September 30, 2013

A Sustainable Architecture Has Yet to Be Realized, Says Bob Berkebile

The next building environment today: sustainable architecture is yet to be realized

The green building movement doesn’t have one founder—it has several. One of them, without question, is Bob Berkebile, a founding principal at BNIM in Kansas City. In the 1990s Berkebile was part of the small circle of architects, designers and businesspeople who helped create the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED program . He served as a delegate at the Earth Summit in Rio. Later, he took certification a step further and created (with Jason McLennan) the Living Building Challenge, a vigorous standard that exceeds LEED Platinum and serves as both aspiration and model.

My conversation with Berkebile is the second installment in The Next Building Environment Today series, a collaboration between Metropolis magazine and Architecture 2030. Each month I interview an internationally recognized leader in the green building movement. Here Berkebile talks about the recent Bank of America controversy, his new concept of Urban Acupuncture, early efforts in China, and the Architecture 2030 Palette/

Martin C. Pedersen: You followed the controversy surrounding the Bank of America building in New York. What was your take on the New Republic article accusing the building of being an energy hog?

Bob Berkebile: I don’t know all the facts, but the early responses suggest that it’s being compared unfavorably to the Empire State, but that’s still relatively empty and Bank of America is full. Again, I don’t know the facts. What I do know is, when a system is undergoing change—and I would argue that LEED has created more change in our industry than any other single thing in my professional career—when that amount of change occurs, there are always pushbacks. Several months ago US Today did two feature articles, saying that LEED is broken. When you look at the overall energy numbers, buildings have improved significantly. But the LEED system, as it has matured, is a like a natural system. Are you familiar with the S-curve that defines the vitality over time of a natural system?

Bob Berkebile

Courtesy BNIM

MCP: No.

BB: It’s a very interesting. Let’s take, for example, an oak forest. You have an X- and Y-axis. The vertical is vitality; the horizontal is time. You plant an acorn, and initially that s-curve is below the line, because it’s taking nutrients, taking resources from the soil, water and sun, and not producing anything. As it becomes a tree, then it starts being productive. It’s sequestering carbon, managing water, sharing nutrients with other plant systems. As time goes forward that S turns up and becomes a steep incline as it increases its contribution and vitality. Then as the forest matures and gets to the climax phase, the line starts bending down again. So the graph looks like an S on its side. Then what happens in a natural system is something modifies it, like fire, and that regenerates the forest, and restarts the S-curve. That might be where we’re at in the green building movement.

MCP: The one thing the New Republic story underscored was the importance of post-occupancy studies, especially as they relate to energy.

BB: One of the flaws—and there are a number of them in the LEED system—is that it does not require post-occupancy evaluation. It encourages it, but it doesn’t require it. What does require post-occupancy evaluation is the Living Building Challenge. We started working on that idea, as we were also developing the LEED system in the mid-90s, because it became obvious early on that a volunteer program, developed by consensus, wouldn’t get us to the level of performance that we wanted. That’s when Jason McLennan and I started thinking about the Living Building Challenge. That does require a one-year after the fact third-party evaluation.

Courtesy Make It Right’s Kansas City project

MCP: That’s the direction the USGBC should go in, especially for Platinum certification. Do you agree?

BB: My hope was that by now we would drop Certified and replace it at the top with the Living Building Challenge. It would be Silver, Gold, Platinum, and Living Building. I would argue that Certified is current standard practice. The only way you advance the system is by continuing to redefine it. And what that looks like at the USGBC is still an open question. When it became obvious that the Living Building Challenge wouldn’t be that next step, they hired us as consultants to rethink what it could be. We developed a concept called Generous Design, but they rebranded it ReGen, for regenerative. That’s the path they’re on, but that tool hasn’t been funded.

MCP: Why not?

BB: They’re reluctant to invest the money in the software for creating the program. What we initially concluded was: we didn’t need another ratings system. We needed help in thinking differently. ReGen is conceived as a software program that creates a global dialogue of discovery, introducing designers, developers, building owners, bankers, to a much bigger picture of what’s possible. It provides them direct contact with best practices, so that they can make the leap to high performance and Living Buildings.

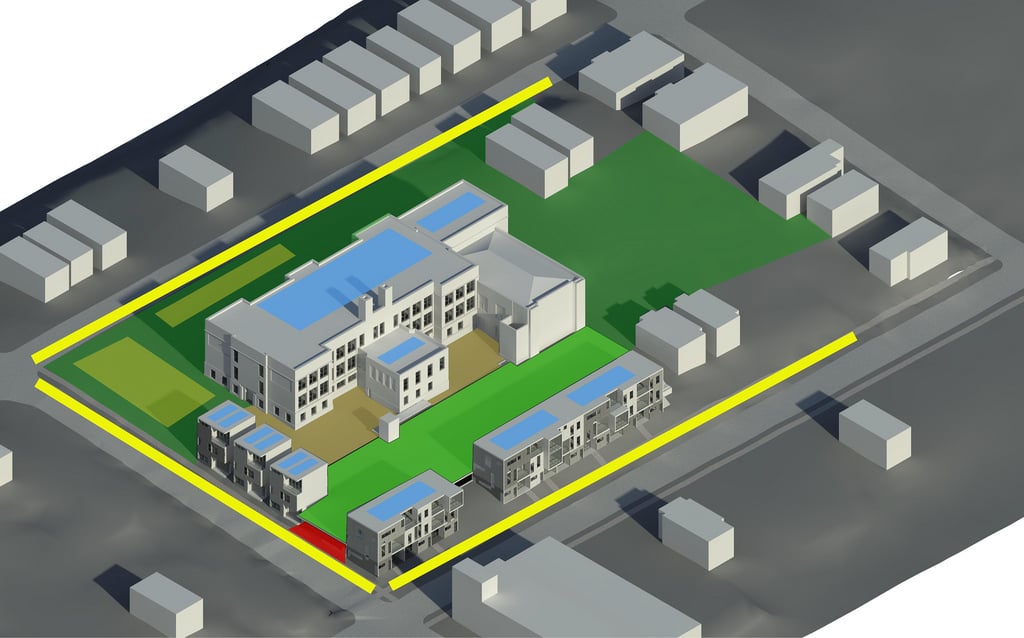

MCP: Your firm is working on a new concept called “urban acupuncture.” Tell us about that.

BB: About a year ago we started a development company that has been focused on this idea. It’s an evolving concept and we’re learning as we go. Today’s definition is: it’s a strategic investment of leadership, design and capital, at an important place, at a critical time, to stimulate transformative, positive change. We have an urban acupuncture project under construction, which our development company didn’t do.

Courtesy Make It Right’s Kansas City project

MCP: That’s the Make It Right project in Kansas City? BNIM is heavily involved with that.

BB: Yes. We did the early conceptual work. We also did the design work, and recruited the developer, and brought in Make It Right to help us with the philanthropy and bring it to its full potential. We’re working in a neighborhood that Congressman Cleaver and I refer to as the “green impact zone,” and the Kansas City Star calls the “killing zip code.” Roughly half of the houses in this neighborhood were lost to fire or demolition over the last few decades. The school in the middle of the neighborhood had been empty for fifteen years. In working with the neighborhood, we concluded with them that the greatest opportunity would be to acquire and repurpose that school, because it had been the center of the community. We wanted to find a new use that would add human capacity to that neighborhood. What we’ve done—it’s now under construction and should be occupied later this year—is convert that school to housing, a clinic, a computer lab, and a community center. On the rest of the site, we’ll build some new attached townhomes, and they will be surrounded by urban gardens.

MCP: In our first conversation with Peter Calthorpe, we talked a lot about China. I’d like to get your impressions. On your website you write, “The mode being used to develop these ’Cities of Tomorrow’ is based on the fundamentally obsolete thinking of yesterday.” Explain what you mean by that.

BB: First of all, I should disclose that around 2000 I served on the Department of Energy’s expert team to China. We were working on relocating people out of what is now the lake that was created by the Three Gorges Dam. I had trouble with the concept of the dam, to begin with, and the more I learned about it…

Courtesy Make It Right’s Kansas City project

MCP: The less you liked it.

BB: Exactly. China sent a delegation to the states. We spent about a week at the federal center in Denver, working with them. Our mission was to help them create a pilot, sustainable community for the displaced people. We explored some great ideas. We gave them a list of things that we needed before we made the trip there. And when they returned home, we just couldn’t get the information—the land surveys, the hydrology, all that. So I called a meeting of our team and said that if we don’t get this material in the next week, we shouldn’t make the trip. Ultimately, we did get the material on the last day of the second deadline. But when we got it, it was obvious that the site they’d selected was in a floodplain. I called another meeting. “Building in harm’s way is not sustainable,” I said. “Our whole mission was to create a sustainable community. We can’t do it.” The team facilitator, who was not part of the design team but was brought in to manage the project, said, “Bob, you can’t say that to them. That’s not culturally acceptable.” I said, “Well, nature trumps culture.”

There was a lot of back and forth, and eventually I resigned from the team. The Chinese were wonderful people, but no matter what we showed them in the way of evidence about high performance, integrated planning and design, their pushback was always, “Wait a minute, Bob, all we want is what you’ve had for the past fifty years. We’re just doing what you’ve been doing.” I’d say, “And we’re just waking up to the fact that these were ill conceived ideas!” That wasn’t a compelling argument for them. On the flight home, I determined that what our firm should be doing is creating models here that are worthy of replication, rather than being over there and trying to convince them that what we’ve been doing for the past half century was wrong.

MCP: It’s now been thirteen years. If you had an opportunity to re-engage, would you?

BB: We’ve had some opportunities, but so far we’ve declined. But to be candid, if given the right circumstance, we probably would re-engage, because they’re building New York there every few weeks.

MCP: They’re too important.

BB: Yes. We have to realize that, and do everything we can. Now there are good things happening in China. Some of the obsolete infrastructure that we’re burdened with, they skipped over. In terms of communications, they skipped over the hard wire stuff. In transportation, they’re on the verge of creating a connected, high-speed rail system, and not investing as much in highways. That’s still not a foregone conclusion, but they’re on the brink of some interesting breakthroughs.

MCP: We just have to get them to stop burning coal.

BB: Ironically, one of my closest friends was the senior vice president of GE and lived in Hong Kong for a long time, and he was selling, on the average, a coal plant a week in the Pacific Rim. It’s dynamic. There are a lot of forces at work, and it’s why I’m convinced that what’s required now is that each of us do something as beautiful, as engaging, as pedagogical as humanly possible, and then allow social media and other communication techniques to spread the word.

Courtesy Make It Right’s Kansas City project

MCP: You’ve worked with a number of communities, following disasters, such as Greensburg, Kansas. Talk about how that work relates to how we’ll have to plan in the future. Clearly, the climate is clearly changing.

BB: First of all, relative to climate, the National Science Foundation took me to Antarctica in 1992. I was part of a research team. The U.S. had been cited by Greenpeace for our environmental misbehavior in Antarctica. So seven of us went down to look at it and see if we could come up with a quick strategy for how we might turn that whole pattern around. It was there that I first got a deep dive into climate, and I came back on fire. What I discovered was, we could dramatically reduce their carbon footprint and the efficiency, health and productivity of the employees there without building new stuff. By retrofitting what was there and repurposing a lot of things, we could accomplish transformative changes. So flying back, which is almost a full day flight, I had a lot of time to think about it, and I realized that the opportunities here at home were far greater than there. It was just easier to identify there, because it was so isolated and harsh. Here the systems are so integral and multi-generational and complex, it’s harder to see. But clearly we had a much larger opportunity, at a much lower cost, to create the same transformation.

That was a huge revelation to me, which started informing our work. And every forecast they made while I was in Antarctica about the environment, in terms of warming, ice melt, have all been exceeded by reality. When I came home, I started sharing what I’d learned, and my colleagues said: “Bob, we love you, but those people are crazy. They have very large computer models, but no real data.” But now we have ice samples that go back hundreds of thousands of years. We have samples from outer space, from the bottom of the ocean. In each case, when they put real data in, the forecast got worse. The debate is over. It’s a question now of how do we respond to it appropriately.

MCP: Have you had a chance to look at Architecture 2030’s “2030 Palette”?

BB: I like the idea a lot. My colleagues here are planning to be part of the pilot, to really roll this out so that others use it.

MCP: What I like about it is, it’s written and designed in an accessible way. It explains complex things in simple terms.

BB: That’s exactly what’s unique about it, and it’s exactly what’s required right now. It’s just like the early conversations in Greensburg, Kansas, after the tornado. If we’d given them the usual jargon there would have been no exploration. But because we were listening more than preaching, together we created a way to look at everything differently. The 2030 Palette invites people into the same kind of exploration.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Navigating the Path to Net Zero