January 21, 2014

Reality Check: Did Women in Architecture Really Gain Ground in 2013?

After the controversies have died down, Sherin Wing asks if 2013 really was the year of the woman.

Was 2013 the year of the woman? There was certainly enough controversy regarding women’s roles in the workplace as well in the domestic arena. The tech sector produced the first salvo with two not dissimilar views on what it takes for women to succeed professionally. Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg and her book advanced the mantra of “leaining in” and popularized the conceit that if women only worked presumably as hard as the author herself—similar to the narrative of “pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps”— then success will certainly follow. Unsurprisingly, backlash ensued which questioned whether Sandberg’s formula could truly be applied to everyone. Then Yahoo CEO and President Marissa Mayer decided to deny women who are mothers the option of telecommuting. In one stroke, she reconfirmed the discriminatory, entrenched opinion that women cannot be truly committed and effective in their professional careers if they are “distracted” by the demands of motherhood while simultaneously establishing once more that the rules don’t apply to the privileged: she issued her decree after having a nursery conveniently built next to her office.

These re-packaged, first-wave feminist discourses are premised on unacknowledged privileges. After all, a woman whose mother holds a PhD and whose parents could afford to send her to Harvard (Sheryl Sandberg) is not representative of most people, nor is a woman who can afford to have a nursery, replete with full-time nannies, built down the hall from the boardroom.

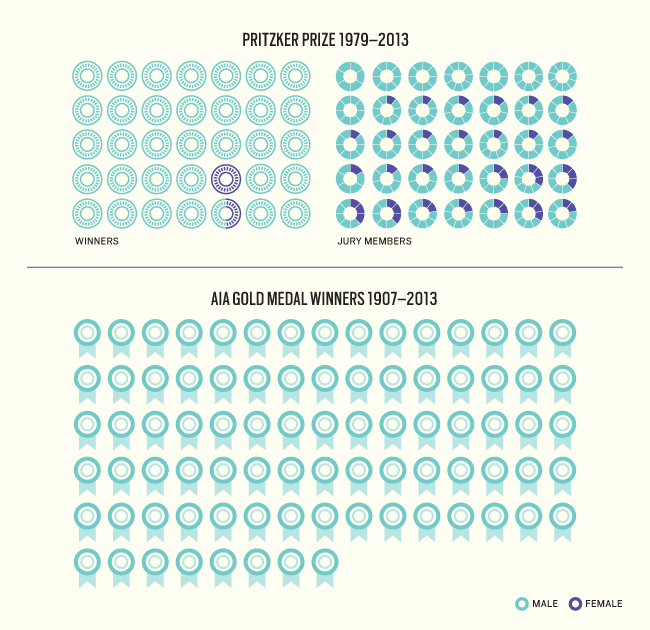

The architecture profession followed these controversies with some of its own. Last June, the Pritzker Architecture Prize committee refused to grant Denise Scott Brown a retroactive award, despite near unanimous support from the profession to pass the motion. In response, a Harvard students group, DesignforEquality, began a petition to right the Pritzker’s erstwhile snub and award Scott Brown a joint Pritzker with her husband, 1991 laureate Robert Venturi. In the wake of all this, the 2014 AIA Gold Medal was awarded to Julia Morgan, an important female architect who also happened to have been dead for fifty-six years. And as if to highlight its own enlightened stance, the British-based Architects’ Journal recently released shortlistlists for their still-young Women in Architecture awards program.

Illustration depicting the gender split in architecture, particularly architectural awards programs. In December, Julia Morgan was named the first female AIA Gold Medal Winner.

Graphic by Dungjai Pungauthaikan

It is certainly true that women architects aren’t afforded the same kind of recognition that their male counterparts are. I have been discussing the issue with frequent Metropolis contributor Guy Horton who has previously explored these issues in articles on Denise Scott Brown and Julia Morgan, one of which I co-wrote. My academic training in gender studies (both men and women), as well as postcolonial studies (the study of colonized peoples in the US and abroad) has fueled my own interest in this area. Specifically, I have been contemplating the issues surrounding women in the context of historical underrepresentation of certain key groups in the architecture profession. How does one approach and frame the discourse?

Missing from all of these narratives and protests is that both professional success and recognition rely on much more than mere personal achievement. The crux of the ongoing debate is that institutions like the AIA and the Pritzker board wield power to institutionalize, and therefore normalize, certain perceptions about the profession. Perceptions such as who deserves recognition, and therefore, who deserves respect, then dictate what emerging architecture professionals should aspire to. And justifiably, many have been worried that these norms exclusively privilege men.

More importantly, institutionalized forms of recognition are predicated on and grounded in one’s social and, equally important, economic status, one’s race, one’s access to education, and even access to food. Repeated studies have shown that there are very real impediments to biological development and achievement, and that not only matters of education, but problems like poverty and access to healthy and affordable food are the most important predictors of future success in school, which foretell professional success. And those issues do not just effect women, but also racial minorities.

Returning to the issue of professional recognition, last December the AIA welcomed its third woman president, Helene Combs Dreiling, FAIA; indeed, all three women are Euro-American. If we use the AIA president’s list as a gauge, one might believe that until 1996, all architects have been Euro-American. In fact, the AIA elected a woman president in 1992, four years before it elected a person of color. All presidents until 1992 have been men and until 1996, all the presidents have been Euro-American.

Similarly, if the Pritzker and AIA Gold Medal awards are really representative of achievement, one might conclude that, until 1966 and 1983 respectively, all architects were Euro-American. Then, in 1966 and 1983, the Pritzker and AIA Gold Medal awards were presented to East Asian foreign nationals, so one would think architects of color are limited only to East Asian foreign nationals and that there are no other people of color practicing architecture. Obviously, this is not true and these titles and awards do not accurately represent the architecture profession’s gender and racial demographics.

This is not an argument for infinite relativism because this is not an issue about individual injured parties. Rather, it is about the power held and generated by institutions to normalize certain modes of behavior, recognition, and ultimately, norms. Until it is acknowledged that those controlling the institutions have an agenda, which reflect themselves and their own values, the symbolic gestures they produce such as awards or positions of power will always remain skewed. It is only when we recognize the power wielded by those who guide those institutions and the values they continue to promote that change will occur.

It’s true these are broad issues and they have far-reaching implications. But that is the responsibility of institutions, large and small, to consider how their decisions and behaviors create an environment that is agile to be on the social and cultural vanguard, rather than focusing solely on design or technology.

Sherin Wing writes on social issues as well as topics in architecture, urbanism, and design. She is a frequent contributor to Archinect, Architect Magazine and other publications. She is also co-author of The Real Architect’s Handbook. She received her PhD from UCLA. Follow Sherin on Twitter at @SherinWing