September 17, 2013

Three Architects on the Most Valuable Design Skill—Listening

The best outcomes on a project may have less to do with ego, more with the fine art of paying attention to what’s said

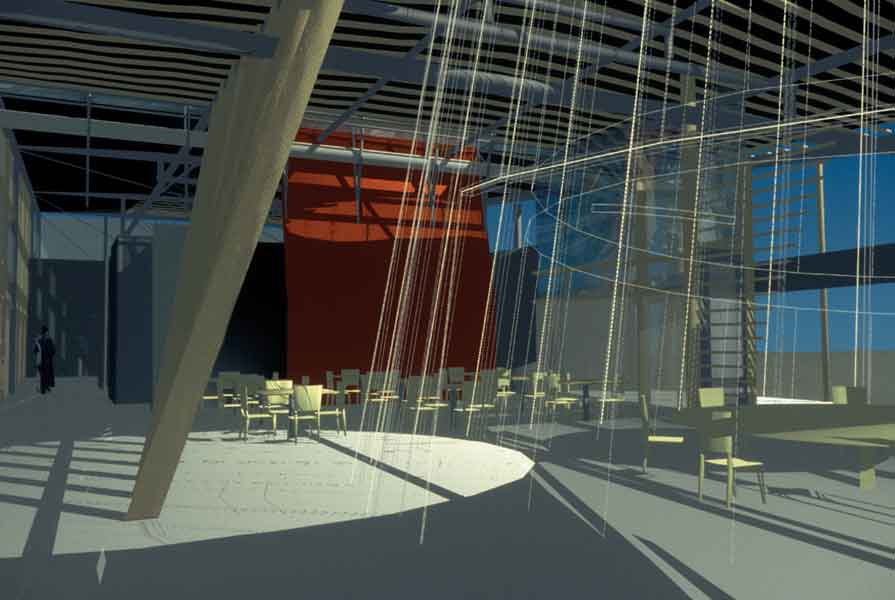

Xiyuan Monastery University, Suzhou, Roto Architecture.

Courtesy Michael Rotondi

What makes successful design? Is it having your projects published in different media outlets? Is it, as many design and architecture schools imply, an aggressive design aesthetic that you promote, along with your charisma? In speaking with three established architects regarding their own work, an unexpected theme revealed itself in how they have attained success. They listen.

Victoria Meyers, partner at Hanrahan Meyers Architects (hMa), observed in an interview on architecture education, “With clients, students will say, well, if you were just really tough, if you just put your foot down, then the clients will listen. And I tell them, no, I really can’t. There really is a budget. I really do have to do this. There really are realities that you have to deal with.”

Peer-reviewed studies show that listening is essential to producing the best outcomes, whether we are discussing a practice in law, medicine, or in this case, architecture. The studies identify different areas important to facilitating listening. One of these is educating the client. To architects and designers this may appear to be the easiest because they are used to providing important information, and explaining it. But this is not enough.

Chapel of the Light, hMa

Courtesy Hanrahan Meyers

Educating must be accompanied by a listening skill, two-way communication. This means using language the clients understand, not devolving into trade-speak that designers use to impress their colleagues, but actually convey very little. In addition, architects and designers need to respond to clients, rather than trying to “persuade” them to another viewpoint. This goes together with providing choices based on what clients’ needs are, as Meyers likes to say.

“When you start, you have limitations because you don’t have as much experience with all the materials, all the processes, how everything works, so you have compensate more with your design aesthetic, although that is also limited,” notes Peter van Assche, founder of Bureau SLA. “Over a few years, you are more able to put this aside and listen to really what is needed by the client. You act on that, which has less of [the designer] and more of what is needed. And surprisingly, it produces much more interesting projects.” For example, what may initially appear to be a design limitation, such as cost restraints, actually produced a far more creative solution regarding van Assche’s materials and program.

Buddhist Meditation Metta Vihara, Bureau SLA.

Courtesy Bureau SLA

Of course, there are many ways of listening. During an interview with Michael Rotondi of Roto Architecture on his work in sacred spaces, he noted that listening is an activity that engages him completely. “The first thing was to stop thinking about designing a signature architecture,” he said. “Instead I try to listen to whomever I’m working with and then try to jump over my own shadow when I’m designing.

“I love people. I love listening to their stories. You get a lot more information from people when you ask questions to listen and not turn everything into your own story. Like you listen and say oh, that reminds me of the time, and you’re off talking about yourself. If you really want to learn, that’s the last thing you want to do is talk about yourself. So when I was working with American Indians, the elders made it clear that I was there to listen to their stories and convert their stories into buildings.”

This, then, is the key. Listening to the client’s needs for such practical information as to how spaces will be used and cost limitations, to more abstract information such as philosophies and cultural narratives, are essential to shaping each of these architects’ work. One, particular style of listening is not more effective than another, but what repeatedly arises in each of their explanations is that they follow some of the basics of empathizing with others. The results? These projects expresses less the architect’s “style,” more the needs of their clients—in utterly unique ways.

Sherin Wing writes on social issues as well as topics in architecture, urbanism, and design. She is a frequent contributor to Archinect, Architect Magazine and other publications. She is also co-author of The Real Architect’s Handbook. She received her PhD from UCLA. Follow Sherin on Twitter at @SherinWing .