June 3, 2019

Baseball Urbanism: How Generations of Ballparks Have Shaped Cities, and Vice Versa

Paul Goldberger’s new book, Ballpark: Baseball in the American City, traces the arc of American urban history through the ballpark.

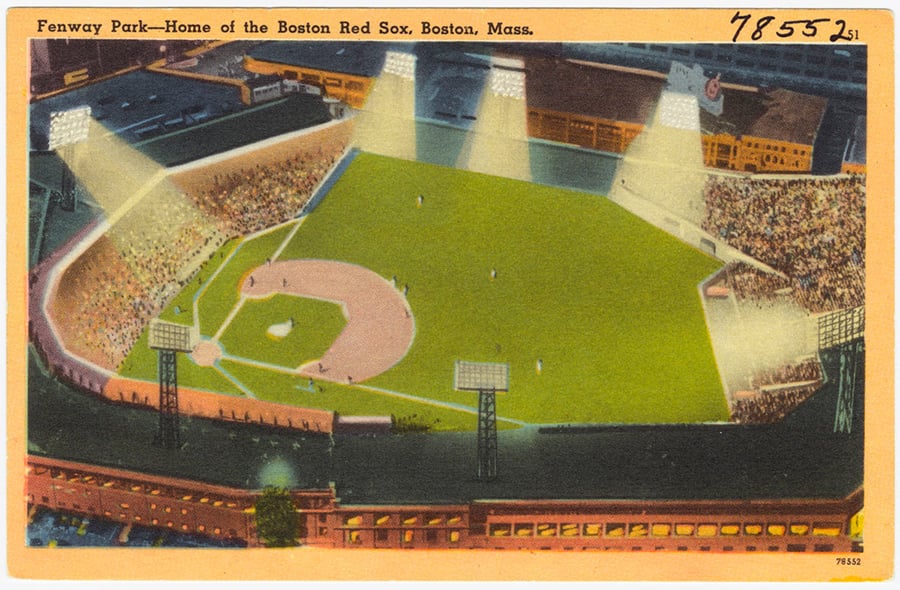

There are undoubtedly fans of Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum, in East Oakland, California, the way some people appreciate fatbergs or long-thought-extinct bacteria. But next to Boston’s Fenway Park (1912), Chicago’s Wrigley Field (1914), and Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium (1962)—masterpieces all—Major League Baseball’s fourth-oldest ballpark is the worst kind of concrete-donut-era relic. Opened in 1966, the stadium served MLB’s Athletics and the NFL’s Raiders, the latter of which took priority. It’s aesthetically blunt and cookie-cutter, and increasingly apocalyptic: Raw sewage spews into clubhouses while mice die in soda machines. And with the Raiders decamping for Las Vegas, there’s no longer a case—if there ever were one—for staying the Coliseum’s demolition.

Mercifully, the end might be near. In November 2018, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) released its initial plans (they were revised in February) for a new 34,000-seat ballpark on West Oakland’s waterfront. Scheduled to open in 2023, the retro-modernist building straddles “golden age” ballparks and Norman Bel Geddes’s streamlined aesthetic. It’s also the centerpiece of an Athletics-controlled micro-city that includes mixed-use housing, public space, a commuter gondola, and extensions of the street grid. (There’s also a separate BIG proposal to redevelop the soon-to-be-former coliseum site.) “We are honored and excited to team with the Oakland A’s to help imagine their future home where sports culture and local community culture unite as one,” Ingels said last year. “We envision a stadium district that will be active and inviting 365 days a year for athletes, fans, and Oaklanders alike.”

Ballclub-as-developer feels unnatural—baseball teams should be in the business of baseball. But as Pulitzer Prize–winning architecture critic Paul Goldberger writes in his new book, Ballpark: Baseball in the American City, such real estate impulses in the business of baseball aren’t new. Fenway Park, for instance, got its name because the Red Sox’s then-owners wanted to spur development to Boston’s Fenway. The venerable ballpark is iconic now, but a century ago it was an advertisement.

Goldberger’s book is steeped in this kind of history, contextualization, and reconsideration of spaces that often inspire passionate affinity and devotion. But at its core, Ballpark is an invaluable contribution to our understanding of and conversation about cities. “Nobody had really taken a serious look at these places as works of architecture or thought about them as urbanism,” he tells Metropolis. “The ballpark is a mirror that shows you the attitude this whole culture has had about cities since the mid–19th century to right now.”

It was crucial, Goldberger says, to establish “a single narrative of baseball and urbanism intertwined in American history.” It’s one that turns on a familiar axis: the Hamiltonian/Jeffersonian push and pull between urban and rural values embedded in the American experience. But unlike most political flashpoints, the ballpark represents the increasingly rare outcome of compromise. The building is pure Alexander Hamilton (a commerce-driven city within the city) and peak Thomas Jefferson (a potentially endless, lush, Technicolor-green field, if not for that pesky outfield wall). “In the baseball park, the two need each other,” Goldberger writes. “The structure of the grandstand exists to allow people to watch what is happening on the field, while the field exists to give the grandstand its purpose.”

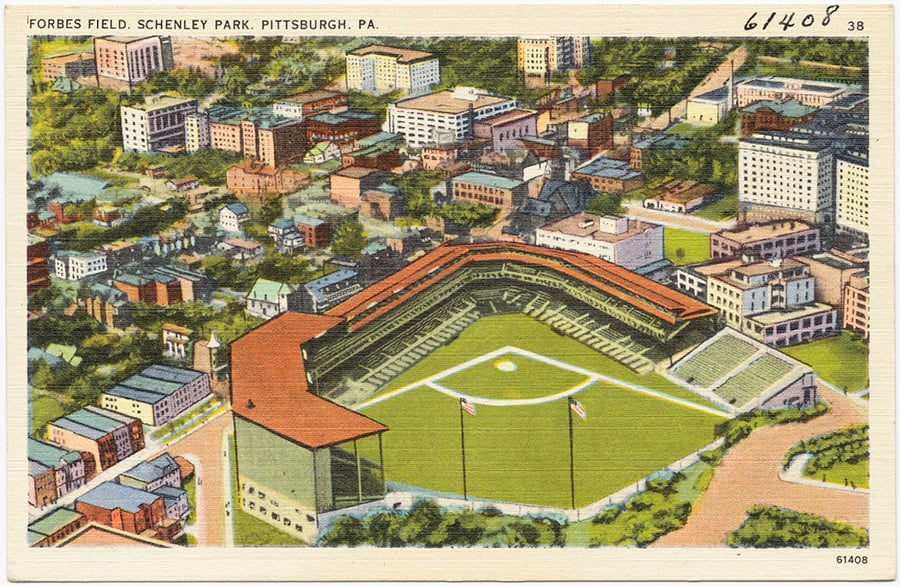

After tracking the prototypical wood (and very inflammable) ballparks of the mid–19th century, Goldberger identifies distinct eras of rus in urbe design. The first, the golden age when baseball was truly an urban game, gave us Fenway, Wrigley, and lost gems like Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field and Philadelphia’s Shibe Park—monumental architecture firmly enmeshed in the raucous, cacophonous early-20th-century city. Then came the postwar concrete-donut era, when the sport—and the country—suburbanized, and unique parks like Forbes and Shibe were replaced with characterless multi-purpose facilities marooned in parking lots (Three Rivers Stadium and Veterans Stadium, respectively). The retro-ballpark corrective came in 1992—with the first flutters of reverse white flight—when the Orioles opened Camden Yards in downtown Baltimore, perhaps the most consequential ballpark in MLB history. It forced a fundamental rethink of baseball’s relationship to cities and sparked an unprecedented building boom: Twenty-one new ballparks were built between 1994-2017.

Goldberger began Ballpark with those three eras as the framework. But while writing, he realized a fourth was beginning when the Atlanta Braves opened SunTrust Park in suburban Cobb County in 2017. A replacement for Turner Field, which opened in downtown Atlanta in 1996, the new facility exists within the “ersatz city” Battery Atlanta, an urban mirage established at the intersection of two freeways. “It’s the kind of disingenuous, fake city, not the real city,” he says. “It emerges out of the idea of the city as entertainment and the city as an entirely privately-controlled pseudo-public space. It’s a very different animal, and it parallels the way we’re viewing cities in general.”

SunTrust’s urbanoid planning model might seem new, but it’s an on-steroids version of a similar phenomenon found at other ballparks—even ones from the golden age. Chicago’s Wrigley Field, for example, has Wrigleyville, while and St. Louis’ Busch Stadium anchors St. Louis Ballpark Village. These homogenous entertainment zones have all the attractions of Any City, USA—characterless sports bars, chain hotels, name-brand retail—and little local flavor. As Christopher Borrelli wrote in the Chicago Tribune,“Since Opening Day [2018], [Wrigleyville] has felt like just another apocryphal non-neighborhood, damned without a there there.” Even their names evoke rural pastiche more than urban grit.

It’s an evolution driven by MLB’s market forces, especially flatlining-to-declining attendance. “Teams are all trying to maximize income, and some of it comes from trying to control what’s around the ballpark,” Goldberger says. Just as hypercapitalism has mutated urban neighborhoods into taxpayer-funded, monocultural fiefdoms of the super-rich (see: New York’s Hudson Yards), baseball’s max-profit impulse is rewiring the ballpark into an increasingly exclusive city within a city within a city.

“We’re building more than a ballpark here, we’re building a new neighborhood in this part of the city,” A’s president Dave Kaval has said about BIG’s Oakland project. But given the economic currents steering cities across America, there are some who, rightly, worry just what kind of neighborhood that will be—and who it will be for. The team has pledged to work with community groups on the project, but the city’s maritime industry has sternly opposed the plan, saying it would cost thousands of living-wage jobs at the site.“There’s no way for this project to proceed without doing irreparable harm to Oakland’s working waterfront,” Mike Jacob, vice president at the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association, told the San Francisco Chronicle in April.

It’s a valid concern. But Oakland and Atlanta point to a deeper existential angst for baseball fans and city lovers. Team owners are copycats, and there’s fear that a successful SunTrust will inspire a Camden-like rush of teams replacing their retro parks with theme parks. There are currently no new ballparks planned beyond 2023 (the Texas Rangers’ Globe Life Field), but the history Goldberger documents make such a generational turnover feel almost inevitable.

“Ballparks, for better or worse, reflect larger trends, and they’re doing that again,” Goldberger says. “Having a ballpark as part of a larger new development is not in itself necessarily a bad thing. But it’s potentially troubling.”

You may also enjoy “With Its Painstaking Restoration, Eero Saarinen’s TWA Flight Center Gets a Second Life.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Navigating the Path to Net Zero