July 31, 2017

Life in the Dying Urban Village: A Photographic Journey into Baishizhou

Less than forty years ago, Shenzhen was a small trading town of fewer than thirty thousand people. You can still find traces of its past in the twisted alleyways and crowded courtyards of Baishizhou.

Through these images I explore a people and a place. In time the barren concrete and twisting alleys of Baishizhou will be gone, and with them, the physical memory of one of Shenzhen’s last urban villages. Less than forty years ago, Shenzhen was a small trading town of fewer than thirty thousand. In Baishizhou you can still catch glimpses of that epoch, nuances of a steadier, calmer tempo. As the city expanded, Baishizhou remained, in many ways, as it was. That is not to say nothing changed. A spirit of survival and the strength of community maintains a steady stream of newcomers. What was initially a first stop on many migrants’ rural-to-urban journey, Baishizhou often transforms from a place to stay to a place to live. In turn, this drives a continuous evolution of physical landscape and social identity.

Surrounded by a combination of typical high-rise developments and patches of luxury townhouse-villa residences, some 150,000 residents find home in a dense, eclectic grid of aging apartment buildings. Hidden in its center is a set of collectivization-era row houses from the 1960’s (pictured in the title image), a reminder of the city’s humble origins. Streets are barely wide enough for two-way traffic, and automobile-motorcycle-oxen jams occur daily. Interning in nearby Overseas Chinese Town, I rented a room in an eight person coliving apartment here. As I wandered the labyrinth of streets and conversed with locals, I was immersed in a palpable social narrative, one that is inextricably connected with movement: the flowing of bodies, the passing of time, and the erosion of structure, both physical and invisible.

To live in Baishizhou is to live in an endless construction project, perpetually reverting back to the demolition phase. The physical remnants of these cycles are the patches of concrete forest, full of bare columns crowned with rebar leaves. Children dart through the grid, mothers hang clothes, and the typically masculine construction space takes on an impromptu domesticity. Scavengers hunting for scrap metal in discarded appliances and pieces of old buildings create an erratic metronome with the clanging of their shovels.

With cheap housing, light industry jobs, and abundant nightlife amenities, Baishizhou addresses many of the immediate needs of young people new to the city. As they resettled from all across China, diverse, authentic street food vendors have flourished, establishing Baishizhou as a gastronomic hotspot. Lamb skewers from Xinjiang, crayfish from Shanghai, pork belly buns from Xi’an – a moderately priced culinary smorgasbord around every corner means all demographics from sweatshop worker to white-collar techie has reason to visit. Small freight trucks carrying bok choy and watercress trickle into the neighborhood from nearby provinces as early as six in the morning, supplying vegetable stalls and congee shops with fresh produce in time for the morning commute. Later in the afternoon, live seafood arrives from coastal villages. The sight, sounds, and smell of the market combine with the constant movement of human and animal bodies.

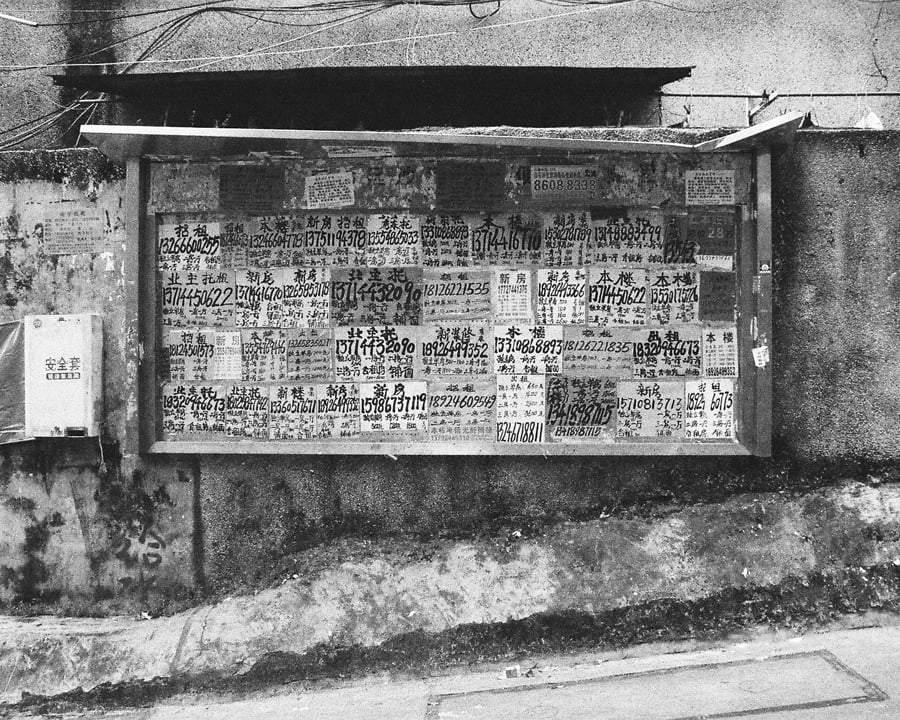

The organization is chaotic yet efficient; there is just enough space for everyone. Leisure, professional, and domestic activities mix closely, occasionally to comic effect: I once saw a young boy chasing a rooster a few feet away from a dentist pulling out a patient’s tooth—he had moved outside because his lights broke. Stalls, benches, signage, and businesses multiply and spread, forming a viral fluid that seeks to fill every gap in the cracked concrete. Every empty façade is a billboard, every horizontal surface an opportunity.

Composed of everything from structural contractors and sewage system repair, to rodent exterminators and ad-hoc Internet installation, a diligent network of laborers generates a large community workforce, many parts of which operate unregistered. Legality, or the apathy towards it, is a key determinant of Baishizhou’s popularity as a leisure district. My housemate Liu, an avid gambler and owner of a small women’s dress factory north of Baishizhou, tells me that millions of RMB change hands every hour in the hundreds of private mahjong dens. Unadvertised operations, hidden by the cobweb urban fabric and visible only to those who know they exist, are reminiscent of Hong Kong’s Kowloon Walled City, which would be less than an hour’s drive away if it still existed today.

As someone new to the city, I expected to be treated as an outsider, to be engaged with a casual wariness if nothing else. The reality was that few people asked, or cared, where I was from. When everyone is a migrant differences can be abundant, yet conversations I had generally focused on similarities. As migration discourse becomes increasingly divisive in the West, I have come to appreciate this openness even more. In a city fixated on modernity and growth, few consolations will be given to the labourers that made the city’s modernization and expansion possible. Likewise, little remorse will be given to the dirty streets, with their hotpot carts and plastic stools, despite their decades of accommodation. Caught between the city’s administrative center and its future central business district, Shenzhen’s largest urban village has been speculated on for decades, the subject of countless designs, analyses, and researches. Shenzhen’s seemingly limitless increase in property value and the demolition of industrial buildings to the north of Baishizhou, where many migrants find work, are signs that the inevitable is finally in motion. After the rubble is swept, the locals will leave too. To be sure – if they can afford it – some will have the privilege to enjoy the wider avenues, the cleaner sidewalks, and high-rises that are coming. Top-down planning and mass redevelopment, however, are not what typically lead to a resilient communal identity and a sense of belonging. Perhaps Baishizhou, from market town to affordable density, has always been about coming and going, and this next transformation is but a step in its own migratory journey. Temporality, however, makes what will be lost no less valuable to me.

Frank Wang is an architecture student at Cornell University.

If you liked this post, then check out “A Photographic Tour of Taliesin West Today.”