June 30, 2021

The Case for a Public Design Education

The chair of City Tech’s Department of Architectural Technology outlines how public education coupled with direct personal experience is critical to equitable urban development.

Three student encounters at the Department of Architectural Technology at the New York City College of Technology, “City Tech,” incite my desire to make an impassioned argument for the need and relevance of public design education. I serve as the department chair, so I sit at a nexus of student experiences and many stories of desperation and trauma. The urgency with which I make this case, is fueled by their optimism and persistence. Channeling students’ experience and skills toward social and civic problems must be a priority for educators and professionals investing in the next generation of urban architects, designers, and planners. An affordable and high-quality design education is the starting point.

In my first encounter, a student came to my office and recounted the dramatic story of his family’s escape from the Syrian conflict. The second was a freshman in a foundations design class, a young Black man on parole. His instructor brought him to my office to ask: “Can we figure out ways to help him get through the semester? Because he’s trying to balance a whole lot, paying tuition while looking for stable work and maintaining his school workload. We don’t want to lose a student with his talents.” The third encounter was a student who came to express anxiety about submitting her studio work on time, as her family’s home had recently burned down. My head was spinning.

Their stories influence the urgent and often impolite questions I press upon colleagues. What motivates these students to continue studying design through the ordeals they face? If there is no affordable design education should we make an honest proclamation that design is a private and elite endeavor, with only minor allowances for the underserved? Should faculty tell our students not to bother with this course of study because there are limited opportunities for you? Is the industry prepared to invest in, nurture, and receive them? Will they experience a sense of belonging in a largely gender and race–homogenous profession? How long will their skin color and lack of elite credentialing make them feel like outsiders? Do their ambitions align with egalitarian principles espoused by architects and designers? Are they expected to conform or will the profession evolve?

A theme runs through the stories of our students, distinguishing them from typical undergraduate students of architecture. They often carry tragedy and responsibility without familial safety nets, professional guidance, or stress- free institutional support. The students trust that studying design will set them on a course of agency and self-determination, away from uncertainty and insecurity. They believe in a professional meritocracy, where skills and knowledge deliver access and opportunity. Listening to them, an ultimatum for academia and the architecture and design industry comes into focus. We are charged with fulfilling the “sacred promise” between educator and student in spite of many personal challenges and institutional deficits. Cultivating these students’ enthusiasm can unlock intellectual and leadership potential, revealing valuable skill and talent deployed in the service of inclusive economic growth and a renewal of New York City.

There are nine colleges with architectural programs in New York City. Only two are public. The City University of New York (CUNY) system represents a quarter of all colleges in the city. Reviewing public financial records, we can see that CUNY educates over 275,000 students with an operating budget equivalent to that of just one private university. The largest of its kind in the tri-state area, with over 700 undergraduates, the Department of Architectural Technology at City Tech is one of CUNY’s senior college programs. Eighty-five percent of students identify as persons of color; 58 percent come from households earning less than $30,000 annually; 25 percent work more than twenty hours per week. Their tenacity is extraordinary. In 2012, when Superstorm Sandy rendered many students homeless, faculty support extended beyond academics: They served as counselors and advocates—skills again demanded during the pandemic. Public programs such as City Tech suffer from a chronic shortage of funding and support from private industry and public agencies. When students exert so much energy on survival, they forfeit opportunities to network and develop professional skills. They miss out on formative experiences common to students at better-funded programs, or from more affluent families: traveling abroad, visiting landmark structures, and having professional exposure.

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) 2016 report on Diversity in the Profession of Architecture listed architecture’s notoriously low salaries as one of the main reasons for the “lack of minority representation.” Yet while low salaries are the norm for many architectural practices, a design education can be an entry to more complex aspects of the building industry, such as facade detailing and energy modeling, where resources are ample: The New York Building Congress clocked $55.5 billion of construction spending in New York in 2020 alone. Students proficient in the digital design technologies, advanced materials, and performance analytics that we teach find demand—and higher wages—for their skills. According to one college assessment metric, the Social Mobility Index (SMI), which measures the extent to which a college educates economically disadvantaged students and connects them to good paying jobs, City Tech and other CUNY programs consistently rate well.

However, focusing strictly on employment overlooks the full potential of each student. Specialization and competitive salaries, draws attention away from critical issues that require holistic design thinking.

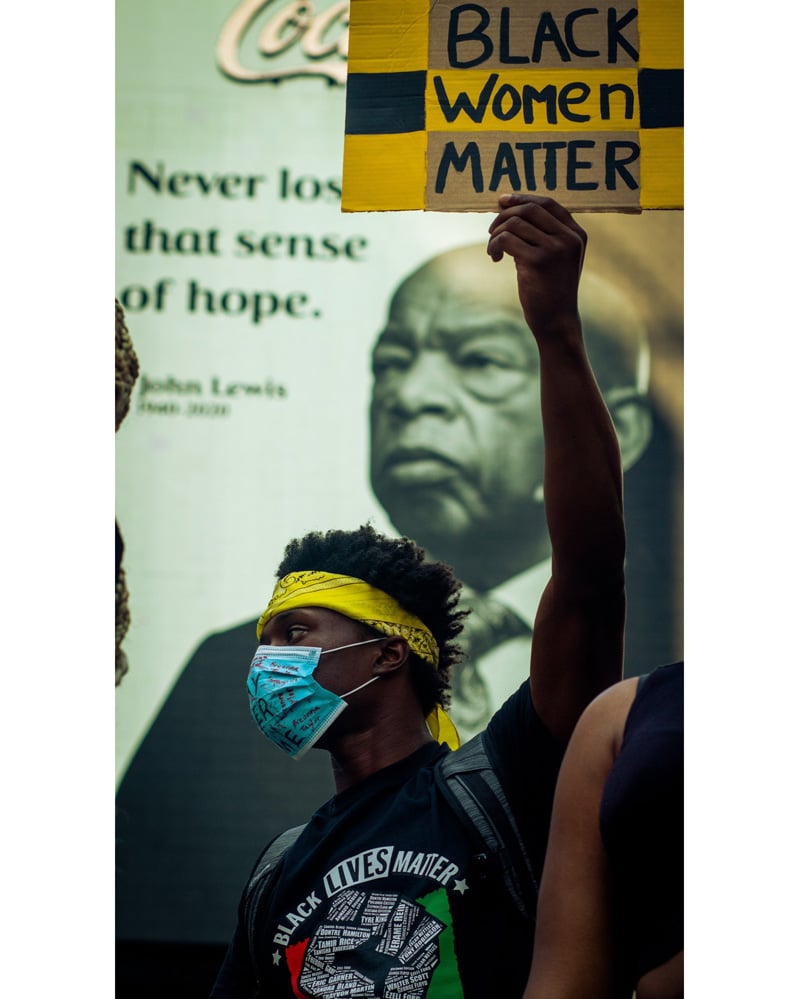

Public design education equips students with technical skill, historic knowledge, and aesthetic dexterity that can be applied to the design of buildings, spaces, and infrastructure. It establishes a pathway for human-centered planning and implementation that can provide equitable access to services, nature, and shelter—access to which many of these students have been deprived. Design education coupled with direct personal experience of the city’s deficiencies make these students important contributors to discussions on topics such as infrastructure and climate change responses. They can become effective advocates for their communities with firsthand experience of inadequate public services and knowledge of how design can be wielded to care for the aging and dying, support for the mentally ill and disabled, and accommodation for the homeless and formerly incarcerated. Their education is an act of self-defense. It is a defiant assertion of belonging and pride in diversity. An effective design education links aesthetics with science, policy, and human need. Vitruvian principles for the 21st century.

Private colleges, by contrast, stock private practices, which in turn provide funding streams and endowments, tilting urban development and the industry toward exclusivity and privatization. Graduates of private architectural programs often incur staggering debt that restricts their career choices. Tuition at City Tech is $7,000 a year, but graduates often lack access to professional networks. Their employment options are frequently confined to limited technical roles. Graduates from both private and public programs are therein hamstrung in applying their skills towards public service.

Nevertheless, our department endeavors to train technically proficient and engaged citizens who can advance from marginal positions of survival into real urban leadership. As an example, Percia Gomez, a 2019 graduate, worked for Councilman Ritchie Torres’ office, using her architectural education to advocate for her community. Hercules Reid, a 2017 graduate, is now an assistant to the Brooklyn Borough President and mayoral candidate Eric Adams. The two recognize that civic engagement underpins inclusive economic growth and is a precursor to the public’s appetite for design thinking.

The case for public design education is guided by the following principles. First: The built urban environment tethers the fate of the wealthy to that of the underprivileged; discounting one for the benefit of the other imperils both. Second: An alliance between schools of architecture, public agencies, and private practices is needed to foster technically proficient stewards and diversified urban leadership. Former US Commissioner of Education Ernest Boyer reported this as the “scholarship of engagement, connecting the rich resources of the university to our most pressing social, civic, and ethical problems.” Great ideas and great designs do not materialize in a vacuum. By properly equipping and empowering our students, their cultural knowledge, urban experience, and design talents can be fused into a superpower for a positive and inclusive transformation of the great City of New York.

This article originally appeared in Issue #20 of New York Review of Architecture

You may also enjoy “On this Fourth of July, Remember that Public Space is Democracy’s Great Stage”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]