April 30, 2012

The Tiny Streets and Trinity Row Houses of Philadelphia

Some of America’s first urban workers lived in a unique type of Philadelphia home called a Trinity. Examples date from 1720. Trinities were built to house the artisan classes flocking to a burgeoning city; but while these workers moved on to populate America, the Trinity House didn’t follow them. But the Trinity and the narrow streets […]

Some of America’s first urban workers lived in a unique type of Philadelphia home called a Trinity. Examples date from 1720. Trinities were built to house the artisan classes flocking to a burgeoning city; but while these workers moved on to populate America, the Trinity House didn’t follow them. But the Trinity and the narrow streets that contain them warrant a closer look.

A Trinity, as the name suggests, consists of three rooms stacked on top of each other – and that makes the whole house. A Betsy Ross stair punches through, basically an elongated spiral stair that is so narrow and steep that, instead of a railing for balance, you haul yourself up using a vertically mounted steel bracket.

Trinities may have the kitchen in the basement, living/dining on the first floor, bedroom/bath on the second, and a loft room on the third floor. A “Betsy Ross” stair is diagramed on the right.

Like a typical row house, a Trinity sits on the front property line and comes with a small backyard. While all row houses consist of stacked floors, a Trinity is unique as each floor contains only one room that makes for a tiny footprint. Some find the Trinity’s petite stature charming and quaint, even adorable. Others find them claustrophobic, dark, and awkward. Most agree, though, that they are a cool historical relic.

Trinities cluster together on quaint little streets, just one cart wide with narrow sidewalks. At first glance, the streets appear to be alleys, but unlike alleys the tiny streets provide front door access to the houses that flank them. When you turn onto a Trinity Street, you leave the gritty, car honking city behind and enter fairytale land – quiet and tranquil, with a slight breeze rustling the leaves and sun sparkling on floating pollen; no cars and few pedestrians mar the peace. The sidewalks, wide enough for only one person, encourage pedestrians to spill off and claim the asphalt as their own. Neighbors sit on their stoops and share a drink or play horseshoes together.

A car can slowly squeeze between bollards down these single lane “streets”..

These tiny streets really work. Woven into the city grid, they create pedestrian zones without using forceful barriers or strident agendas. While too narrow for cars to move down comfortably, they don’t completely shun them. Here pedestrians and cars interact peaceably. Urban planners continue to propose blocking streets to automobiles. Philadelphia already tried this, when the city blocked a portion of Chestnut Street to cars for 20 years to great controversy and ultimate failure (businesses foundered). The beauty of Trinity Streets is that they don’t eliminate cars – they castrate them. They provide quiet pedestrian areas slammed against bustling urban zones. Quiet and Loud separated but near. Perfect.

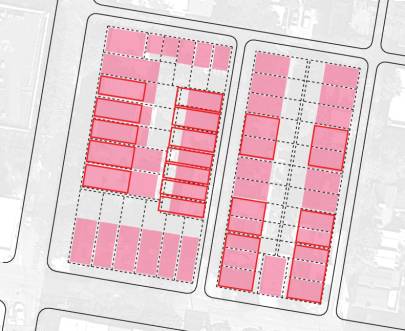

Single lane streets with houses fronting them shown in red, city grid through-streets shown black and named, other streets shown black. A quiet single lane street is located just a block from Broad Street, Philly’s six lane grand boulevard.

These funny single lane front-streets squeeze in between Philly’s hyper-rational east-west/north-south grid in a willy-nilly fashion, a result of early developers and homesteaders chopping land into blocks as-they-could to claim a piece of dirt for the teeming proletariat. This frenzied speculation resulted in overcrowding and sanitation problems at the time. But now non-through streets function like the suburban cul-de-sac to create a quiet defensible public zone. Unlike the suburban sprawl that spawned the cul-de-sac, these tiny streets subjugate the car and contribute to walkable sustainable city living. The tiny street deserves new life in modern urban planning.

Tiny streets needn’t access only tiny houses. The red boxes show possibilities for homes with larger foot prints on two city blocks.

Juliet Whelan owns Jibe Design, an award-winning firm creating architecture which weds profound design with environmentally responsible solutions.