March 28, 2014

How Do We Make Our Cities More Resilient? Make Them More Natural

How biomimetics could be the key to our urban future

Scientists predict that extreme meteorological events are becoming more frequent and destructive. For instance late last year, Typhoon Haiyan, the strongest storm recorded in the world so far, decimated central island cities in the Philippines. Recent data sourced from the Japanese Meteorological Agency indicated extreme weather occurrences across the globe. These pose critical challenges to our current and future rebuilding programs in cities where extreme weather has become the new “benchmark for disaster prevention,” as suggested during a congress meeting in the Philippines by the UN Champion for Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation for Asia Pacific, Senator Loren Legarda. What are the systems and strategies that can get us to resiliency?

In searching for sustainable strategies for the Leapfrog Project for Central Philippines rebuilding program, I came across the Global Innovation Science Handbook. The volume, compiled by the International Journal of Innovation Science, contains 50 chapters, each one of which tackles innovation within a variety of industries. The book’s ninth chapter, “Biomimetics: Learning from Life,” focuses on biomimetics and suggests ways that the built environment can learn from the natural world. The text, written by design scientist and futurist Melissa Sterry, grips you with insights on two great fields of human endeavor: leading-edge science and technology. While it has a sense of otherworldliness bordering on “[a] science fiction film set far in the future,” as Sterry describes, it’s delivered in an accessible prose that will be appreciated by practicing architects, designers, and even casual readers. The text provokes thought about biomimetics as the intuitive part of our natural self and environment.

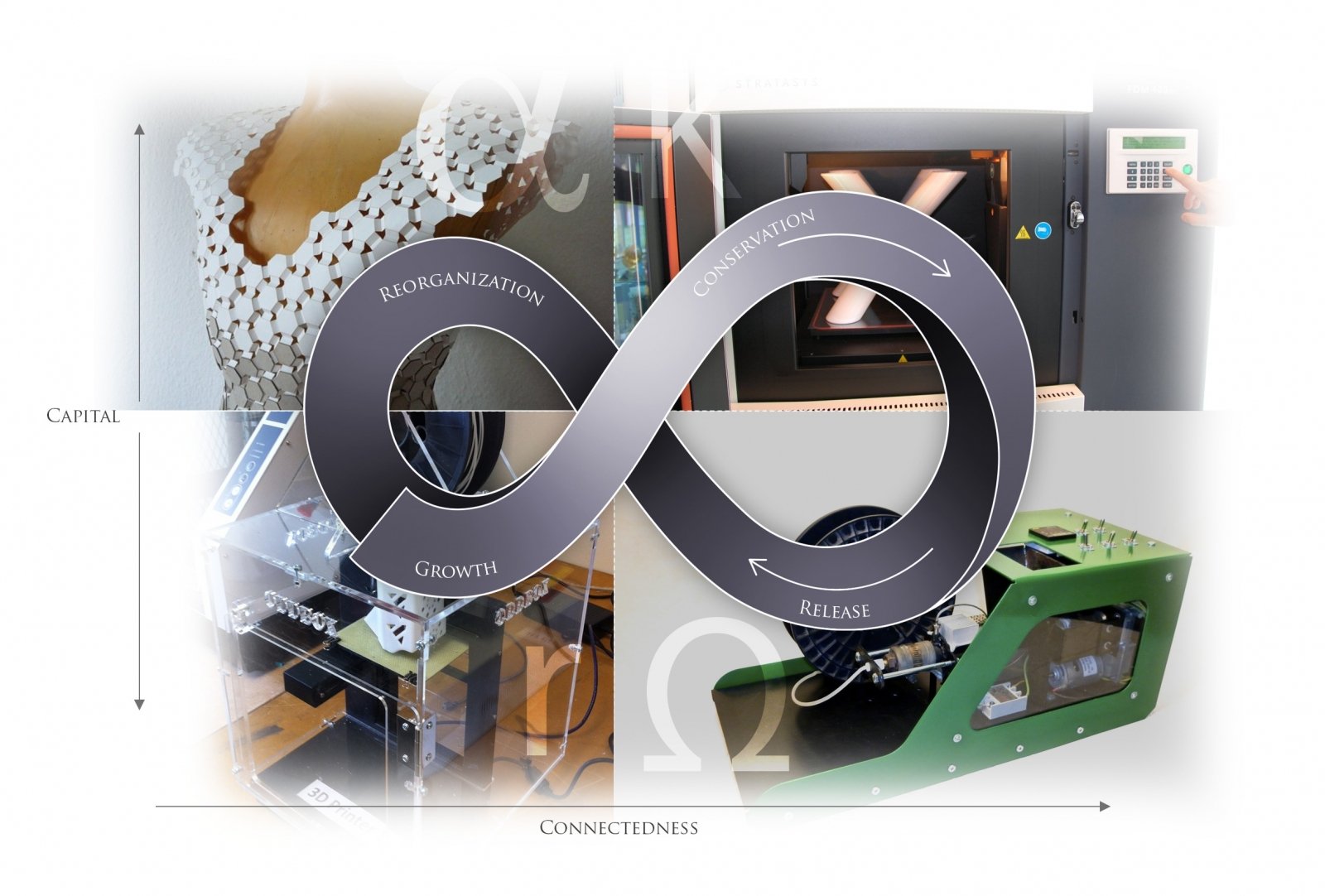

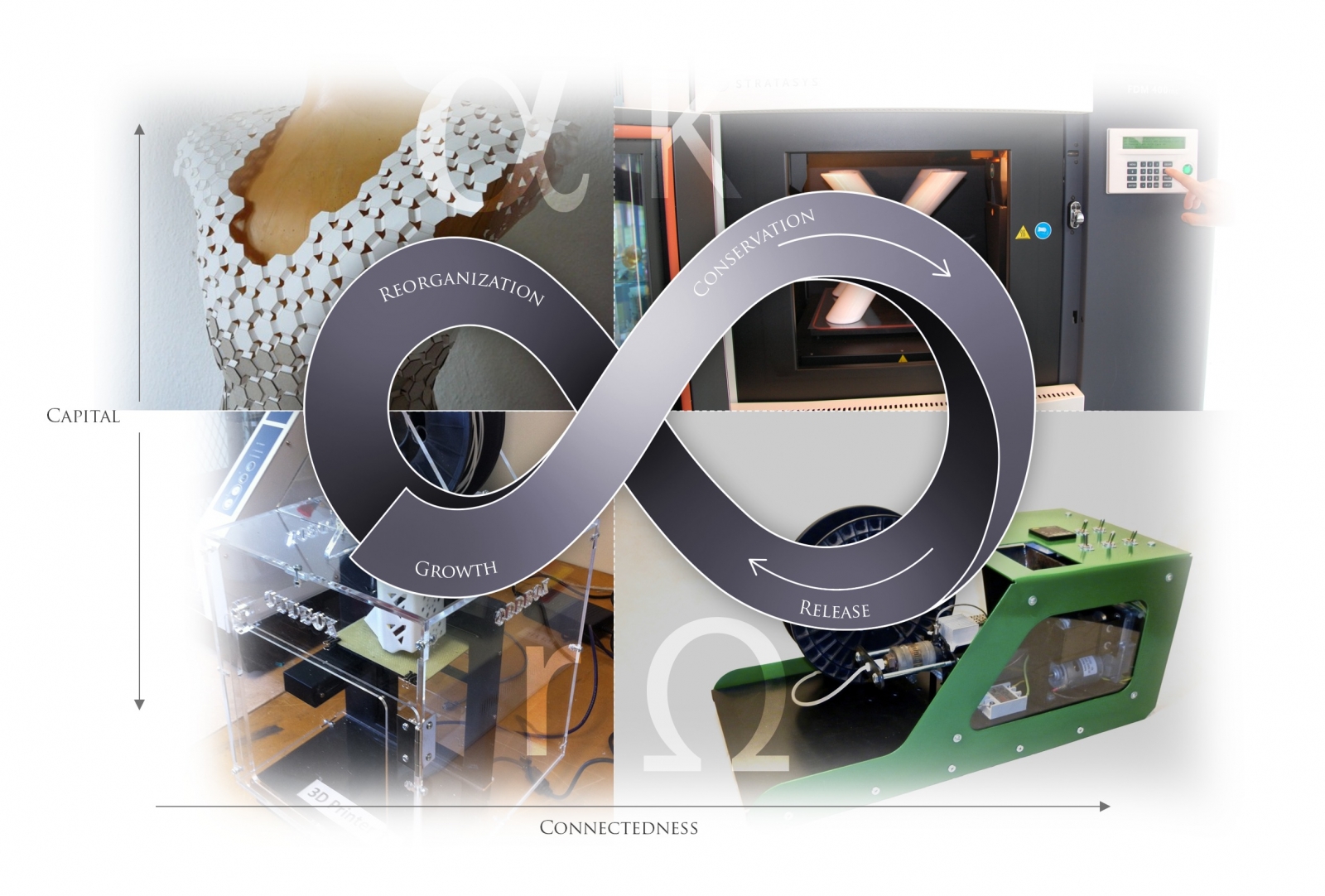

A model for “3-D printed Panarchy,” as outlined in Sterry’s text, which borrows the term from systems theory, particularly its emphasis on nature. When applied to a field of design, say 3-D printing, the model can be used to develop future economic and environmental lifecycles. In this case, innovation at the edges drives the development of a commercial 3-D printing market. Plastic recycling provides a continuous supply of materials, which are used to develop new product markets, such as 3-D printed goods.

The chapter is broken down into sub-topics that investigate the issue of bionic, from the scale of the human body to the city. “We All Have the Technology: DIY Bionics for All” suggests the creative potential of developing nations, where they are not limited by old methods of manufacturing and the lack of industrial-scale machines for production. “DIY Bionics” further expands on this point. Consider this: if one-third of the world’s population is online and 60 percent of these users are from developing countries (per a United Nations 2013 survey), then a maker economy will make it possible for them to flourish.

The topic that resonates with me as an architect is “A City for All Seasons: Biomimetics in the Built Environment.” It challenges us to confront our ability to suspend disbelief and at the same time inspire creativity for our own agency.

Perhaps one of Sterry’s strengths is her ability to bring to life the colorful creations illustrated in leading-edge science and technology. They become convincing potential drivers that intuit solutions to some of the world’s most pressing issues like the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goal No.8, which aims to develop global partnerships for development.

This handbook would be a meaningful resource and inspiration for rebuilding projects such as those in the Philippines affected by typhoon Haiyan. You can hear more about the Bionic City and from Melissa Sterry about Bionic City, including her sensitive observations about nature and a better world where everyone could flourish, in her upcoming pre-AIA National Convention lecture at the Apple Store theater in Chicago this June.

Lira Luis, AIA, RIBA, NCARB, CeM, LEED AP BD+C is a global architect specializing in organic architecture. She holds multiple architect licenses in Asia, North America, and a Chartered Architect designation in the UK. She is currently a Presidential-Appointee to the national leadership of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Diversity Council and the Advisory Group of the Practice Management Knowledge Community, as well as board director of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin Fellows.