April 27, 2015

The Metropolis Guide to Mexico City’s Design Landscape

With their feet planted in their heritage, ears open to international trends, and eyes firmly set upon the future, the city’s designers and architects are poised for the spotlight.

The neighborhood of La Merced, Mexico City’s historic center, once contained the splendid temple of Nuestra Señora de la Merced. After the construction of new markets, all that remains of the temple is the cloister and arcades. But Talavera Street still floods with the devout every January, bringing out the vendors (with effigies of baby Jesus), as well as the craftspeople, who make clothing for figurines, decorations, and other accessories.

Courtesy Miscelánea

At 8:30 on a chilly Friday morning last October, a long, winding queue had formed outside Mexico City’s Tamayo Museum.

Mostly young, local designers, they had gathered for the conference program of Design Week Mexico, seemingly unfazed that the first international speaker wasn’t due to start for another hour and a half.

“You go to some of these huge international platforms in other countries, and there are 30 people in the lecture rooms. We had 2,800 people going to the lectures here on Friday,” says Emilio Cabrero, an architect and the director of the design week, now in its seventh year. “It’s part of the agenda to bring in people from other parts of the world to share their experience.” The week’s events—special exhibitions and urban interventions, opportunities for young talents, and events at showrooms—are planned to slake the thirst for international exposure in one of the world’s biggest metropolises.

There couldn’t be a better time for Mexican talents to claim their spot in the limelight, as the world’s eyes are on Latin America as a source of ideas. Major exhibitions on architecture and design from the region have opened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Museum of Arts and Design, and Paris’s Maison&Objet fair last January included a showcase of emerging Mexican designers. The Audi Urban Future award in 2014 went to Gabriella Gomez-Mont, Jose Castillo, and Carlos Gershenson, for a scheme to disentangle Mexico City’s infamous traffic jams.

Much of this attention has to do with the confidence one senses in young creative people in Mexico City, an ability to synthesize their rich culture into something new. “Even if we don’t want to burden ourselves with this typical image of traditional crafts,” Cabrero says, “the contemporary approach builds upon it in many ways.” A renewed pride in their history also helps—forebears like Luis Barragán and Pedro Ramírez Vázquez remain touch points. A generation of designers and architects is working with the proud conviction that theirs was a great design city, and will be once again.

The Metropolis Guide to Mexico City’s Design Landscape

Centro Histórico (El Centro)

Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura

Building Identity: Architects to Watch

Movers and Shakers: C Cúbica Arquitectos

Crafty Innovators: Rising Design Stars

Humanizing the Legend: Pedro Ramírez Vázquez

The City’s Creative Heart: Centro Histórico

Walking the winding halls of Mercado de Sonora, one might mistake Don Antonio Espinoza’s stall for an altar. But La Michoacana is actually a one-stop shop for a variety of traditional objects from all over Mexico, including dance costumes, toys, and the fantastic wooden animals called alebrijes.

Courtesy Miscelánea

The Plaza de Santo Domingo is ringed with ornate eighteenth-century edifices, but it’s also where a row of printers set up shop every day, some with small presses in their little wooden kiosks. You can come in the morning with an idea for business cards or a party invite, and have it designed and printed by the afternoon. A few blocks away, just a short walk from the imposing Supreme Court building, you can bring a jacket to the Pasaje Balvanera, and either have a ready-made sequined image appliquéd on it, or leave it behind for custom embroidery.

Many old, gracious cities have neighborhoods like this, where tourists come to gawk at landmarks while the locals run a bustling creative economy. Mexico City’s historic hub—known locally as Centro Histórico, or simply El Centro—has an extraordinarily high concentration of makers and entrepreneurs, some of whom have been operating in the area for decades.

Spread over an area of 6.2 miles, El Centro was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1987. To help the crush of customers and businesspeople who descend on the neighborhood, the enlightened authorities gave the area its own public-transit system. Picking up paper supplies on Las Cruces and then heading all the way to Eje Central Lázaro Cárdenas is now as easy as hopping on a tram or two.

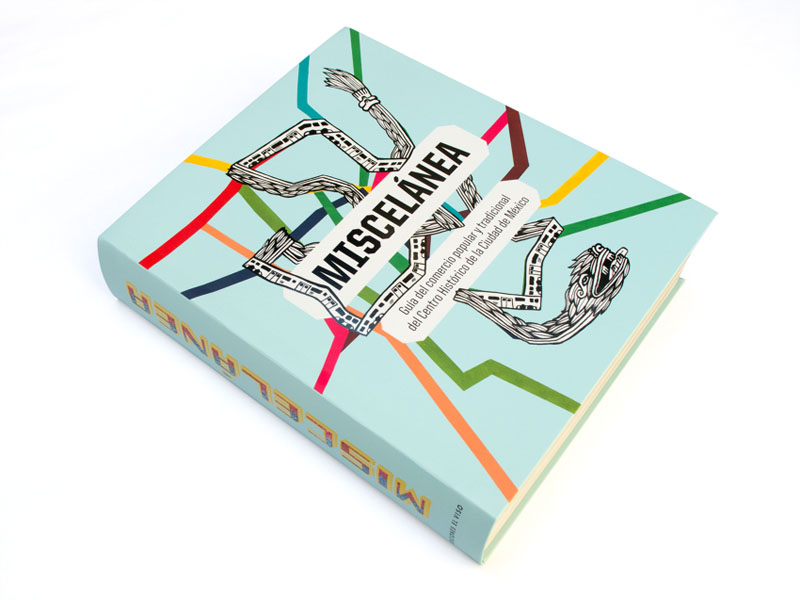

Miscelánea, a guide to El Centro’s businesses.

“This market is huge, but in a way it’s more fluid,” Antonio Calera-Grobet writes in the recently published book Miscelánea (Ediciones El Viso, 2013). “It unfolds in small doses. It’s a secret between small-business owners and dealers: Move slowly until you move the mountain, stubbornly.” Edited by Marie-Aimée de Montalembert, and flooded with images of life in El Centro, the 766-page volume is an invaluable guide to thousands of businesses and marketplaces. The fact that the book is in Spanish should prove no barrier to the intrepid explorer—clear maps and an exhaustive color-coding system mean that the guide can be easily unlocked with an occasional glance at Google Translate. In any case, many local designers insist that no other comparable record of the city’s traditional creative node exists, so it’s worthwhile for non-Spanish speakers to persevere. A visit to El Centro will reward them with rare insight into what drives Mexico City’s enormously diverse visual and material culture.

A Home for History: Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura

The Archivo is housed in a Modernist home designed by Arturo Chavéz Paz in 1952, with a garden that closely resembles the one at the Casa Estudio Luis Barragán next door. Founder Fernando Romero took over the building as his studio in 1992, and moved his collection here in 2012.

Courtesy Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura

General Francisco Ramirez, a very small street, is one of Mexico City’s gems of architecture and design, although you’d never know from looking at it for the first time. High compound walls guard Casa Ortega—which the Pritzker Prize–winning architect Luis Barragán designed in 1943—and Casa Estudio Luis Barragán, the architect’s own home, which is now preserved as a museum. In 2012, they were joined by a third design treasure, also tucked away from sight. A brown steel sliding door and a grotto-like passageway lead to the lush garden and Modernist glass facade of the Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura, a young cultural hub that stands shoulder-to-shoulder with its illustrious neighbors.

“In cities like London or New York, there are many places where you can go see Modern design classics,” says Regina Pozo, director of the Archivo. “But designers in Mexico City never had such a space.” The architect Fernando Romero, known for de- signing the futuristic Museo Soumaya and slated to design the city’s new airport, set out to fill this gap. Romero and his wife Soumaya Slim had amassed 2,800 international and Mexican design objects—a motley mix that valued a chair by the French Modernist Jean Prouvé as much as a rooster-shaped egg basket from Mexico. After spending four years incubating the project, and appoint- ing the art historian Pozo as director, Romero purchased the property adjacent to Barragán’s home to house the archive.

The combination of idiosyncratic objects, a beautiful location, and a director who came from outside the design community paid off—the inaugural exhibition, Happiness Is a Hot (and Cool) Sponge, pitted functional classics like Converse All Star shoes against poetic masterpieces like a glass slipper by Maison Martin Margiela. The Archivo also started a competition for emerging architects—the young firm Pedro & Juana was the first chosen to create a temporary pavilion for Archivo in 2012. Last year’s exhibition, Copies. Transformation and Development in the Creative Processes, took a provocatively neutral stand on vernacular versions of design classics. The first show at the Archivo this year focuses on bicycles. Mexico City has a big biking culture —drop-off stands for rented bikes are visible all over the enormous Chapultepec Park. Since May 2007, local authorities close off the arterial road of Paseo de la Reforma on Sunday mornings to give cyclists free rein. “The city is promoting biking in this hipster sort of way, while there are so many neighborhoods in Mexico City where bicycles are essential to people’s livelihoods,” Pozo says. “This exhibition will be our way of connecting better with the city and its people.”

Building Identity: Architects to Watch

The Casa Arenas by Estudio Macías Peredo

Courtesy Jaime Navarro

The Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura is a keen supporter of up-and-coming professionals—the institution runs an occasional pavilion contest for young architects. Here, Regina Pozo, director of the Archivo, handpicks emerging architectural talents from her city.

1. Estudio Macías Peredo

In 2014, Salvador Macías Corona and Magui Peredo Arenas were recognized by the Emerging Voices program of the Architectural League of New York both for their designs and their historical research. The pair practice out of Guadalajara, but have ongoing projects in Mexico City.

2. Productora

Founded by four architects of different national origins, Productora has already earned an impressive international presence, building in places as far apart as Caracas, Venezuela, and Inner Mongolia, China. They were awarded in the 2013 Emerging Voices program by the Architectural League of New York.

Alessandro Arienzo’s exhibition design for Happiness Is a Hot (and Cool) Sponge at the Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura.

Courtesy Alessandro Arienzo

3. Pedro & Juana

Mexican Ana Paula Ruiz Galindo and German Mecky Reuss both studied at Sci-Arc in Los Angeles before establishing their whimsical, craft-inflected practice. “They have proven consistent working for important clients such as Jumex Museum and ourselves,” Pozo says.

4. Alessandro Arienzo

A graduate of the Universidad Iberoamericana who returned to practice in Mexico after two years in Europe and Brazil, Arienzo is not only an architect, but is also engaged in plastic arts, editorial projects, and tattooing. “He is a true aesthete,” Pozo says.

5. Zeller & Moye

Based in both Mexico City and Berlin, Christoph Zeller and Ingrid Moye are currently building a studio for the artist Pedro Reyes. Alumni of SANAA and Herzog & de Meuron, they are “soon to be profiled in the global arena,” Pozo predicts.

Movers and Shakers: C Cúbica Arquitectos

As part of Design Week Mexico 2014, various architects were each assigned a room in a showcase home; C Cúbica experimented with color-changing ambient lighting.

Courtesy Alfonso Béjar

Most people who attend Design Week Mexico—with all its programming, partnerships, and events—might be surprised to learn that it is the brainchild of four architects who also run full-fledged practices. In 2009, Emilio Cabrero, Marco Coello, and Andrea Cesarman of the 25-year-old firm C Cúbica Arquitectos partnered with the architect Jaime Hernández to create and organize the annual event. Simultaneously, the firm designs beautiful residences and institutional buildings, while successfully running two retail outlets, and curating exhibitions on architecture history.

“We are all a bit crazy,” admits Cabrero, who first founded the furniture store Artelinea in 2004, and then joined with Hernández to launch the design store Blend in 2010. The 37,674-square-foot space in the Polanco neighborhood sells a mix of international products. “The concept is really to blend,” Cabrero explains. “Ultimately in people’s homes, they don’t have products by just one brand, they always have a little bit of everything—different techniques, different objects.” Blend also sells produce via its rooftop market, has a café supervised by star chef Enrique Olvera, and stocks an enviable collection of design publications in its bookshop. The large windows, visible to all on the main thoroughfare of Paseo de Las Palmas, also act as a showcase for Design Week Mexico every year.

Objects from around the world fill the Blend concept store. In the foreground are a metal mesh armchair from Design Workshop, a coffee table from the Belgian firm Heerenhuis Manufactuur, and side tables from the Dutch company Pols Potten.

Courtesy René Enríquez

Coello is the curator of the group. During Design Week in 2013, he put together an exhibition on the legendary architect Luis Barragán, while last year he delved into the career of Pedro Ramirez Vázquez. “They are very different architects—Barragán is more intellectual and poetic, and Vázquez is more social and political,” Coello says. “Exploring the work of these people makes me think about how we can envision our own practice. I am designing buildings in districts like Oaxaca, which are some of the richest areas culturally, but are also very poor economically. So Barragán’s work makes me think about what a heavy burden, but also an amazing opportunity, I have.”

Much of what C Cúbica does is about building partnerships—with cultural institutions and local museums like the Casa Luis Barragán, with city officials, and with Maison&Objet in Paris and WantedDesign in New York. “All these interactions are very rich for us—they bring a deep value to the platform of Design Week in building a community at different levels,” Cabrero says. “Each year, we look at each other and wonder how we manage to do all of this.” Then they start all over again for the next year.

Crafty Innovators: Rising Design Stars

Déjate Querer’s felt Aldama rug is inspired by textiles from the town of Magdalena Aldama in the highlands of Chiapas.

Courtesy Déjate Querer

Part of Design Week Mexico’s agenda is to promote young talent—a mission that cofounder Emilio Cabrero is especially passionate about. Here, he names five designers from Mexico City to watch.

1. Foam

This design brand, specializing in edgy, precisely manufactured furniture, is the brainchild of Alejandro Grande and Omar Ramos. The duo is also undertaking interior projects, including one at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

2. Rococo

Starting out as a furniture-restoration business, Rococo has developed its own over- the-top design style, blending eighteenth-century flair with fair-trade artistry in a show- room in the Juárez neighborhood.

The Repisa shelf, from the first collection of products designed by Foam.

Courtesy Foam

3. Panorámica

A collective of six emerging designers who found that they shared core ethical concerns, Panorámica produces sophisticated products that employ materials in surprising ways—a case in point is the Colored Basalt collection, which imbues the stone with subtle hues.

4. David Pompa

The industrial designer’s products draw upon the skills of Mexican artisans, with whom he has been collaborating since 2009. He runs a store and a studio in Mexico City, and an office in Austria.

5. Déjate Querer

Industrial designer Ana Paula Alatriste and social anthropologist Rocío Cortés joined in 2011 to create three-dimensional rugs and wall hangings from pieces of felt, drawing inspiration from local colors and natural features.

Humanizing the Legend: Pedro Ramírez Vázquez

A view of the exhibition at the Museo de Arte Moderno, which focuses on the mutidisciplinary nature of Pedro Ramírez Vázquez’s work. The show includes some of his drawings and sketches, culled by the curator and Vázquez’s son Javier. Also on display is the large body of graphic and textile design work produced by Vázquez’s office, or under his supervision (above).

Courtesy Museum of Modern art, Mexico City & Design Week Mexico

Standing under the gargantuan concrete canopy of Mexico City’s National Anthropology Museum, it’s easy to see why this is the sort of thing the architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez came to be known for. Few other architects have wielded such influence over a city they didn’t themselves plan. An outsize figure who passed away in April 2013 at the age of 94, Vázquez designed many of the capital’s most beloved landmarks, including the Azteca soccer stadium, the Legislative Palace, and the Basilica of Guadalupe. He also had deep political connections, and contentiously led the organizing committee of the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City.

“He is one of the most prolific architects in the history of Mexico,” says Marco Coello, who curated a retrospective of Vázquez’s work at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. Coello sought to look a little beyond the legend for the show: “He designed and built the largest number of schools in Mexican history, for example. He was very concerned with social architecture, when it wasn’t so much in fashion.”

The exhibition, Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, Inédito y Funcional, also marks the 50th anniversary of the museum building, which Vázquez designed. It is a uniquely comprehensive look at the interdisciplinary outpourings of the architect’s office, from furniture to structural systems to graphic design (Vázquez had a hand in the iconic identity of the 1968 Olympics, with its pulsating lines). Indeed, there seems to be few aspects of design that Vázquez didn’t have a hand in. Working with the architect’s son, Coello has uncovered seldom-seen works, in sketches and plans. A particular gem is his unbuilt scheme for a giant fountain in the courtyard of the Louvre in Paris, where he was a consultant.

An authoritarian and a relentless international promoter of his country, Vázquez was a divisive figure in his lifetime, and remains so in most architectural circles. But Coello says his work is finding resonance with young professionals. “His architecture was in line with the Modern style, but he managed to give it a Mexican touch, in the materials and references to pre-Hispanic buildings,” he says. “He had a vision of a very contemporary Mexico.”