June 2, 2014

Professional Introvert Susan Cain Rethinks The Open-Plan Office

Teaming up with a best-selling author, Steelcase creates work spaces for those seeking refuge from the constant din of the open-plan office.

Steelcase CEO Jim Keane and author Susan Cain, both self-acknowledged introverts, designed work areas for others like themselves.

Courtesy GS Studios/Steelcase

When asked how his company came to partner with a best-selling author on a product that, unusually, bears her name—the Susan Cain Quiet Spaces, debuting at this year’s Neocon—Steelcase CEO Jim Keane tells a story. “I was at a conference of senior executives, and one of them said, ‘When we have something really important to do, we hold an off-site meeting.’ Just think about that,” he says, sounding amazed. “You spend all this money on your workplace, and when a critical decision needs to be made, you go someplace else. Clearly, there’s something wrong.”

What’s wrong can be summarized in a word: distraction. “It’s people’s top complaint in the office,” says Allan Smith, the company’s global vice president of product marketing. “They can’t find a place to think.” He cites a survey stating that “thirty-one percent of full-time U.S. workers leave their employer’s primary location to get work done.” The culprit, no surprise, is the open-plan layout—that too-extreme response to the Balkanization of employees in offices and cubicles and the desire to encourage collaboration. “You have these two opposing things happening: workers choosing to flee the chaos, and CEOs feeling like building an office culture is the next big thing and wanting people together,” Keane says.

Enter Susan Cain. The author of the 2012 book Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking (Broadway Books), Cain, a former Wall Street lawyer, drew on extensive research—and her own nature—to write about how American culture values extroversion and group engagement over solitude and reflection. “I was driving to a mall on a weekend, and Susan was being interviewed on National Public Radio,” Keane recalls. “I’d never heard of her, but a lot of things she was saying really resonated. At Steelcase, we’re always studying how the office can support different kinds of individuals, and Susan was talking about how, as an introvert, she felt the open-plan workplace was failing people like herself.”

As it happened, Cain was a scheduled speaker at the 2012 TED conference, at which Keane—at the time Steelcase’s president and COO—and then-CEO Jim Hackett were both in attendance. After listening to Cain’s talk—where she observed that “a third to half of the population are introverts” and “solitude is a crucial ingredient, often, to creativity,” lamenting the open-plan workplace in which “we are subject to the constant noise and gaze of our coworkers”—Keane and Hackett sought her out. “Jim shared that he’s an introvert himself, and for years he’d been concerned about the erosion of focus and privacy in the office,” Cain says of the meeting. “I instantly recognized that Steelcase was a kindred spirit.”

All Susan Cain Quiet Spaces images courtesy Steelcase

In fact, Cain and Steelcase were natural collaborators—both hoped to nudge the privacy-versus-communality pendulum back toward the middle, and their investigations had been proceeding on similar tracks. “We were doing a research project on privacy as a universal need,” recalls Vanessa Bradley, the company’s manager of advanced applications. Steelcase was developing five “experience principles” around the issue, which included “strategic anonymity” and well-being, defined as “allowing people to be who they are.” Bradley also describes another project called M1, which was “about supporting the executive as a high-performance athlete in need of moments of rejuvenation.” Cain, meanwhile, was focusing on the negative impact of the open plan on introverts. “You don’t have freedom from interruption,” she says. “There are problems of acoustical privacy. And people actually find it harder to make friends, because you can’t share personal information when everyone can overhear you.” While there was considerable overlap to Cain’s and Steelcase’s findings, Keane says, “There were a lot of non-obvious points she understood that we didn’t. Over time, we began to move toward taking some of the insights she’d had and applying them to our research.”

Around the same time, Cain began Quiet Revolution, a mission-based company focused on empowering introverts in ways that benefit everyone. “We knew a problem we wanted to tackle was the open-plan office,” Cain says. “It was natural to talk to Steelcase because we had this history.” Last fall, Steelcase invited Cain to Grand Rapids, Michigan, to address employees at a speaker series called Curious Minds. Keane took advantage of Cain’s on-campus presence to show off his company’s own spatial diversity. “I showed her that you could have benches and cubicles and enclaves and collaborative spaces, or even work in the cafeteria, and she really got it,” he says.

“What Jim said was, ‘The key is choice,’” Cain says. “I thought, ‘Wow, that’s right.’” The deal began to come together in August, in Chicago. “We got together for an all-day meeting, and the energy was so positive, it was clear that a collaboration would happen.”

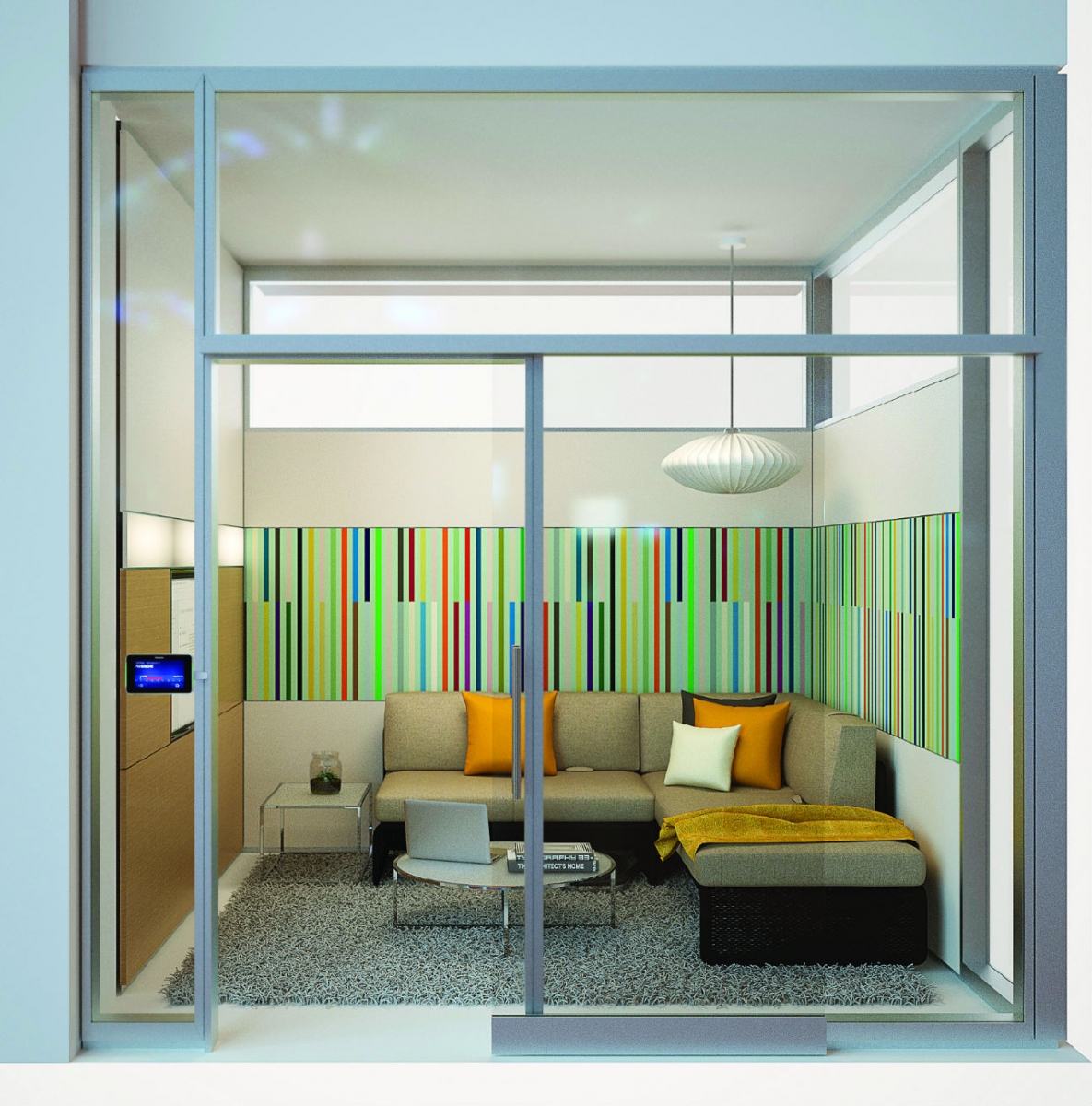

The team’s thinking coalesced around a series of “quiet rooms” geared toward introverts and their heightened sensitivity to stimulation. “We started by creating a list of design principles,” Cain says, adding that the foremost among them was the desire for “a real sense of privacy— where you can’t be seen, can’t be heard, and you can do your own thing.” She stressed the importance, to the introvert, of “psychological comfort”—the need to not be on display, visually or acoustically distracted, or overheard. At the same time, Keane points out, “Introverts often want to be with other people, but in a more focused, less gregarious way. So we wanted spaces that were about that kind of collaboration.” All agreed there should be rooms promoting rejuvenation as well as work. “And I wanted them to feel cozy, intimate—to send design signals different from the ones you get in corporate life,” Cain says.

Interestingly, Steelcase wasn’t concerned about creating a too narrowly focused product. “When designers aim at a particular customer—people they’ve met and empathize with, and are connected to on a human level— the point of view gets very strong, and you attract people who weren’t in your target market,” Keane says. “Everyone is an introvert sometimes, and if it’s great for introverts, it’s going to be great for everyone.”

The outcome is a palette of five rooms—four of which will be unveiled at NeoCon—that fall into two categories: focused work, and rest and rejuvenation. Across the board, specificity is key. “Unlike the more traditional ‘neutral place setting,’ we decided—based on what Susan was telling us—to make these rooms highly prescriptive,” Bradley explains. “We wanted people to walk in and immediately understand how they were meant to be used.”

That said, all five share certain qualities. Foremost is their construction: Each is built from Vertical Intelligent Architecture (VIA), a Steelcase glass wall product that ensures, according to Bradley, 100 percent acoustical privacy. “Moreover, VIA not only routes power and data, but becomes a conduit for integrated technology, such as video displays,” she explains. Each room offers users the ability to fine-tune lighting levels and create total or partial opacity, with wood, fabric coverings, or vinyl applied to the glass. The furniture, all drawn from existing Steelcase product lines (including the company’s premium furniture brand, Coalesse), represents an effort “to bring in comfortable, softer elements and natural materials—more of a home-office aesthetic,” Smith says.

The individual-focus room, called Flow, is meant to support “absorbed, heads-down work,” as Bradley calls it. The design created a cockpit-like feel with a traditional task-height surface and upright chair posture, and inserted a 27-inch monitor into the wall above the desk. Dimmable lighting, perfect silence, and visual opacity support the immersive experience, and—though it’s clearly a work space— the user’s ability to customize finishes and fabrics “makes it a warm, residential environment,” Bradley believes. Similarly, Mind Share, the two-person room designed for “deep-focus, generative dyadic work,” features two office chairs and a slightly larger task table within a comfortable, cocoon-like setting.

The three rooms dedicated to rest and rejuvenation are more varied. With its built-in speakers, 42-inch visual display, and comfortable lounge chair, Studio supports “shallow focus—you can go in with your iPad and check email—or passive respite, the opportunity to take a personal moment,” says Bradley. There’s also room for a yoga mat, so users can engage in an activity that re-grounds and refreshes them. Be Me—what Smith calls the “cry room”—is a single-user space that lets people decompress and recover between meetings, or even just sleep off jet lag.

The room that Cain was really passionate about, according to Bradley, was the Green Room, notable for its L-shaped sectional sofa. “I wanted people to talk to each other in an intimate way that you don’t ordinarily associate with corporate life,” Cain explains. Like a corner booth in a bar, the L shape at once affords separation and encourages connection. And it speaks to an introvert-specific need that is also universal. “Creating a culture of permission is important for introverts,” Bradley says. “By putting this type of space in your office, you’re sending a signal that it’s okay to use it in any way you’d like.”

As for how the Quiet Spaces get deployed, Bradley says, “We have a group of field-based application designers, and they’ll work with customers to determine what’s the right fit.” Cain doesn’t believe the idea will catch on, however, if a company opts for just one or two rooms: “It’s only going to work if there’s enough of them that people can choose moment by moment.”

Whatever the configuration, it’s an idea—perhaps even a radical one—whose time has come. “It’s the first time I’ve seen anyone in our industry go to market with complete applications that are purpose-built based on insights about a cohort,” Smith says. Cain’s take on it, not surprisingly, is more introverted. “I used to have fish when I was growing up, and there were rocks in the aquarium,” she says. “Most of the time, the fish would swim around, but ultimately retreat to their own rocks. People are the same. We want to swim in the open—and then we want to come back to our rocks.”