November 14, 2012

Stick-lets: Bringing Urban Kids Back to Nature

Children are destined to inherit the planet – but they already inhabit our cities. So how can we nurture and protect a child’s infinite capacity for play in the big city? More from Metropolis “Grasshopper Green” Stick-letIn Philadelphia, Stick-lets industrial designer Christina Kazakia has discovered a way to “reconnect urban children to nature with play” […]

Children are destined to inherit the planet – but they already inhabit our cities. So how can we nurture and protect a child’s infinite capacity for play in the big city?

“Grasshopper Green”

Stick-let

In Philadelphia, Stick-lets industrial designer Christina Kazakia has discovered a way to “reconnect urban children to nature with play” combining a transportable, minimalist design with limitless configurations. Her new color silicone kit is currently on display at the Art Alliance on 18th St. in Philadelphia as part of the 2012 Philly Works exhibition.

“What was your favorite childhood memory?” she had initially asked some childhood friends at dinner. Most memories centered around the outdoors where risk taking, mischief, and pent up energy found release. “Nature is nurture,” believes Kazakia who grew up wandering the woods out back from her childhood home in New Jersey. As a professional designer in the making, she wondered how kids today could unplug and engage in the un-tethered play of imagination in nature that she was so fortunate to have experienced.

At The Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Kazakia was asked by her thesis advisors how she could narrow her design focus. “I want to build a tool to build forts,” she quickly responded, launching into eight months of research, prototyping, and documentation that illuminated the “natural imagination” of children. Kazakia says designers too often skip the research, what the user is telling you. She credits critical fieldwork and her supportive classmates of diverse backgrounds for having spurred her pathway to a solution.

Kazakia observed kids at play in the city as they invented elaborate games with simple sticks. If only they had some kind of simple, versatile –something that would spark a kind of wonder, a primal satisfaction, and sense of accomplishment.

Stick-let starter kit

At the Art Alliance show I couldn’t help noticing that Stick-lets bore an uncanny resemblance to bicycle chain components. When I asked it evoked laughter of recognition as Kazakia added, “Maybe I came up with this shape after exploring the release lock system on bikes as a potential mechanism for a stick connector (early prototyping phase).”

Bicycle chain diagram

Attribution: Marcus Roeder

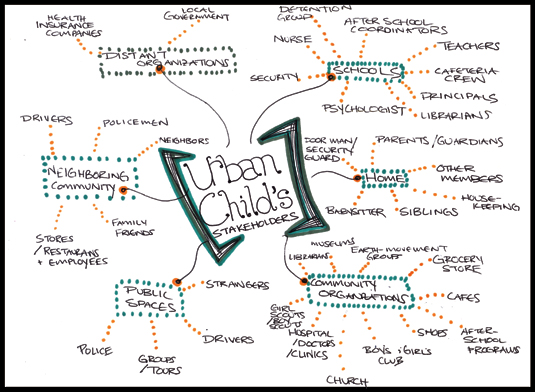

In contrast to rural areas where there is plenty of space to explore, Kazakia says, “City kids need to be able to create a space of their own within a very busy, dense place.”

Kazakia’s research diagram – it takes a city

Scavenging sticks, threading them through rubbery Stick-lets while bouncing ideas off each other brought these kids a startling awareness of their own environment. Do you remember the last time you built a fort?

Thinking about camping and schools, Kazakia contemplates the future of Stick-lets. She has received inquires about adapting Stick-lets for camping shelters. She’d also like to expand product demonstrations to her natural clientele – schoolchildren of all stripes and sizes.

Kazakia invented a colorful connection to the natural imagination of children that could make sense as a creative example for cities learning to do more with less. Sticks are abundant, renewable and free.

Leo Dignam is deputy commissioner of programs for the City of Philadelphia, Parks and Recreation Department, responsible for 150 recreational facilities over 11,000 acres. Access to parks is key to Dignam who cites that “The mayor’s goal is to have every citizen within a ten minute walk of open space areas where kids and adults can walk or exercise. We’re at about 85% of that goal.”

Stepping back to look at the department’s history you have to realize that “In the ’60’s Philadelphia was a model city for park programs. We won several national awards from the National Recreation and Park Association (NRPA),” notes Dignam. What’s changed since then? Parks and Recreation staff was at 1,800 in those days and now it’s at 200, for one thing. “There was a lot of federal money back then,” adds Dignam ruefully.

“We’ve had to learn to adapt,” Dignam rebounds, describing “cluster” strategies where limited resources are distributed more evenly, say from a large neighborhood recreational facility to a constellation of smaller ones. They also partner with schools and universities. Dignam sums up, “We’re much more dependent on volunteers and neighbors now. We’re most successful when you have community involvement.”

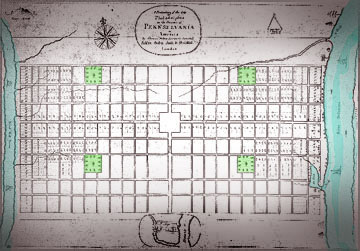

William Penn’s “greene Countrie Towne…which will never be burnt, and always be wholesome” plan for Philadelphia in 1683.

The city hopes to sustain Penn’s “greene”legacy. Perhaps it could be recast with pop-up parks, trellised community gardens or rock climbing walls in abandoned lots. Public Workshop’s TinyWPA, for example, engaging youths to improve public spaces, offers new, collaborative possibilities for Parks and Recreation.

Overall, the emphasis is still on strong programming (may be a higher priority than even new play equipment or maintenance) as the hallmark of the Parks and Recreation Department was in better times.

“Over 250,000 unique individuals participate in over 2,500 programs throughout the year,” Dignam says. “If I had to pick one program that exemplifies excellence in programming it would be our Young Performers Theater Camp. A six-week summer program that we conduct at the Annenberg Center at the University of Pennsylvania. This is part of our Summer Camp Program that serves over 10,000 children.”

The City of Philadelphia may have to struggle to recapture its title as the national leader in parks and recreation. But there is a silver lining. “The best part about my job is being able to see kids’ lives change from our programs,” Dignam says with evident pride and rightful satisfaction.

“Monarch Orange”

Stick-let

Joseph G. Brin is an architect, fine artist and writer based in Philadelphia, PA

Photos:

Christina Kazakia, Stick-lets

Ms. Kazakia’s thesis advisors:

Amy Leidtke, ID; Neal Overstrom, Director of RISD’s Nature Lab; and Beth Mosher, ID