October 19, 2015

Play is for Everyone: Making NYC Playgrounds More Equitable

New York City parks and recreation centers lack integration across gender, age, race, and socio-economic demographics.

Children at play in Heckscher Playground, New York City.

Photo Credit: Mathews Nielsen

The following is part II of this two-part series on the expanding definition of what it means to be a playground in New York City. Our previous post looked at the state of progressive play in the city. This post examines boundaries to equity for play and recreation.

The word “equity” has permeated through all levels and areas of New York City’s agenda with the current mayoral administration. Earlier in October, the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation identified 67 parks that received little or no investment in the last 20 years and placed them on an accelerated design schedule to service low-income neighborhoods. However, equal distribution and access to play and recreation is not solely addressed by income level. To truly make spaces that are accessible to all New Yorkers, we need to diminish other barriers to play, both physical and social.

Physical barriers are the most obvious ones to dissolve. At a recent talk, NYCDPR Commissioner Mitchell Silver introduced the idea of “play without borders”—that whenever possible, the hard line between playgrounds and their surrounding neighborhoods should be dissolved. His presentation highlighted images of the tall chain link and iron fences separating playgrounds from the city sidewalk and parkgoers from plantings, an unfortunate legacy of the crime-ridden New York of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Integration into a larger context, whether urban or natural, creates opportunities for richer interactions with neighbors, friends, and other parkgoers. Blurring the boundaries between play space and the world beyond also expands room for play and recreation.

Central Park’s Heckscher Playground, originally built in 1926 and redesigned by Richard Dattner in 1969, features a playground built directly into the side of a large rock outcropping known as Umpire Rock. Recent modifications have kept the overall design of its concrete structures while updating them to meet current playground guidelines. Play equipment dovetails neatly into natural formations and increases the vertical scale of the playground, creating areas that challenge a wide age range of children, as well as providing areas for caretakers and others to sit and relax.

New York’s neighborhood parks and playgrounds have also struggled with how to balance active and more passive forms of recreation, thereby affecting the diversity of users they attract. When we think of recreation or play in the city, play courts of all varieties, ball fields, and play equipment come to mind instantly. These amenities require large, defined spaces that generally can only be fulfilled communally, and are therefore a known commodity in programming public recreational spaces. Attempts to incorporate passive recreation tend to become more of an afterthought once budget and space constraints come into play but these passive recreation centers are highly valuable in attracting a more diverse group of users to public spaces.

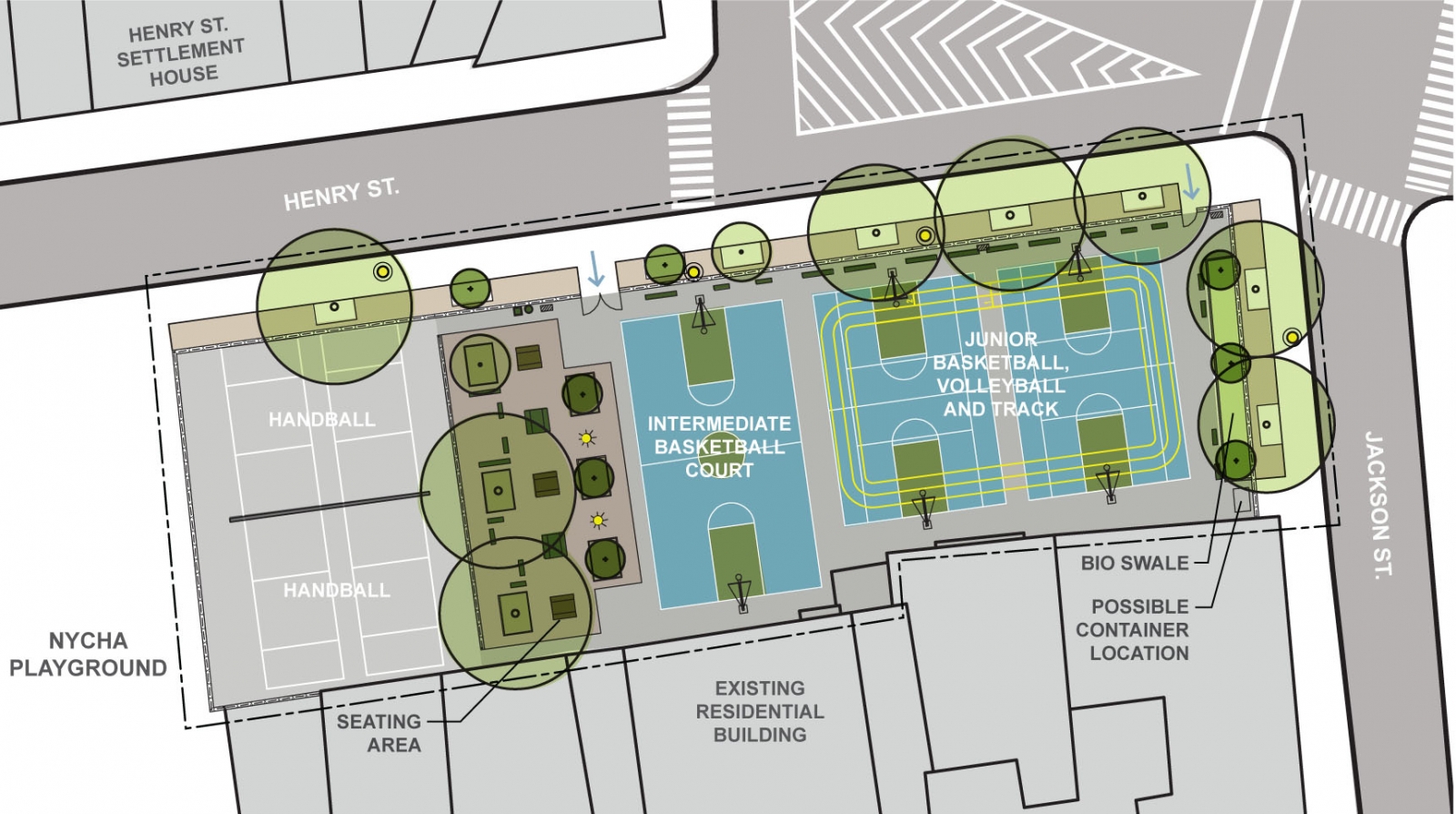

Social interactions and the activities they surround fall largely along gender and age lines, with traditional playground layouts attracting a young, mostly male population. Missing from this demographic are the categories of females as they outgrow childhood playgrounds, working adults who find that private indoor gyms better answer their needs, and seniors looking for space to gather and socialize. The program elements at Henry M. Jackson Playground now incorporate volleyball, a track, and more seating to replace and augment existing basketball courts in the hopes that these activities will attract more females, as well as a wider age range of users. Adding outdoor fitness equipment for adults and seniors has also been wildly successful in other neighborhood parks.

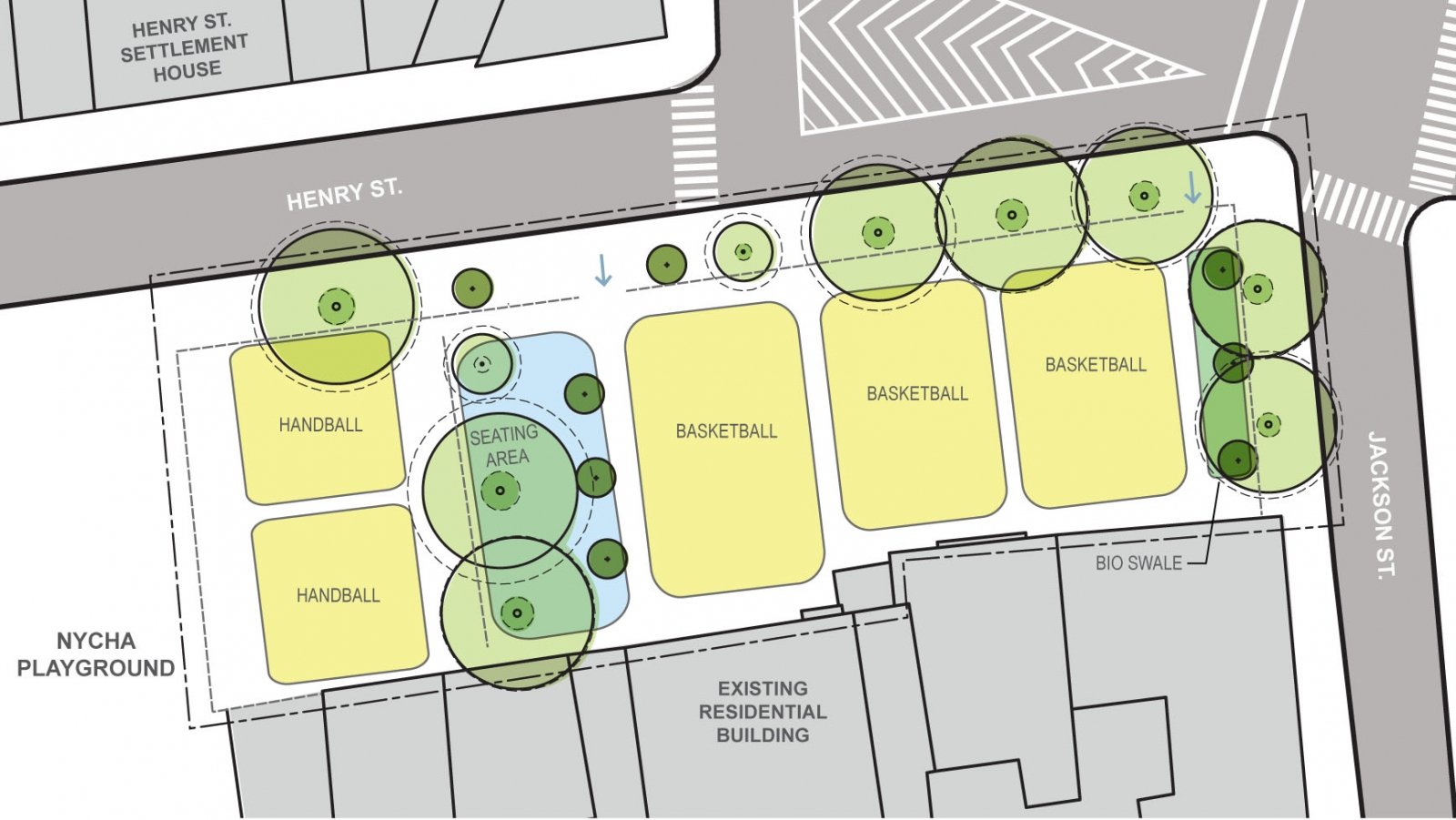

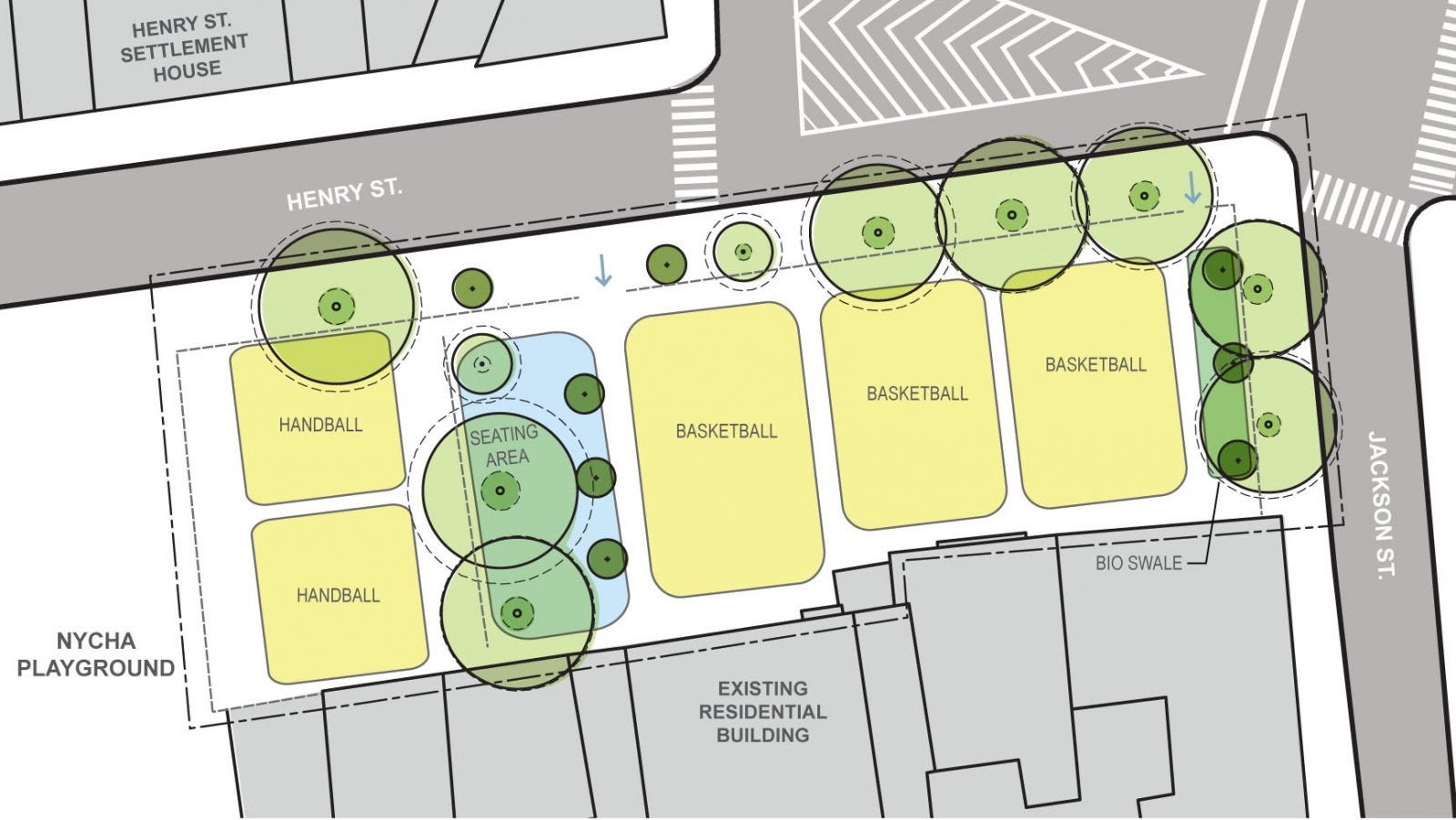

The layout of the existing Henry M. Jackson Playground on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

Photo Credit: Mathews Nielsen

The new programming for the Henry M. Jackson Playground is designed to attract diverse users.

Photo Credit: Mathews Nielsen

User diversity, however, does not equate to the equally important need for social integration.

In larger parks, there may be a place for everyone who chooses to partake, but areas for people to intermingle and socialize are few and far between. Well-intentioned signage banning everything from skateboards and scooters to adults in play areas is one symptom of a more subtle form of exclusion and can set the tone for making spaces feel less attractive and welcoming. Armrests dot benches in public spaces to discourage people who have no better options from sleeping on them. Parkgoers take their cues from their surroundings. Pushing equity and inclusiveness can only go so far if we have already limited the populations we are interested in including.

One successful area of integration can be seen in skateparks, host to an often maligned demographic. Though heavily male dominated, they are very multigenerational, with older and younger skaters of diverse cultural and social backgrounds intermingling and exchanging tips and encouragement. Chess tables in public spaces also tend to draw a particularly diverse crowd of strangers to participate, watch, and even openly critique. Making play and recreational spaces more generationally and socially integrated makes for stronger community ties and bonds, and ultimately a better New York.

A chess game in progress at Washington Square Park.

Photo Credit Flickr

Being a large, densely populated city is both an advantage and disadvantage when it comes to adapting to a rapidly evolving understanding of play and recreation in everyday lives. The breadth of public parks makes the process of adapting existing regulations to our newer understanding a slow one. Even slower is the realization of it expressed in the built environment. On the other hand, the network of parks and play spaces is large enough that not everything needs to be for everyone all the time; new initiatives and more diverse programs can be spread out to serve a broad spectrum of city residents in a neighborhood.

Removing barriers to recreation and adding more progressive forms of play spaces that blur the boundaries between playground and the city creates possibilities for public space and uses that may have been previously overlooked. In a city with a rapidly expanding population, no opportunity to maximize space should be overlooked.

Grace Lo, RLA, ASLA, LEED AP is a full-time landscape architect at Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects, a part-time yoga teacher, and an aspiring plant nerd. A born and bred New Yorker, she has nine years of experience working on public, commercial, and residential projects throughout the New York area and has a passion for involvement in urban revitalization in all shapes and forms. She received her BSLA from Cornell University.

This is one in a series of Metropolis blogs written by members of Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects’ Green Team, which focuses on research as the groundswell of effective landscape design and implementation. Addressing the design challenges the Green Team encounters and how it resolves them, the series shares the team’s research in response to project constraints and questions that emerge, revealing their solutions. Along the way, the team also shares its knowledge about plants, geography, stormwater, sustainability, materials, and more.

Follow Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects on Twitter at @mathewsnielsen and Instagram at mathewsnielsen.