neo-Georgian was ousted by Modernism—with its forward-looking, utopian ideals—as the vehicle for rebuilding the nation.

Bronstein’s focus is on what happened next: Beginning in the mid-’70s, buildings began to shift yet again toward a more traditional style. This shift was prompted by both the backlash against Modernist buildings after a series of high-profile accidents and the strengthening of conservation movements. Soon advertisements began to emerge that promoted the latest Corinthian capitals. And then in 1984, Prince Charles derided the proposed glass extension to London’s National Gallery a “monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend” and three years later revealed plans for Poundbury, a village in Dorset built in a traditional style. Both local authorities and middle-class families began to refurbish dilapidated old houses, while, over in the United States, movie stars and millionaires began to adopt classicist tropes in their homes, creating an aura of glamour around such architecture.

And so, the pseudo-Georgian was born. Volume housebuilders began to churn out buildings with paneled doors, tilting sash windows, non-functioning chimneys, and brick cladding. And the public consumed these buildings with relish, just as Margaret Thatcher’s 1980 Right to Buy policy privatized vast swaths of the public housing stock and kickstarted an era of mass property ownership and speculation.

Of course, there are perfectly good, practical reasons for the enduring appeal of Georgian architecture: large rooms, high ceiling, lots of natural light, and, for developers, the ease of replicating it at-scale. But it’s no coincidence that this traditionalist revival occurred against a backdrop of uncertainty. It was a time of rapid de-industrialization and in 1973, Britain joined the European Economic Community to stave off further economic decline. When Thatcher became prime minister in 1979, she ushered in an era of privatization, deregulation, and economic liberalization. A wave of nostalgia accompanied this period of rapid change.

Part of this exhibition’s appeal is in seeing this style—one that most contemporary architects would deride—in an august arena like the RIBA. Bronstein’s loving, romanticized drawings extract ordinary homes and commercial properties from their contemporary contexts and elevate them to the status of monuments, flaunting rather than hiding their inauthenticity.

But from this visual pleasure emerges a question: Is Bronstein mocking these buildings, and the parochial tastes of those who like it? And are we?

A lot of the artist’s comments on the buildings’ failures and eccentricities are laced with irony: describing a pre-cast cement lintel, inserted as a decorative ornament over a regular aperture, he says: “This mishap is a moment of absolute beauty and should be preserved for the nation.” But Bronstein is adamant that he’s not seeking to disparage this architecture—rather, he believes that its popularity and adaptability makes the pseudo-Georgian style, for all intents and purposes, a vernacular architecture and therefore worthy of our attention.

It’s certainly true that, while architects line up to defend Modernist estates, most of Britain’s cultural elite—architects included—choose to live in traditional houses themselves, suggesting that their tastes are more aligned with the wider public than they would like to admit. Perhaps, then, at a time when the country is again facing an identity crisis, accusations of snobbery stem more from the the fact that this exhibition holds up a mirror to the tastes and prejudices of us all.

You might also enjoy, “RIBA Tells a Tale of Two Londons: Why Mies Failed and Stirling Prevailed.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Navigating the Path to Net Zero