March 24, 2014

Kon Wajiro, Documenting Life in the Aftermath of Disaster

A current exhibition at the New School explores the diagrammatic drawings of the celebrated Japanese architect-designer.

Small sketches show fledgling barracks, tents pulled together around a tree trunk, a hunched figure lighting a fire nearby. Elsewhere, an illustration of a woman’s figure is littered with objects and text indicating “what she needs,” while a complementary sketch of a man depicts all the “things he wants.” Further down, a notated map diagrams the suicide points in Tokyo’s Inokashira park. These drawings and photographs are reproductions of originals that date back to 1923, done right after the devastating earthquake in the Japanese capital and carried on for years after. They also form the basis of an ongoing exhibition at the Aronson Gallery in the New School in New York City.

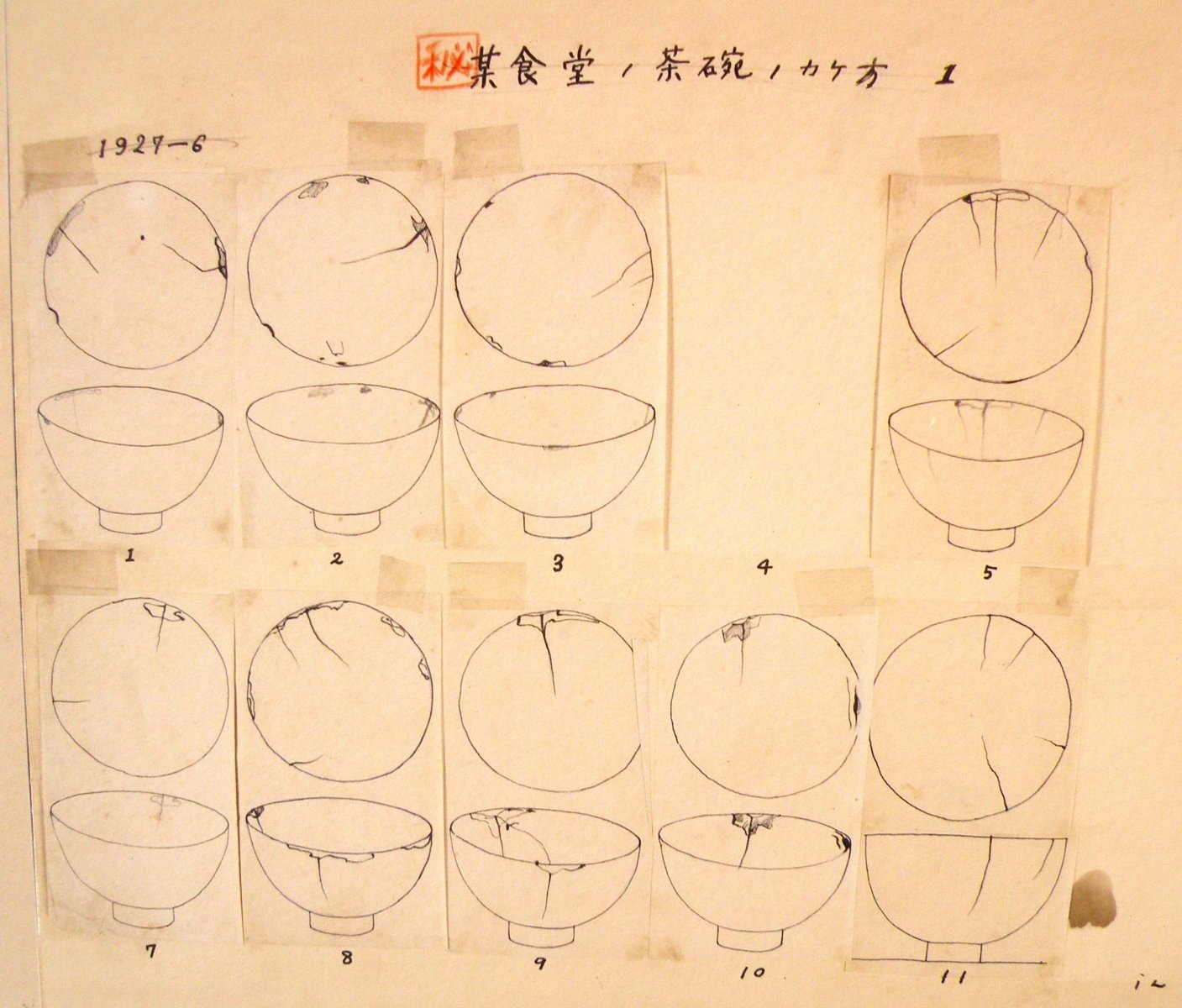

Design and Disaster: Kon Wajiro’s Modernologio highlights the architect/designer’s sketches and photographs, which capture moments of life in the aftermath of a natural disaster. On the one hand, the documents are simple snapshots of post-earthquake Tokyo that peer into the meager domestic spaces of the affected population. The focus, however, is often on the worn materiality of everyday life, rather than the makeshift structures or architecture proper. Kon’s implicit idea was that the “designed” space says little about those who live there; it’s objects—slippers, trash, utensils, chipped bowls, tools are strewn across these sketches—instead, that are more telling of people’s economic and cultural life.

Cracks on a bowl at a cafe, 1927, Kon Wajiro and Shozo Ozawa

Kon (1888-1973) studied design in Japan and worked closely with ethnographers, designers and artists. He is known as the founder of Modernologio, a school of thought that involved the documentation of modern life in Tokyo as it rapidly developed into a metropolis in the early Showa period (1926-1989). In the months after the earthquake, Kon along with his students visited the areas where earthquake-refugees tended to congregate. Depicting a society that had been flattened by natural disaster, and in a temporary period of reconstruction, these sketches show the act of living in its most fundamental state, stripped off any excess. “The day after the earthquake, people who had lost their homes began salvaging timber spared by the flames to use as posts and beams for simple new dwellings. Kon, with camera, pencil and notebook in hand, wandered through the ruins, recording his observations of temporary shelter as well as the new places of business that began to appear in ramshackle structures,” explains the exhibition’s catalogue.

Kon’s work bridges the distance between dense academic ethnography and its significance in practice as a design-based method of recording material change. Curated by Jilly Traganou of the New School and Kuroishi Izumi from Aoyama Gakuin University, Tokyo, both educators were attracted as much to the pedagagical significance of Wajiro’s sketches, as to their aesthetic appeal. “I was first drawn by his visual language; the fact that he paid attention to the quotidian and people’s material practices of everyday life. This was refreshing at a time when architecture and design education was focusing so much on the designer’s grand vision, rather than the inhabitants or users’ practices in relation to the designed artifact or space,” says Traganou. Kon was sensitive to the distinction between how spaces are designed and how they are actually used—the conceived space and the lived space. He wrote in 1924, “These black, red and blue houses with their roofs—sometimes light, sometimes heavy but often peculiar—are quite remarkable. Architects should take note of people’s ingenuity.”

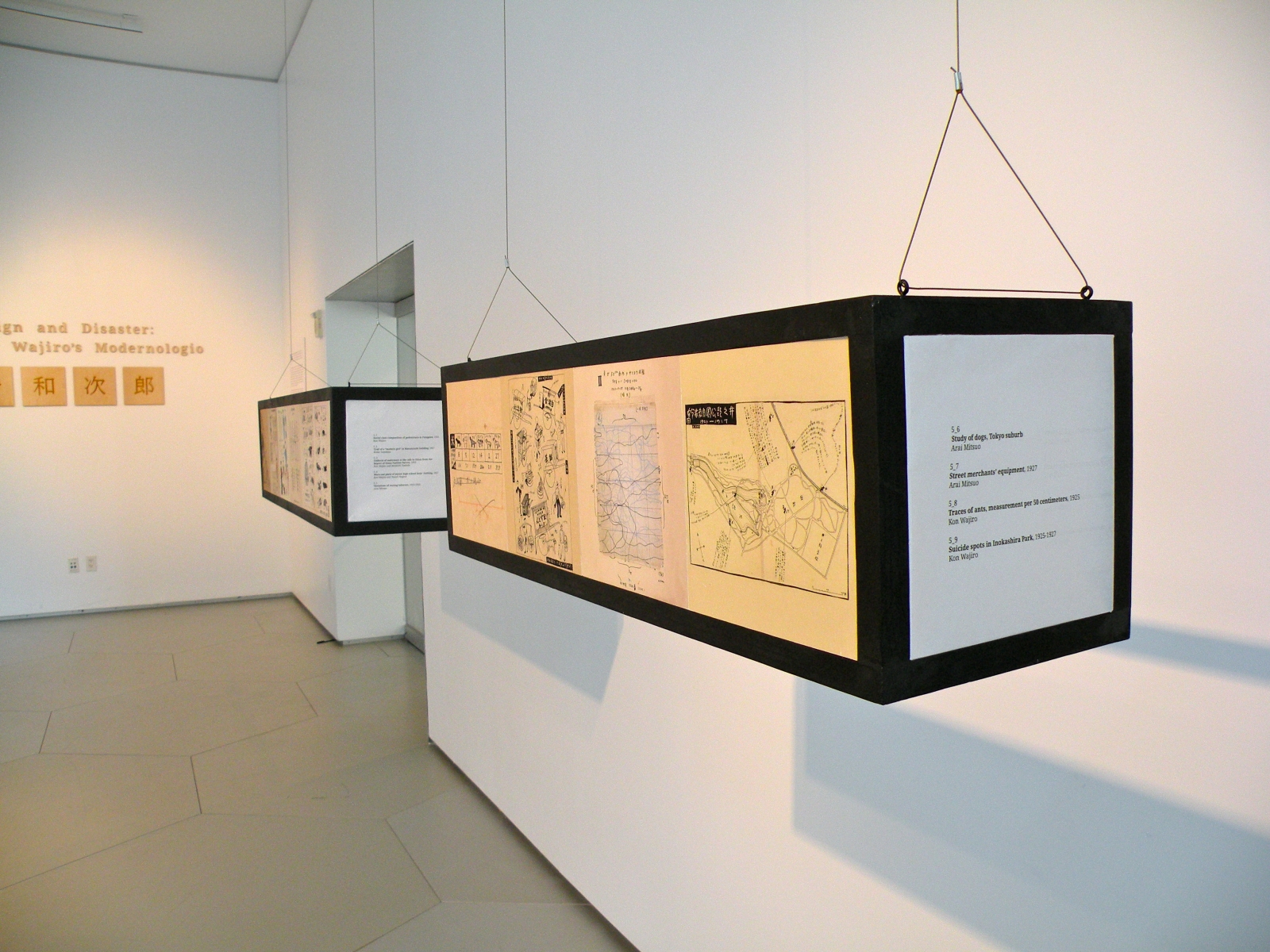

Kon Wajiro’s sketches at the Aronson Gallery, The New School

In the exhibition, the sketches are suspended from the ceiling in rectangular boxes, hung by threads. These delicate wood frames tend to sway as you walk close by and so point to the ephemerality of the show’s subject: a recently destroyed civilization portrayed on equally fragile rice paper.

“Each frame includes drawings of a distinct category: such as interior survey or public realm survey, etc. We wanted to have a simple, minimal presentation with natural materials (wood and rice paper), and to convey the fragility of the original drawings of Kon Wajiro, which are made on rice paper with very fine ink pen,” says Traganou. “Thinking of it in retrospect it looks as if the void (distance between walls and frames, space between the frames) has been given a certain degree of significance, which is also a strong characteristic of traditional Japanese aesthetics.”

In an attempt to look at Kon’s work as a learning tool, students from the New School and Aoyama Gakuin University conducted similar projects that involved extensive fieldwork in Kesennuma, a coastal town of Tohoku that was heavily affected by the earthquake and the tsunami of 2011. (The students’ work is displayed in the hallway outside the gallery.) “As an educator, I found this to be a very useful methodology for spatial analysis. It encourages students to pay attention to users’ practices and to use sketching in a way that does not simply substitute photography. These are analytical drawings, rather than simply snapshots of reality,” explains Traganou.

Design and Disaster: Kon Wajiro’s Modernologio is on display at the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center’s Arnold and Sheila Aronson Galleries at Parsons The New School for Design, until March 27, 2014.

(Sketch on extreme right) Suicide spots in Inokashira park, 1925-1927, Kon Wajiro

Social class composition of pedestrians in Fukagawa, 1925, Kon Wajiro