September 9, 2020

Design Before Air Conditioning Surveys Early Experiments in Climate Control

In a new book, Daniel A. Barber details a climate-focused account of Modernism, one defined by increasingly blunt measures used to combat heat and humidity.

It’s easy to think of Modernism as inseparable from air conditioning, simply because we are surrounded by so much of it that is. A valuable reminder that this wasn’t always the case is provided in University of Pennsylvania architecture professor Daniel A. Barber’s Modern Architecture and Climate: Design Before Air Conditioning (Princeton University Press), which outlines the story of the febrile, flexible, and often-forgotten early experiments in climate control.

If Modernism became environmentally callous with time, he shows, it wasn’t so at birth. For a real sense of the discarded environmental sensitivity of early Modernism, contrast whatever curtain-wall building is nearest you with the innovative riot of Le Corbusier’s Immeuble Clarté. The latter, as Barber writes, features “a collection of low- cost, user intensive, and visually dynamic sun-shading devices: balconies, external blinds, retractable awnings, and interior shutters blocked and modulated solar incidence.”

Barber’s framing of Modernism through the lens of climate sensitivity links a number of architects who are rarely clustered in more aesthetic analyses. Connecting Le Corbusier with Neutra, Sert, and Schmidlin unsettles familiar taxonomies, in its linking of architects not because of how their buildings looked but how they paid close attention to the invisible demands of climate.

A common quandary for early Modernists was how to make large expanses of glass do more than just enable a view, given that glass was often a dud both at heating and cooling. “Familiar architectural means to manage solar radiation, and to more generally use architecture to condition space, were confounded,” Barber writes. Corbusier worked ceaselessly on this problem in many projects beyond the Immeuble Clarté, experimenting with materials, deepening and altering facades depending on their sun exposure, and most importably designing a profusion of brise-soleil. Louvers emerged as an easy, user-operated solution, both useful and conceptually revolutionary: a climate-control mechanism literally expressed on a facade.

Brazilian architects such as Lucio Costa and MMM Roberto played a pioneering role in refining such methods, and the State Department’s Office of Federal Building is described as one laboratory for environmental sensitivity, including some very effective projects, such as Sert’s work in Iraq, and some ineffective gestural nods, such as Durrell Stone’s embassy in New Delhi. Elizabeth Gordon’s climate-sensitivity encouragements at House Beautiful also make an appearance.

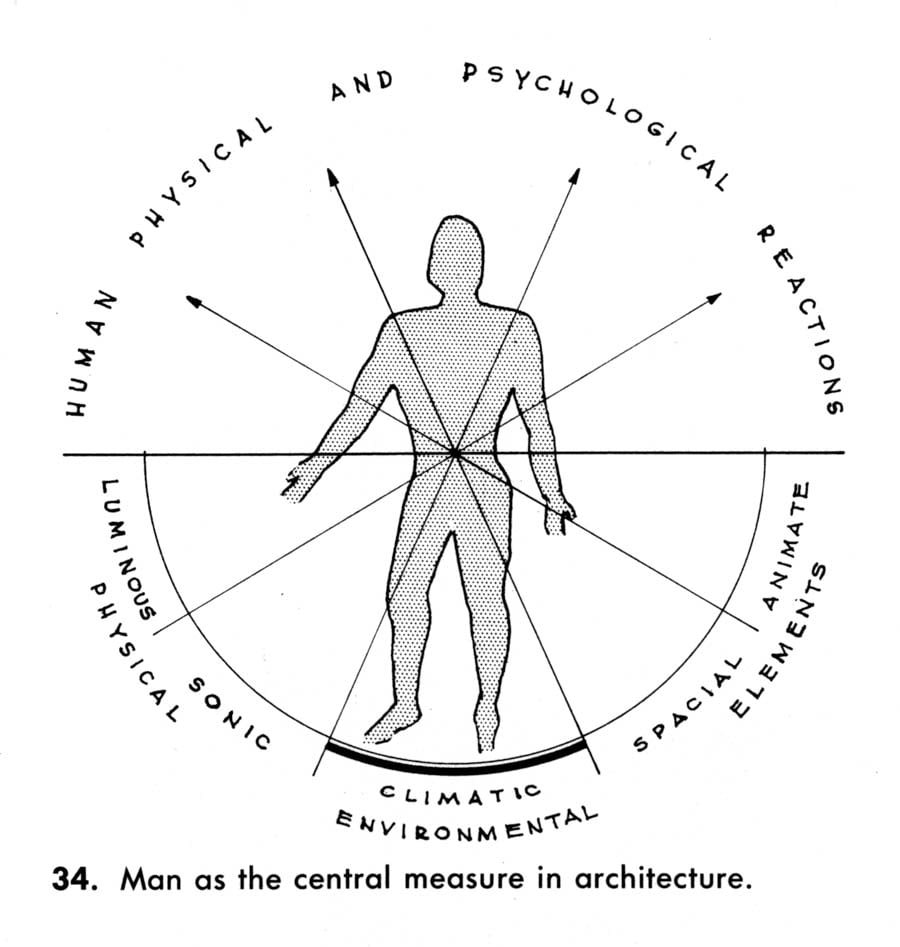

The book’s parallel story focuses on the nature of the interiors that walls seal off, homing in on the labors of early experts to quantify how to best deliver consistent temperatures in the face of the earth’s changing stew of heat and humidity. Much of the spirit of Modernism, Barber says, became degraded to producing “a consistent interior across different regional, cultural, climatic, political, and economic conditions.”

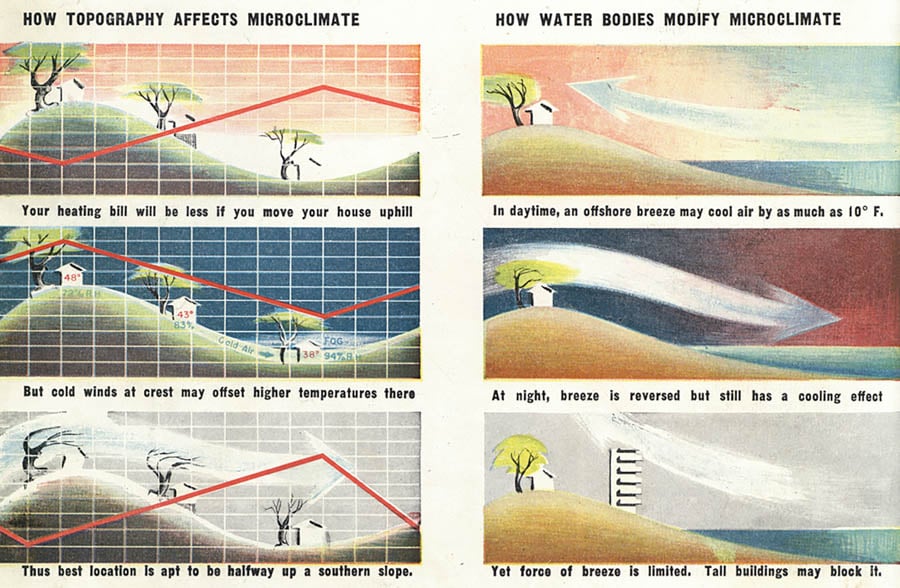

Barber pays homage to a number of unsung meteorologists and scientists churning out charts on tree placement and sun angles at different times of day, variables of climate related to slopes and proximity to water, and more. The trouble with any such modeling, extremely well-intentioned, was that climate is intrinsically and inextricably ultra-local, and many architects opted to just give up.

Why? For one reason: cheap air-conditioning, a blunt tool that could deliver the same interior temperature to the most climatically inept building, provided you could pay the bills and didn’t care about the fossil fuels spent. Climate mitigation design efforts, that resembled traditional ships’ rigging in working with nature, were left to eccentric hobbyists or the benighted, as air conditioning swept all before it as surely as coal-fired steamships.

Curtain walls, with their staggering inefficiency, became de rigueur. The United Nations building’s cooling system was famously inefficient; the Seagram Building is an impeccably tailored but ludicrously unhealthy Mad Men–era sybarite (in a recent Manhattan energy audit, it received a grade of 3—on a 100 point scale—“the lowest grade given, by a wide margin.”

The trouble, as we have realized, is that uniformly cooled interiors bear a weighty responsibility for a warming world; in our present reality 40 to 60 percent of carbon emissions are produced by buildings. What to do? Barber stresses we must look to the past—and we needn’t even go so far back.

You may also enjoy “A New Book Highlights Tom Kundig’s Nature-Driven Process Through Recent Projects.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis Webinars

Connect with experts and design leaders on the most important conversations of the day.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Navigating the Path to Net Zero