November 10, 2010

Q&A: George Ranalli

On November 18th George Ranalli will receive the prestigious Sidney L. Strauss Memorial Award for 2010, from the New York Society of Architects. Dean of the Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture at City College, Ranalli also practices architecture in New York City, where he grew up. Since 1950 the award has been given to […]

On November 18th George Ranalli will receive the prestigious Sidney L. Strauss Memorial Award for 2010, from the New York Society of Architects. Dean of the Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture at City College, Ranalli also practices architecture in New York City, where he grew up. Since 1950 the award has been given to such important figures in architecture and urbanism as Ada Louise Huxtable (1970), still the strongest and most thoughtful voice in architecture criticism (now at the Wall Street Journal); Robert Moses (1976), the powerbroker who built modern New York; and Robert A.M. Stern (2004) who was instrumental in making us aware of our rich architectural history (now dean of architecture at Yale). Knowing about George’s meticulous preparation for everything he does, his ethics, his interest in history, his love of craft, and his attachment to New York City–all of it somehow related to his commitment to Modernism–we wanted to know what he’s thinking as his big day of celebration nears.

Susan S. Szenasy: So, George, in thinking about the amazing company you’ll keep as a Sidney L. Strauss Memorial Award recipient, as a long-standing architecture dean at City College, and as head of your own architecture practice, what goes through your mind as you make notes about your acceptance speech?

George Ranalli: I am very honored to be in such illustrious company. Although the past honorees do not fit into one ideology, they can variously be described as free spirits, visionaries, and pathfinders. That’s not bad company.

You are very kind to ask me what has been going through my mind these days. My mind has been filled with oscillations and analogies. In my own architectural practice and as the dean of a school of architecture, I continuously think about balancing innovation and stability, often on my walks to the office in Manhattan’s flower district. The place where I practice is in a loft building on a street filled with hustle and clamor. Merchandise spills from doorways, pots of trees line sidewalks. Trucks park in the middle of the streets, and dozens of workmen shout in different languages. The flower district reminds me every workday of a city that stays the same as much as it changes, and that balance is what I am always seeking to find in my work.

As the dean of a school of architecture, my thinking about how to educate the next generation of architects is probably more divergent than that of many educators; at the same time, the architectural education at my school stands solidly on the traditional mission and vision of City University of New York. At school-wide gatherings, the faculty and students gather to pledge service to the city. It is a key positive moment of every school year for me.

I am a modernist architect who loves to fold architectural history into the process of making architecture. I never think of creativity and consistency in an inverse relationship. When things go well for architecture, the work is always a substantial, craft-intensive, meticulous balance between the old and the new. This is what moves the architecture field forward. Architecture is an exciting phenomenon because the momentum never reaches an end point; rather, the synthesis becomes the next thesis, until architecture takes another step forward.

SSS: It is no accident that when Mildred Friedman asked you to curate the Carlo Scarpa show at CCA in 1999, she also asked you to design the installation and build the models for the show. You have had a life-long conversation for Scarpa, during his lifetime and seemingly posthumously. How much has your work, at all scales, been influenced by Scarpa? Are you continuing, and evolving, his famously enigmatic symbolism?

GR: Actually, it was Frank Lloyd Wright who made me first want to become an architect. The moment of clarity came on a Sunday evening when I was about thirteen-years-old. My father was driving the family through Central Park. I was dozing in the back seat. Then suddenly, through the trees, there was the Guggenheim Museum. It was still under construction, surrounded by scaffolding. In the half-light of dusk, the building had an incredible presence. I had never seen such an amazing sight! This is my earliest memory of an exquisite building paired with the excitement about construction and, of course, the beginning of my life-long enchantment with modernism.

As a fledgling architect, Scarpa’s work exercised an incredibly powerful influence on me, especially his methodology. In 1998, Mildred Friedman and I made a wonderful trip to Scarpa’s archive to research the CCA show, more than twenty-years after my initial accidental pilgrimage to Scarpa in the late 1970s. Having recently completed my graduate studies, architecture seemed adrift. At the time, American architecture was all about metal and glass, even though Louis Kahn had designed amazing buildings, from simple materials, like brick and concrete, into striking geometric, luxuriously textured, light-filled forms, which were so compelling to me as a student.

I wrote a travel grant, which afforded me the opportunity to research stone and masonry construction in European buildings. By 1976, I was traveling through Italy researching masonry construction. The highpoint of a visit to a Milanese furniture factory had been a newly fabricated table, made from large layers of hefty plywood and a gorgeous, ebony top. The chief designer conducting the tour explained that an Italian architect, I had most likely never heard of, had designed the table, which was about to be shipped to the owner. Shortly afterward, my colleague pointed me toward Verona, and the work of an Italian architect, Carol Scarpa.

The work by Scarpa in Verona marked my introduction to ingenious contemporary design within the fabric of an ancient city, and it was nothing less than a revelation. I was certainly “young” then, compared to Scarpa, but I trusted that my own eyes had found something very special. Encouraged by my colleague, I arranged a visit to Scarpa’s studio in Vincenza. I had expected to find myself in a prestigious architecture studio. Instead, I had arrived at Scarpa’s home. He was dressed in a black smock, and he looked like a quintessential European artist. What’s more, he was a modernist architect living in the carriage house of the Villa Rotonda, which was built in the 1500’s.

Scarpa’s office was even more of a surprise. Located in the cellar—more like a catacomb—the drafting desks were nestled into a space created by spindly stone columns. It was an exceptionally beautiful old room, but I kept saying to myself, “We’re in the basement of a carriage house.” Scarpa and I spent the day together, and we continued our discussion into the evening. His wife invited me to stay for dinner, and it was then that I found myself sitting at the same ebony table I had admired weeks earlier at the Bernini factory in Milan.

SSS: One of the most memorable aspects of your work is your use of light and how surfaces reflect and bounce this ephemeral (and yes, we can say, spiritual) builder and revealer of space. In your candid judgment, which of your works is the most successful in rendering that special quality of light you’re after? What makes it so?

GR: Light is an essential component in the formulation of buildings and interiors. I always employ light –natural and artificial –to enhance space for its occupants. We can look at these phenomena through the example of the Saratoga Community Center in Brooklyn, New York. On the building’s exterior, the movement of light across the recesses and framed elements accentuates the building’s mass, and therefore its resilient durability. Ornamental elements encased in the mass also define the outer edges of the wall as it meets the sky. The overall experience is a variable kind of vibrancy around the larger volume of the building in its place on the street.

Saratoga Community Center, Photo: Paul Warchol.

Saratoga Community Center, Photo: Paul Warchol.

The interior, by contrast to the exterior, is a light filled volume allowing natural light through carefully placed irregular openings in the masonry. Windows were arranged to capture the maximally positive atmospheric effects of daylight. The shape of the ceiling inside and the artificial sources of light, set in the delicate openings of the surface create another kind of special effect after sundown. The design elements befit the various events that take place in the large room. The daytime functions involve recreational programs for young children, teenagers, and senior citizens. On weekends, community members use the room for special events and celebrations, such as weddings, birthdays, anniversaries, and holiday parties. The quality of light is an essential ingredient to achieve the different atmospheric qualities supporting all these activities and occasions.

Saratoga Community Center, Photo: Paul Warchol.

Saratoga Community Center, Photo: Paul Warchol.

Our most precious memories of special events are usually organized around our experience of the physical qualities of the spaces that resonate with the heightened positive feelings about a wonderful time of life or a special day. Building interiors, especially the interiors of public buildings, either support or hinder the construction of key positive life experiences. I am very gratified to hear from the community about the ways in which the physical environment at the Saratoga Community Center reflects and enhances their personal experiences there.

SSS: Your architecture, as well as your small scale works like door handles and furniture, have a kind of handcrafted quality to them, but they are also very industrial in their material and form. How do these small-scale objects symbolize or reflect your architectural thinking?

GR: Design objects allow materials to be the star of the show. When I design an object, I do think about weight, heft, texture, natural colors, and other intrinsic qualities of materials. Form is equally important. A familiar object, in an unfamiliar form, engages people in particularly interesting ways. Materials tie form and design together.

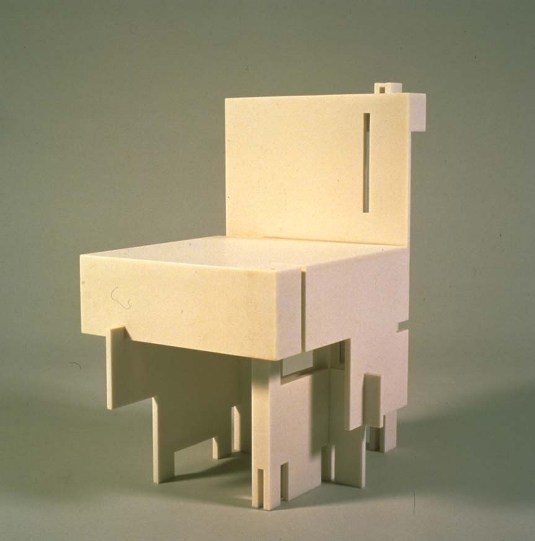

Valentine Chair # 2, Photo: Richard Barnes.

Valentine Chair # 2, Photo: Richard Barnes.

One example is my Valentine Chair # 2. This chair a reconsideration of the use of a building material, typically a flat surface finish, to make a chair with an atypically complex, luxurious, comfortable, geometric form. The Valentine Chair # 2 does not have a stereotypical form, making it difficult to categorize as anything other than modern. Although it also nudges the expectation that modern furniture design is spare. When I design an object, I think about decorative modernity, which is form that is functional and decorative through the innovative use of complementary materials. This process is exciting to me because it offers me as a designer the opportunity to incorporate what is often an optimal amount of novelty into everyday experience.

SSS: If a master builder like Robert Moses were around today, what would you tell him about building 21st century New York?

GR: My home, with my wife and two children, for the past thirty years has been in the same old lower Manhattan neighborhood, on the same block, in the same old apartment building. We share a deep affection for home, which begins with our neighborhood, and then moves to our block, then our building, and finally our apartment. Our neighborhood is uniquely special for many reasons, including its status as an epic social and political battleground.

In 1960s Mr. Moses advanced the idea of urban renewal, which meant bulldozing so-called “blighted” areas, enormous high-rise rebuilding, and ever-expanding highways. Mr. Moses became a rapidly spreading trend. Ms. Jacobs said, “Stop” by arguing a completely different view of the same city districts, she described as appealing, complex, socially vibrant places full of self-rejuvenating, and self-sustaining potential through community development, neighborhood rehabilitation, and historic preservation. Mr. Moses talked about what cities did badly. Ms. Jacobs pointed out what cities did well.

The skirmishes waged by New York’s most articulate, energetic civic activist Jane Jacobs against New York’s most formidable planning czar Robert Moses, over proposals like the lower Manhattan Expressway, took place right outside my front door. The debate inspired large numbers of everyday New Yorkers to participate, and when the dust settled, people had an understanding of urban economies and ecologies, and a lasting interest to participate in local planning and development—a newfound wisdom about the nature and functioning of cities.

These days, neighborhood and community altering proposals continue to come forward – and it happens quite regularly–the process is not what it was before the great clash of Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs. There is no large-scale visionary planner or master builder like Robert Moses, and this speaks volumes about 21st century New York City. The city has become an ascendant composite of progressive zones offering more of something for everybody, since more of everybody participates in the process. As New Yorkers shift away from old ways of living and reasons for living that way, like the automobile culture of Mr. Moses’ projects, toward citizen-led community groups of bicyclist, historic preservationists, and community environmentalists, local people remain involved in a public process. And their architects consider how a project, through its qualities of design, fits into an existing commercial, cultural, and residential activities, and at the larger scale, what is the lifecycle of a building, particularly its uses or misuse of materials and energy. Now, architecture has even more potential to reflect, enhance, and facilitate 21st century New York City life by contributing more fully to the genuine expression of the city’s interesting and delightful diversity as a human setting.

SSS: As dean at the Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture, what are your students teaching you about the future of the architecture profession?

GR: The students of the Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture are outstandingly successful young architects. Some have been recently selected as one of twenty finalist groups to compete in the U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Decathlon. The City College submission for a solar roof pod is unique for its adaptability to urban rooftops, and it is a beautiful, environmentally innovative idea. Given that the surfaces of buildings in cities retain the sun’s heat and create urban heat islands that as the EPA estimates may increase the city’s average air temperature by 1 to 3 degrees Celsius as the expected one-million-plus new residents settle here, the students have innovated an idea for an increasingly urgent environmental problem. Our newly launched student architecture journal, Informality, was recently awarded as a student architecture publication by the Washington DC Chapter of the AIA. These are just two ways to illustrate my undeniable opportunity to learn from my students.

The most important lesson, as always, is in the medium. City College students teach me about the advantages of a public school architectural education that cultivates competence, knowledge, creativity, principals of best practice, and innovation in a school setting that is one of the country’s most diverse. Thomas Edison remarked, “Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.” No one even disputes this statement, but people tend to focus on inspiration.

My students remind me every day about the hard work of making architecture: the work of tolerating ambiguity, categorizing concepts broadly, defining and redefining challenges, uncovering the heuristics of novel ideas, making decisions, and expressing complex ideas clearly, simply, and convincingly.

My students astonish me with their intellectual vigor and curiosity, their civic mindedness, and their tenacity for social justice. As they near the end of their schooling, they develop a passionate love for the work, affirming, over and over again, that the labor of love aspect of architecture is very important. After all, what’s more appropriate for a Modernist architect who loves history than to nurture architecture’s future to embrace its past?